One evening in March of 1998, Elliott Smith stepped out onstage in the Shrine Auditorium, with Jack Nicholson, James Cameron, Madonna, Aaliyah, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Denzel Washington, and 57 million other people watching him.

Smith, 29 at the time, had spent most of the '90s working odd jobs around Portland and playing with Heatmiser, an indie rock band who'd eventually found an OK-sized audience. He'd also been recording fragile and quiet and beautiful acoustic music on his own. It took a while, but that music built up a reverent, rapturous cult fanbase, and Smith's solo music had come to outshine his work with Heatmiser, who'd broken up in 1996.

By 1997, Smith had released three solo albums on Kill Rock Stars, and a fellow fringey Portland artist had taken notice. Gus Van Sant, the indie film hero, had come on board to direct Good Will Hunting, a movie written by the upstart actors Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. The movie was, of course, monstrously popular, and it led to Van Sant getting his own rare little moment of mainstream recognition. Van Sant had gotten Smith to contribute a few songs to that movie, and one of those songs, "Miss Misery," had gotten a flukey Oscar nomination, part of the wave of recognition for Good Will Hunting.

On that Sunday night, the orchestra was already playing by the time Smith walked onstage -- white suit, messy hair, acoustic guitar. Smith stood alone at center stage, eyes downcast, and sang an abbreviated version of "Miss Misery." The orchestral embellishments, which sounded nothing like anything that was on Smith's original, still sounded pretty nice. Smith's voice, always soft and whispery, started out tremulous, almost radiating nerves. But Smith seemed to pick up at least a bit of confidence as he went. The orchestra's tin-whistle flute somehow drew lines between "Miss Misery" and the Titanic soundtrack. And moments after Smith finished, Céline Dion stepped onstage amidst clouds of dry ice, the stage behind her made to look like a ship's ballroom. She belted out "My Heart Will Go On," the song that was always fated to win that year's Best Original Song Oscar. And then Smith, Dion, and fellow performer Trisha Yearwood linked hands and bowed. For years afterward, Smith talked about how kind and generous Dion was, how she'd helped calm him down.

In the 20 years since that moment, the Oscars have played host to plenty of indie and indie-adjacent performers: Aimee Mann in 2000, Björk in 2001, the Swell Season in 2008, Florence Welch in 2010, Karen O and Ezra Koenig in 2014, Tegan And Sara with the Lonely Island in 2015. Just this past year, Sufjan Stevens performed, with St. Vincent and Moses Sumney backing him up. We're used to seeing stuff like this. But in 1998, the internet was in its infancy, and word-of-mouth cult stars like Elliott Smith found their audience through actual word of mouth -- through local alt-weekly reviews, or through tapes passed from one friend to another. (In high school, I knew a girl who was absolutely besotted with Smith's Either/Or, who played it all the time. I wasn't ready for any quiet acoustic music at that point in my life, but that's how I first heard of Elliott Smith. Some version of that is how everyone first heard of Elliott Smith before Good Will Hunting. It's probably how Gus Van Sant first heard of him.)

And this was the Oscars, back when the ceremony still recognized massively popular movies, when it was arguably at the peak of its cultural impact. (This year's Oscars had less than half the viewership of the 1998 show.) To see Elliott Smith performing on a show like that was like... well, there's really no parallel that even comes close. It wasn't like anything. It was like seeing Elliott Smith perform at the 1998 Oscars.

So Elliott Smith signed to a major label. It had to happen. It was preordained. You couldn't perform at the Titanic Oscars and keep putting out records on Kill Rock Stars. That kind of thing just didn't happen in the '90s. The funny thing was that when Smith signed with DreamWorks, shortly after those Oscars, it was his second time on a major. Heatmiser had done a deal with Virgin during the dying days of the post-Nirvana underground-rock gold rush. But they'd broken up before the release of Mic City Sons, their one major-label album, and Virgin ended up just barely releasing the album through the pseudo-indie Caroline. It was for the best. It's not like Mic City Sons was going to suddenly transform Heatmiser into global icons. Dozens, maybe hundreds, of major-label records like that came out in the '90s -- onetime alt-rock hopes who were soon forgotten and banished to cutout-bin purgatory. The people at Virgin still had Smith under some kind of contract; maybe they just hadn't noticed that he'd been putting out indie records this whole time. DreamWorks had to buy that contract out. And in his second major-label go-around, Smith found himself in a very different position. For once, people actually wanted to hear him.

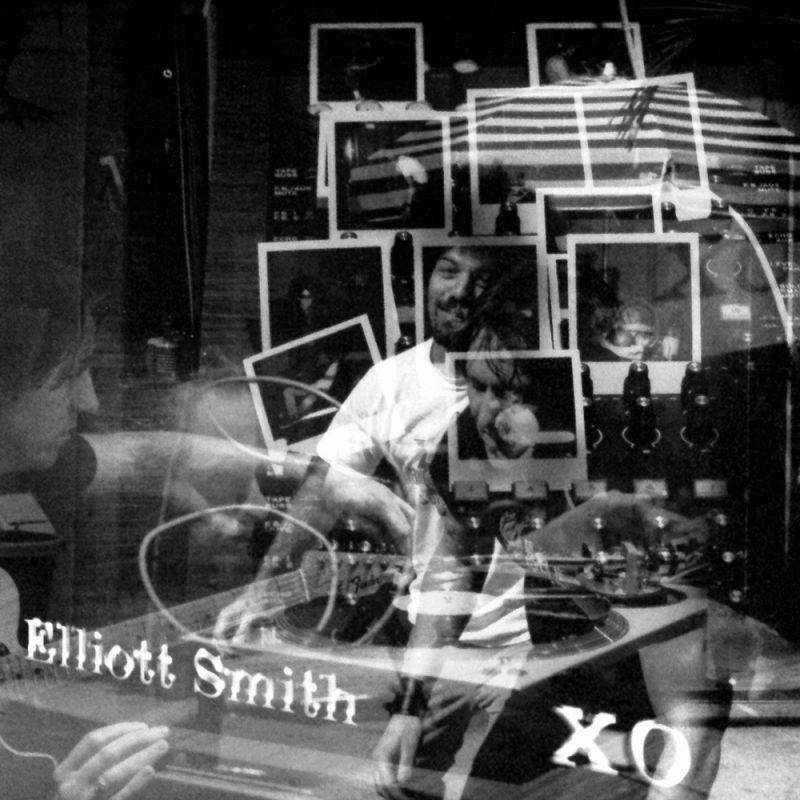

What happened next is fascinating. Smith's solo music had already been evolving from the scratchy and lo-fi four-track recordings of 1994's Roman Candle. He layered his guitars. He added piano. But on XO, the album that will turn 20 on Saturday, Smith's songcraft exploded. Working with Beck collaborators Rob Schnapf and Tom Rothrock, the same pair who'd co-produced Either/Or with him, Smith took inspiration from the lush singer-songwriter music of the '70s. And he built an orchestral pop masterwork. After years of making hushed, fragile music, Smith was suddenly bursting with melody. XO has sounds shooting off in every direction -- electric pianos, mandolins, melodicas, horns, strings, Chamberlins, pillowy multi-tracked backing vocals. Jon Brion, the genius film-composer who was still developing his own sparkling studio aesthetic, is all over the album. It's a quantum leap into some idea of pop music from an artist who had always seemed fully inwardly directed.

Of course, Smith still was inwardly directed. He could stuff all these new sounds onto XO, but he couldn't change his own fluttery and delicate voice. And he was still an almost painfully intimate songwriter. "Sweet Adeline," the album's opening track, is a beautiful example of all the things going on on XO. It opens with a spindly guitar and a half-murmured vocal, the sound of a kid in the back of church who's trying not to be heard. All of a sudden, things surge upward and outward. Guitars and pianos and backing vocals flare up like roman candles, an adjustment so sharp and total that it reminds me of the moment in The Wizard Of Oz where black-and-white turns to color. It's so musically overwhelming, in fact, that you might not notice, at first, the raw-ass substance of what Smith is singing: "Waiting for sedation to disconnect my head / Or any situation where I'm better off than dead." Once that sinks in, you become aware that you are hearing a man who is going through some shit.

And he was. Around the same time that he signed to DreamWorks, Smith attempted suicide, getting drunk and jumping off of a cliff in North Carolina. He'd been fighting some serious demons, dealing with alcoholism and with the painful repressed memories of childhood sexual abuse. Aesthetically, XO is a work of deep and nurturing beauty, all its layers arranged into sweeping and majestic vistas. Lyrically, it is raw and wounded to a startling degree.

There are moments of depression and desperation on XO that will spin your whole head around two decades later, especially when you consider Smith's ultimate fate. There's a grim evocation of staying awake in the middle of the night, attuned only to the thoughts you don't want to be thinking: "I got static in my head / The reflected sound of everything / Tried to go to where it led / But it didn't lead to anything." There's deep isolation: "The safety of a pitch-black mind / An airless cell that blocks the day." There's simple inadequacy: "I'm not half of what I wish I was." There's even the feeling that the people in your life, the ones who are trying to help you and keep you sober and happy, don't actually know the first thing about you: "It's a chemical embrace that kicks you in the head / To a pure synthetic sympathy that infuriates you totally / And a quiet lie that makes you want to scream and shout... Fuckin' oughta stay the hell away from things you know nothing about."

There are relationships on XO, but they're fraught and disconnected -- the stormy dysfunctional partnership on "Bottle Up And Explode," the drunken commiseration on "Baby Britain." "Amity," a charged-up rocker about being excited to meet up with someone in New York, is a total outlier, and even that has the line "God don't make no junk / But it's plain to see that he still made me." "Waltz #2," quite possibly the greatest song Smith ever wrote, is a gorgeous and harrowing character study of his own mother, someone who folded completely inward to get through an abusive and neglectful relationship. The album ends the only way it could, with Smith beatifically cooing, "My feelings never change a bit / I always feel like shit," the music doing the alchemical work of transforming ugly sentiment into shattering beauty.

They'd both grow -- the beauty and the depression. Smith's next album, his final completed one, was 2000's Figure 8, a work of dizzily lush power-pop that was sonic worlds away from his indie work. But Smith got himself hooked on heroin around the same time, and his paranoiac and self-destructive tendencies got worse. And in 2003, five years after releasing XO, Smith died from two stab wounds to the chest -- presumably a suicide, though there are still questions.

Smith made five albums in his solo career, and they're all staggeringly beautiful in one way or another. Maybe XO is the transitional album, the moment where he was switching over from being an unknown and self-reflexive acoustic indie guy to a full-on studio-pop auteur. Even if that's the case, though, the sound of XO is warm and intuitive and fully-formed. Smith clearly already had some idea of how he might sound if he had the resources. And once he got those resources, he created that sound with stunning clarity.

And XO remains my favorite Smith album -- partly because it's great, obviously, but also partly because it was the one that hit me in the exact right stage of my life. I'd been at college for a week or two when I bought the XO CD from the record store a block away from campus. That was a rough stage of my life, an uncertain transition to a city that I didn't know and to a social scene that didn't make a lot of sense to me. And I spent a lot of nights in my dorm room with XO on repeat, absorbing all that beauty and all that sadness. Twenty years later, they're both as tangible as they ever were.