Mystique is a funny thing. When Belle And Sebastian first found their audience, a few years after they'd honed their sound in Glaswegian classrooms and practice spaces, the mystique was a huge selling point. Here was this group of mysterious Scottish people who made impossibly pretty folk-pop songs about being cripplingly shy and about looking for connection anyway. And we didn't know anything about them. They wouldn't play live shows or do interviews or pose for photos. They'd emerged fully formed from nowhere, and they spent so much time creating their own private world that they kept the rest of the world at arm's length. Eventually, the rest of the world was going to come barging in.

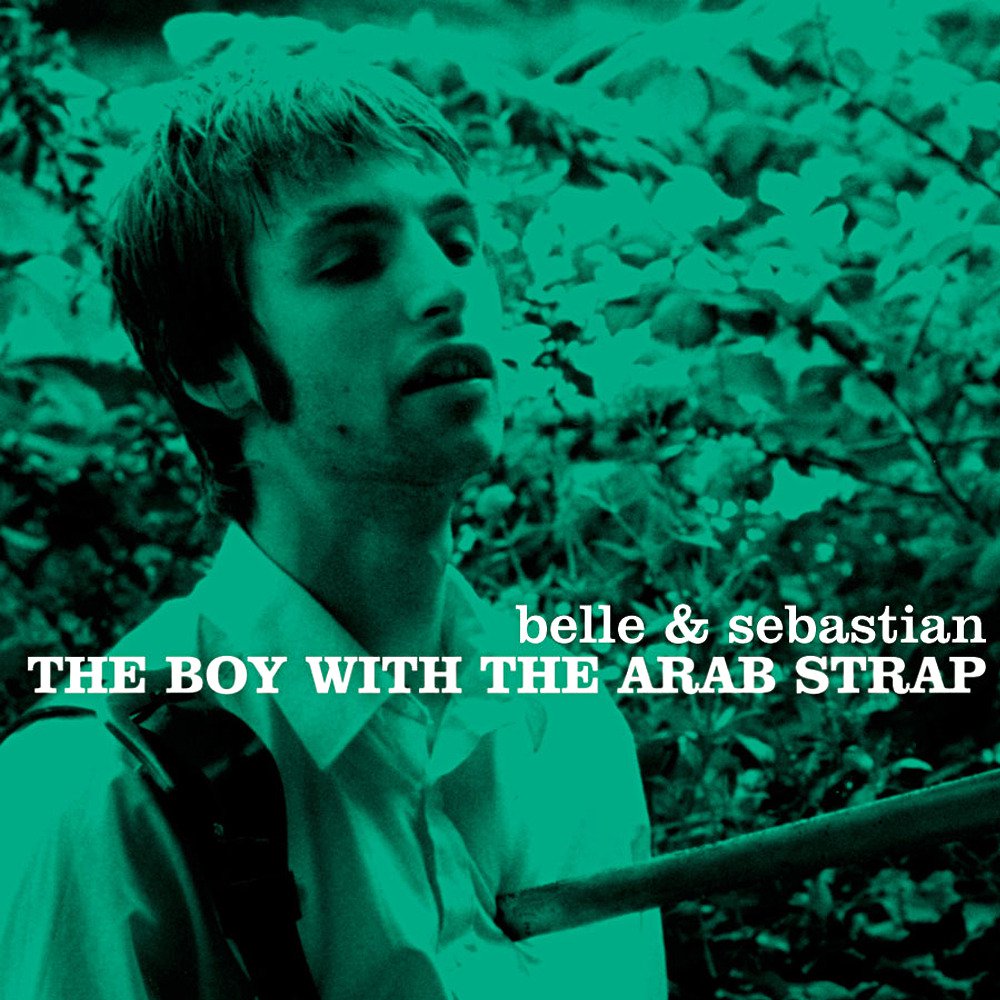

The Boy With The Arab Strap, the third Belle And Sebastian album, is the first album that the band made when they knew people were listening. If You're Feeling Sinister, their quiet masterpiece of a sophomore album, had found international distribution and turned them into global cult stars. They'd made their first halting, awkward attempts at playing live shows. A few of their songs actually charted in the UK, which must've been baffling for everyone involved. They'd made a bunch of short EPs, keeping their chops up but also running through the stored-up reserve of songs that Stuart Murdoch had written while suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome. But Arab Strap was the coming-out party, if an album that insular can be called a party.

It's also the moment where the band started to democratize itself. Stuart Murdoch, the mysterious mastermind who'd written all of the band's songs, started to let his bandmates take over. This really bothered some people. But even the non-Murdoch songs on The Boy With The Arab Strap completely fit within the group's aesthetic, even bassist Stuart David's lightly dazed spoken-word soundtrack-jazz narrative epiphany "A Spaceboy Dream." (Pretty soon, David would leave the band so that he could make nothing but songs like that with his Looper project, which was pretty good for a while.)

There are two songs on The Boy With The Arab Strap where we're forced to contemplate how weird it must've been for the members of Belle And Sebastian to venture out into the world, and neither of those songs came from Murdoch. Instead, they both belong to guitarist Stevie Jackson. On "Seymour Stein," the band meets a music-business legend, the guy who signed the Ramones and the Talking Heads and Madonna. Stein is offering them "promises of fame, promises of fortune," but Jackson is barely listening. Instead, he's in a fog, thinking about some girl he's missing. When we do hear from Stein, he's offering up record-biz chatter that seems alien and self-parodic. (One of the Belles "reminded you of Johnny, before he went Electronic.") It might as well be a song about meeting a ghost, or an antelope. It's pretty interesting, but you don't really have anything to talk about.

Jackson's other contribution is "Chickfactor," named after a New York indie rock zine that stopped publishing in 2002. On that song, Jackson gets interviewed by a girl from the zine in question -- apparently the band had relaxed the no-interviews policy by then -- and finds himself crushing on her while also thinking about the girl he left back home. The girl from the zine is showing him what it's like to be young and cool in New York, and he's into it, but he's also slightly baffled. He seems more starstruck to be talking to someone from a zine than she is to be talking to him. (We never actually hear from her, so we never find out for sure.) You haven't necessarily hit the big time if you're talking to someone from a zine, but that's how Jackson feels. It's all new to him.

Most of the way through, The Boy With The Arab Strap is a typically gorgeous early Belle And Sebastian album. When it came out in 1998 -- 20 years ago, as of today -- it felt instantly familiar. Murdoch's songs, uniformly excellent, built on the same plush self-deprecation that he'd used on If You're Feeling Sinister. It never felt as new or as exciting as that album, but a song like "Sleep The Clock Around" captured the spirit of the band about as well as it could be captured. There were embellishments -- horns, bagpipes, Motown-style string sections. On a few isolated moments, like the Hammond organ intro from the title track, they almost sounded soulful. But Belle And Sebastian were built for embellishments, so those tweaks never hurt the band's appeal. And honestly, it's remarkable that a group this shy could find a way to keep its spirit intact when the world started paying attention. It wouldn't last.

Belle And Sebastian are still around, of course. They still make good records, though I don't think anything they've ever done has touched those first three albums. (Or maybe those first four; I keep a warm spot in my heart for Fold Your Hands Child, You Walk Like A Peasant.) They've become a dependable festival act. Stuart David left in 2000. Isobel Campbell, whose "Is It Wicked Not To Care?" might be the best song on The Boy With The Arab Strap, followed two years later. Stevie Jackson stayed in the band. They charted a few more times. They won a Brit Award. They showed up on Top Of The Pops. Stuart Murdoch made a movie. The band's music got slicker and sillier, often verging into showtune territory.

Today, Belle And Sebastian are a fine indie rock legacy act, a nice band to have around. But they've lost something. That tremulous warmth, that sense that they'd found a way to take social anxiety and make it sound glamorous, is gone. Really, it started to slip away right after The Boy With The Arab Strap. Maybe it wasn't sustainable. Maybe that wilting-wallflower thing is a persona you can't keep up when you've been in the public eye for long enough. Or maybe I'm a mark for mystique, and the problem is me. But for those of us who were still young and awkward when we first heard it, The Boy With The Arab Strap continues to work as an aural time machine, a way to immediately melt back into that era when that level of purity was something worth fetishizing. There was romance in that. And Belle And Sebastian, for a while there, were really great romantics.