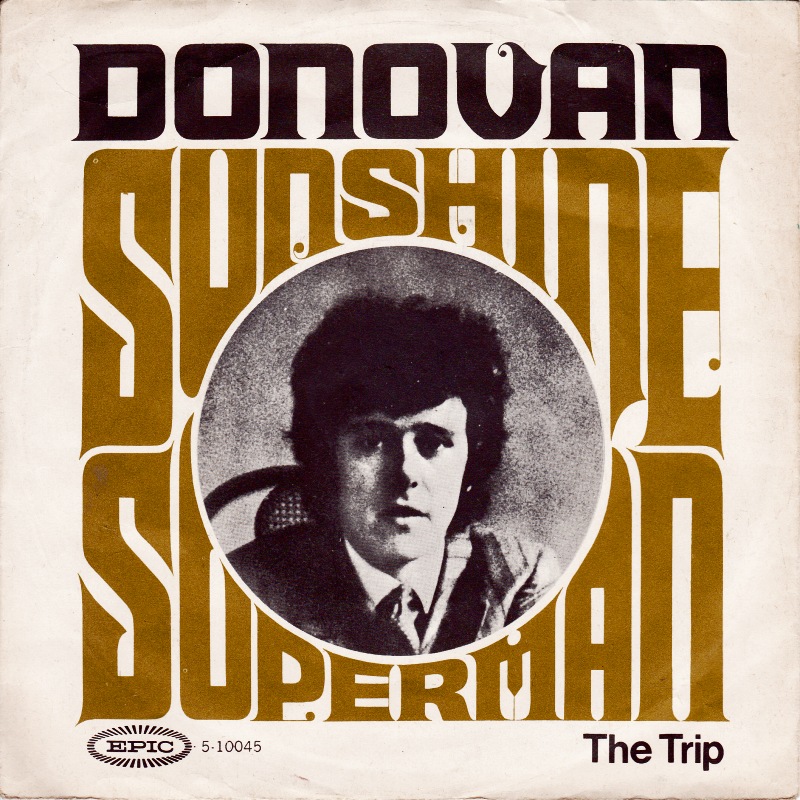

September 3, 1966

- STAYED AT #1:1 Week

In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

There's a famous 1965 press conference where a whole horde of slightly befuddled reporters (and, for whatever reason, Allen Ginsberg) sits in front of Bob Dylan, firing one ridiculous question after another at him: "Do you ever paint or sculpt?," that kind of thing. Dylan, smirking at the absurdity of it all, answers all the questions while subtly and mischievously mocking them. It lasts for an hour, and the whole thing is riveting.

There's a moment in the press conference where a very earnest young lady asks Dylan about Donovan: "Do you think he's a good poet?" Dylan noncommittally grunts: "Neh. He's a nice guy, though." The interviewer says, "I'm shattered." Dylan, grinning bigger now, says, "Well, you needn't be."

There's a running joke in D.A. Pennebaker's Don't Look Back documentary where people keep comparing Dylan to Donovan, playing around with the idea that Dylan better watch his back with this kid coming up. Dylan acts politely and insincerely bemused by it. Then, when he meets Donovan and they play songs for each other, Dylan says something nice about Donovan's music. But there's a clear hierarchy to every interaction. Dylan is the heavyweight, the eminence. Donovan's five years younger, and he's lucky to be in the guy's presence.

So Donovan couldn't muster the same voice-of-a-generation resonance that seemed to come so naturally to Dylan. What he could muster was pop music. Donovan's best pop songs -- and there's a pretty good handful of them -- were amiably pretty little pieces of nursery-rhyme nonsense. "Sunshine Superman" is the only one that hit #1, and it's probably also the best of them.

When Donovan recorded "Sunshine Superman," it was 1965, and he was an angelic little kid, a 19-year-old polio survivor from Scotland who'd learned fingerpicking guitar techniques on the British folk scene. He wrote it for Linda Lawrence, an ex-girlfriend of the Rolling Stones' Brian Jones who Donovan had dated for a little while. She'd moved on and moved away, but Donovan loved her. His idea was that he'd write the song, she'd hear it on the radio, and she'd realize that they should be together.

"Sunshine" also was slang for acid, and so the song, with its shambling hippie mysticism and its lyrics about turtles and velvet thrones, was fully in keeping with the early days of the psychedelic era. The song has an endearing lopsided chug and a slick sense of rhythmic interplay. Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones, both working as session musicians at the time, both played on the song, though they brought none of the thunder that they'd conjure two years later, when they formed Led Zeppelin. (Zeppelin, it probably bears mentioning, only had one song hit the top 10 on the US charts, the #4-peaking "Whole Lotta Love" in 1970.)

Decades later, Donovan would talk a big talk about the song, saying that he "wanted to get to the invisible fourth dimension of transcendental superconscious vision." But it's really just a loopy, silly folk-rock love song, and it's a good one. Because of legal issues, the song didn't come out until the summer of 1966. The delay drove Donovan nuts, but it turned out to be a blessing; it's hard to imagine a song any better attuned to that year's zeitgeist.

The song did not get Linda Lawrence to get with Donovan again. Donovan moved on and had a couple of kids with another woman. But four years later, a friend set Donovan and Lawrence up again, and they quickly fell in love and got married. They're still together today.

GRADE: 8/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's Hüsker Dü's "Sunshine Superman" cover, from the 1983 album Everything Falls Apart: