In the first episode of Succession, HBO's great show about the travails of an evil New York billionaire family, there's a scene that's excruciating on a number of different levels. It's the scene where we first meet Kendall Roy, the recovering-addict wannabe tech bro scion of this family. Kendall is in line to take over control of his father's right-wing media empire, and he's on his way to an important meeting. He's in the back of a car, psyching himself up by rapping along with some terrible song. He's all the way into it, doing rap hands and yelling the lyrics. Then the car stops and he gets into character, putting on his remote businessman face. The driver looks at him with some combination of pity and contempt.

And look: That's bad enough. Everything that happens with Kendall during that first season -- really, everything that happens with everyone during that first season -- is bad enough. But it's worse if you happen to feel the shock of recognition, if you know who the model for Kendall is. I watched Kendall rapping and got a sinking feeling in my chest. Oh no, I thought. It's the Rawkus guy.

Today, James Murdoch is the CEO of 21st Century Fox, and he's high up on the ladder of News Corporation, the truly despicable company that his father Rupert founded. (He used to have some even more impressive titles, but he had to back out of them after his company's whole phone-hacking scandal a few years ago.) But back in the late '90s, James Murdoch helped turn the New York rap underground into a financially viable commodity. In 1995, two Brown students named Brian Brater and Jarret Myer formed Rawkus Records, and their friend Murdoch wrote the checks to make it possible.

Today, something like that would be a huge scandal, on the level of Martin Shkreli turning out to be the mysterious businessman who funded Geoff Rickly's Collect Records. But in the late '90s, when word got out that Fox News money was going into Rawkus, I don't remember anyone much caring. This was back before Fox News had successfully mentally poisoned most of the grandparent population of the United States, so maybe that went into it. But there was also some denial at work. Nobody wanted to believe that Rawkus could be connected to something evil. Everyone was just happy that it existed.

Rawkus didn't create the New York rap underground. That already existed. The late-'80s Native Tongues crew wasn't the force that it had been, but its members were still around, and its spirit was informing a new new generation. Rappers like J-Live were releasing independent 12" singles. Stretch Armstrong and Bobbito were playing them on their radio show. Fat Beats was selling them. This whole economy existed. But Rawkus took that scene and popularized it, turning it into something nationwide, the same way that late-'80s Sub Pop had taken the wooly, fuzzed out punk mutations of the Pacific Northwest and turned that whole sound into something you could hear if you did not happen to live in Seattle. This was a valuable contribution.

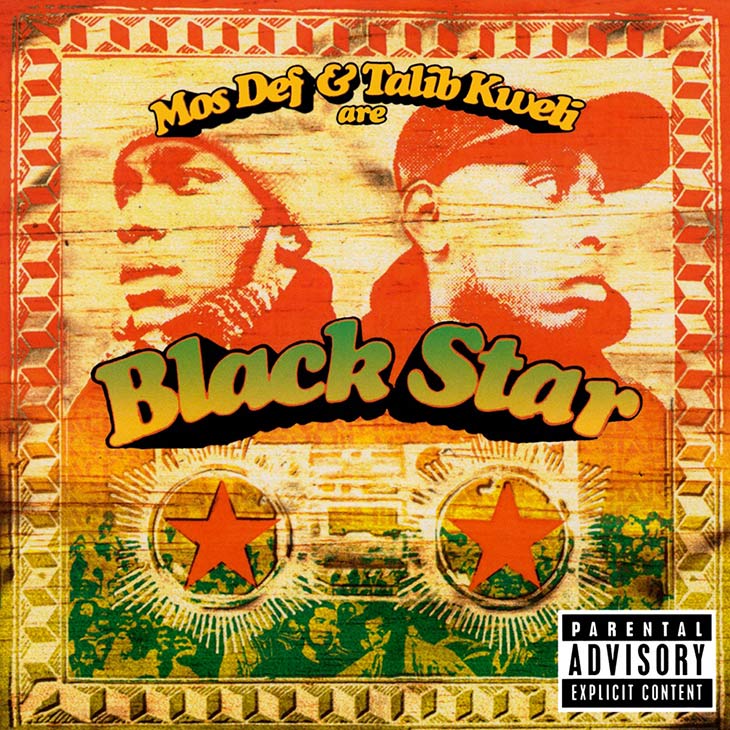

Rawkus had Company Flow, the skronky and experimental New York rap group who'd released the monstrously influential album Funcrusher Plus in 1997. It had Pharoahe Monch, the former member of the cult-favorite major-label refugees Organized Konfusion who'd discovered how to apply his demonically expressionistic style to late-'90s Tunnel bangers. It had Soundbombing II, the compilation that codified the underground rap universe, showing that Eminem and Common and Smif-N-Wessun and Q-Tip all had a place in this little zeitgeist that was happening. But most important of all, they had Black Star.

Mos Def -- now Yasiin Bey -- was a Brooklyn kid who had started out as a child actor. As a teenager, he'd starred on You Take The Kids, a Nell Carter sitcom that had briefly aired on CBS. In 1995, as his rap career was starting, he was Bill Cosby's sidekick on The Cosby Mysteries, a show that ran for a season on NBC. He wasn't famous, exactly, but he was on his way. As a rapper, though, he had an almost defiantly boho sensibility. He'd gotten his first real exposure rapping on De La Soul's 1996 album Stakes Is High. On his early Rawkus singles "Universal Magnetic" and "Body Rock" (the latter of which featured Q-Tip), his enormous, world-swallowing charisma was immediately apparent. He wasn't insular in the ways that underground rappers so often were. He was a star.

Talib Kweli, on the other hand, was insular. Kweli was a classic Afrocentric intellectual, the Brooklyn-reared son of two academics. With the Cincinnati transplant DJ Hi-Tek, he'd formed the group Reflection Eternal, whose1997 single "Fortified Live" was another early Rawkus standout. He'd known Mos from high school, and the two of them turned out to have a yin-and-yang chemistry. They were both furiously talented rappers, but they did different things.

Mos was showy, demonstrative, given to dipping into fake patois or murmuring explosive little melodies. Kweli, on the other hand, was wordy. His lines came out in a rush, like he was doing his best to cram as many syllables as possible into every measure. In his delivery, you could hear mental gears turning, connections being made. He was deliberate. Mos was instinctive. They were made for each other.

I've never really seen a good explanation why Mos and Kweli released an album together before launching their proper solo careers. Maybe they both knew that they were still figuring things out. Maybe they were too nervous to fully present themselves to the world, so they figured they'd step into the spotlight together. Maybe they just recognized the kind of chemistry that they had. Whatever the case, Mos Def & Talib Kweli Are Black Star arrived at the exact right time. The world was ready for it.

A year earlier, rap had just seen the flashiest summer in its entire history. With Bad Boy suddenly dominant -- not just over rap but over pop music in general -- rap's commercial potential was suddenly realized, more than most people had probably ever thought possible. Rappers were competing to show who could display money in the most ostentatious ways, who could flex the hardest. The backlash was inevitable. That backlash took a lot of forms. One form was Lauryn Hill's lush, organic open-wound soul. Another was DMX's urgent, guttural slash-your-throat street rap. And another was what Black Star were doing.

Mos and Kweli knew what they were doing. They'd consciously positioned themselves as an alternative, a proudly bookish reaction to the endlessly flashy pop-rap of the era. They nodded toward '80s fundamentalism, using the beat from Boogie Down Productions' "Remix Of P Is Free" on their single "Definition" and repurposing Slick Rick's "Children's Story" to turn it into a tale of a greedy rap kid who jacks too many obvious samples. They dedicated an entire song to breakdancers. They spent an entire chorus quoting Toni Morrison. They devoted their most sensual song specifically to dark-skinned black women.

Black Star used a lush, warm production style -- much of it from Kweli's Reflection Eternal partner Hi-Tek -- that called back to mid-'90s Tribe Called Quest, who would've probably been their closest peers if Tribe had managed to keep it together. (Instead, Tribe were in the process of breaking up; The Love Movement, Tribe's final pre-breakup album, came out the same day as Black Star.)

Essentially, Mos and Kweli recognized an open lane when they saw one. Rap was bigger than ever, but the Afrocentric pride and soulful warmth of early-'90s rap were disappearing from the genre's mainstream. So they presented themselves as antidotes to all that shallowness. They namechecked Marcus Garvey and Duke Ellington. They criticized their mainstream-rap peers, but they also went after Rudy Giuliani and Eurocentric beauty standards. They weren't hectoring gatekeepers. They were welcoming and accessible, full of hooks and punchlines and quotable slogans. They came off like the kid in your dorm who's both smart and likable enough to lead a sweatshop-divestment protest that embarrasses the college into changing its business practices. They were idealistic, and they were effective. They had an act, and their act worked.

Black Star's success was, at least on some level, a triumph of marketing. But the marketing wouldn't have worked if the album wasn't good. And the album was great. For an album with so many producers, it was remarkably cohesive, it's hazily delayed thump consistent from one track to the next. The album had party songs, but its heart was the second half, the headphones songs. Those were the songs where the duo reflected on slavery's legacy or on the way the city air feels at night.

Mos was a revelation, of course. He sounded fully of joy and fire, like he was just discovering how good he was at rapping and he couldn't wait to show it off: "These simpletons, they mentioned in the synonym for feminine." At the time, I liked Mos a lot more than the more verbose and considered Kweli, but listening to the album now, I find myself rapping along with Kweli's lines at least as often. Kweli's choppy flow has its own internal logic, like puzzle pieces fitting together. He always sounded like was about to stumble over his own voice, but he never did.

I was about a month into my freshman year at college when Black Star came out, and I was ready for it. The album came out the same day as new albums from Jay-Z, OutKast, and Tribe, but the two albums I bought that Monday at midnight were Black Star and Soul Coughing's El Oso. (Don't judge me. Only God can judge me.) Black Star flattered my idea of myself as a discerning listener, as someone who was on the right side of some imagined rap civil war. I thought of Black Star as the opposite of Jay, who I saw as some kind of crass salesman. That feeling was wrong -- five years later, Jay basically rapped that he wished he could rap like Kweli -- but it was central to Black Star's initial buzz.

And yet that initial buzz wasn't what lasted. Black Star was a strong enough album to stand on its own, divorced from that whole late-'90s context. Listening to Black Star today, it's not a perfect album. There's some regrettable homophobia, as well as a few songs (I'm thinking "Children's Story" and "B Boys Will B Boys") that would be YouTube videos, not album tracks, if someone made them today. And yet the album functions as an argument for its own vision of rap. And it functions as a really, really good rap album.

Mos and Kweli have stayed close, often rapping on each other's records, but they still haven't made another Black Star album. (They tease us with the possibility sometimes, so it could still happen.) They went on to great solo careers of their own, though I don't think I've ever loved either of them separately as much as I did together. They became cult heroes. In the summer of 2000, I worked at a Central Park show where the Roots brought out Mos and Kweli as surprise guests, and the crowd's rapture was as loud and pure as any I can remember. For a few years after Black Star, that kind of reaction, within certain circles, probably followed them wherever they went.

But Mos Def & Talib Kweli Are Black Star was not a massive hit. It charted, and so did its singles, but only in Billboard's lower reaches. Rawkus couldn't compete with Bad Boy, but it could carve out a niche, and an album as great and word-of-mouth-friendly as Black Star was essential to that niche. And Black Star planted seeds. Mos and Kweli never became pop stars, though both command huge audiences and, I'm sure, lead comfortable lives. But the album captured the imaginations of plenty of idealistic young people, and plenty of those young people went on to do things. Six years after Black Star, for instance, both Mos and Kweli showed up on Kanye West's College Dropout, their presence working as a signal of the way they'd help shape West's idea of what rap could be.

And if Rupert Murdoch's kid didn't have some extra money lying around -- if he didn't love rap music -- maybe none of this could've ever happened. I don't know what to do with that. Steve Mnuchin was an executive producer on Mad Max: Fury Road, you know? Sometimes, I guess these assholes find something good to do with their money.