Everything about Polly Jean Harvey was a revelation when she emerged in the early '90s. Her first two albums with the trio PJ Harvey, 1992's Dry and 1993's Rid Of Me, were both as raw and tender as a newly scraped knee, all electric guitar fury and abrasive vocals. In 1995, Harvey stepped out on her own with the solo effort To Bring You My Love, an austere marvel steeped in blues and folk that smoldered and seethed as it reached the Top 40 on the US album charts and spawned a #2 modern rock hit, "Down By The Water." This trilogy established Harvey as a formidable voice on both gender stereotypes and sexual expression, a powerhouse unafraid of aggressively confronting (and then upending) conventions.

As the decade progressed, this heightened profile came paired with increasingly loud stage-whispers that she had an eating disorder, along with lingering misconceptions about her mercurial moods. "I'm a mad bitch woman from hell. I can't get enough sex or blood!" Harvey said, somewhat facetiously, when asked in a 1994 Q interview if she knew how the public considered her. She certainly wasn't the only woman in the '90s to be flattened into a caricature (just ask her Q interview mates, Tori Amos and Björk, who were also often side-eyed with unflattering assumptions) but in Harvey's case, the pigeonholing felt particularly pernicious.

Perhaps because she didn't shy away from anger or sexuality -- and was a young woman expressing anger, at that -- her persona was scrutinized more closely. "On the first couple of albums, I was finding a voice for the first time to say an awful lot of stuff that was stored up inside me," Harvey told The Times in 1999. "I was very young and confused, so yes, those early albums are very angry. I was exploring that and finding a way to express it, and thought there is joy and a vibrant energy there, too. But you get categorized and it becomes rigid, and it doesn’t allow you space to develop and grow."

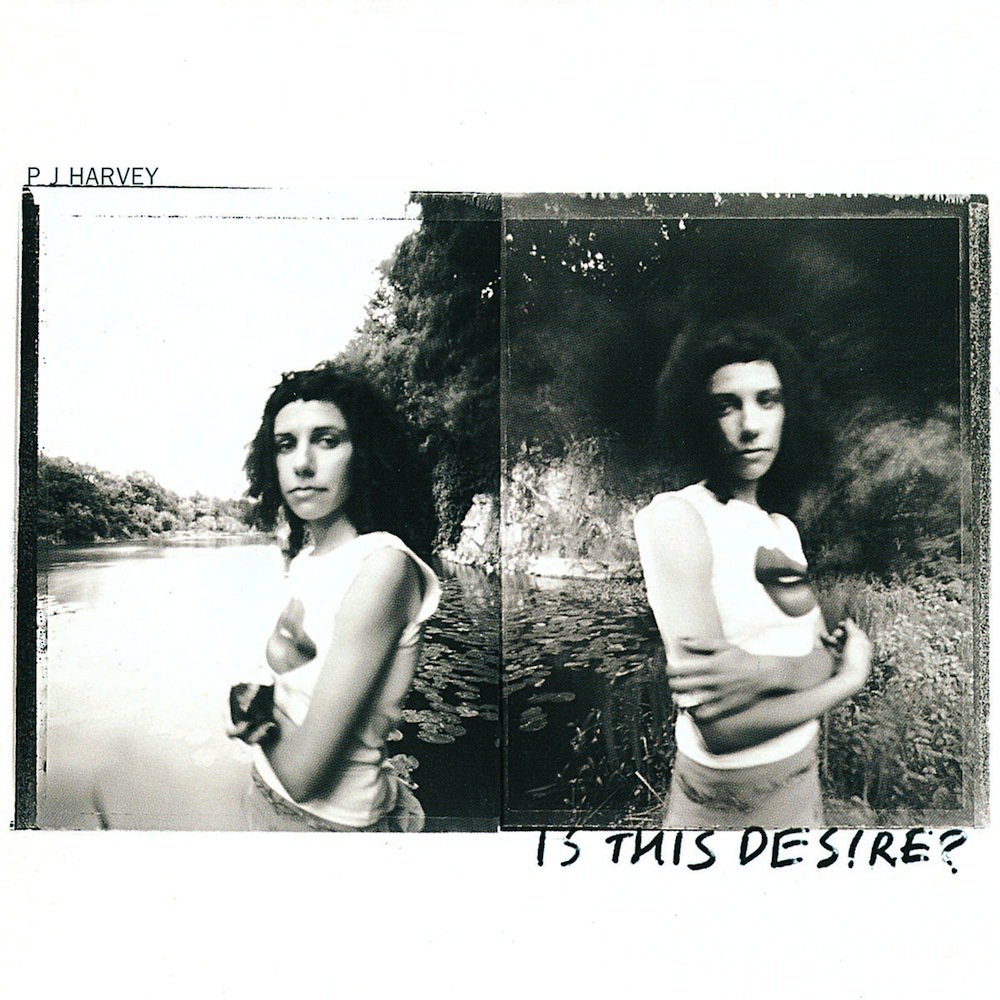

Released on September 28, 1998, Is This Desire? didn't quite reach the chart peaks of To Bring You My Love in most countries. However, commercial success was somewhat beside the point: The album obliterated expectations and found Harvey wresting control of her own narrative. Is This Desire? represents the culmination of her carving out time for self-care, emotional growth, and intense reflection -- and channeling this into the lyrics. "I wanted to write for myself, about myself. Like someone looking in on me," she explained to The Observer in 1999.

In some cases, this took the form of metaphorical concern. The lyrics of "The Wind," a song inspired by the hillside St. Catherine's Chapel in Harvey's hometown of Dorset, England, envision the titular saint ensconced in the place of worship, where she "sits and moans." However, the last verse features a child wishing Catherine could have a husband -- and although the real saint was said to be devoted to Christianity rather than earthly desire, it's a sweet, empathetic gesture underscoring that the melancholic woman isn't alone.

But the title track -- on which a man asks a woman, "Is this desire, enough, enough/ To lift us higher? To lift above?" -- crystallizes the album's central lines of questioning. Possessing desire is one thing, but what are the complications of expressing this desire? And is desire alone enough of a sustaining force -- or can it also be a tool of destruction? These are thorny questions with no easy answers. "The Garden," for example, envisions the tale of Adam and Eve unfolding between two men instead, but even a romantic encounter doesn't change how lost the protagonist feels. In this case, having a taste of forbidden desire isn't enough. Yet "The River" describes a relationship scorched by conflicting, greedy wants; it's a case of too much desire having a negative effect.

Is This Desire? is particularly moving when it articulates how complicated desire affects women. The protagonist of "A Perfect Day Elise" witnesses the suicide of a beloved; "Catherine" is from the point of view of someone spurned by (and deeply jealous of) the titular character; "Joy" is consumed by "her own innocence" and feels so hopeless she'd rather go blind than remain in her current state.

It's poignant (and pointed) that so many of the women on Is This Desire? have names: These aren't abstract embodiments of femininity or womanhood, but relatable characters who are in various states of emotional disrepair, unmoored by forces beyond their control. Anyone listening to Is This Desire? could be a Joy or a Dawn or Elise; in fact, these named women feel like metaphorical selves representing Harvey's own traumatic journeys. Accordingly, her vocal performances channel these different personas. "Catherine" has a regal, velvet-trimmed tone; "The Wind" alternates between conspiratorial whispers and a soaring falsetto; and the bruising "A Perfect Day Elise" contains notes of panic.

The period that produced Is This Desire? also gave Harvey valuable insights into her own psyche. As she told The Observer in 1999, hearing the playback of the song "My Beautiful Leah" -- starring a sadness-wrecked woman who feels she'd be better off dead than remain alone -- in particular, shook her. "I listened back to that song and I thought 'No! This is enough! No more of this! I don't want to be like this.' Because it was all so black and white, and life just isn't black and white. I knew I needed to get help. I wanted to get help."

She went into therapy and, at some point, also moved into the basement flat of a house owned by her bandmate and collaborator John Parish, and video and art director Maria Mochnacz. The gesture represented more than just goodwill: "They basically saved me," Harvey admitted to The Observer. "I needed to be rescued, and I was." She recalled writing songs for Is This Desire? in this subterranean space, which was dark and cloistered, and focused on the demos her flatmates liked the most.

Unsurprisingly, Is This Desire? also sounds very different from Harvey’s prior work. Although there's no shortage of abrasive moments (e.g., distorted vocals on "No Girl So Sweet"), Harvey de-emphasizes guitars in favor of stormy electronic programming with roiling rhythms and skeletal keyboards. Her collaborators aid and abet these gothic-dark soundscapes: The sparse "Angelene," which boasts brooding piano and funereal organ, was arranged by long-time Nick Cave associate Mick Harvey. Marius de Vries, fresh off his work on U2's Pop and the Romeo + Juliet movie score, also contributed additional programming, notably on the witchy shuffle "The Wind," which boasts reedy percussion and haunted house-creepy electronic effects.

Unlike other late '90s albums that incorporated electronics, Is This Desire? has aged far better, perhaps because the musicians were so deliberate about sculpting these dark moods. "Writing on different instruments changes the way the songs come out," she told The Observer. "I used to write all my songs on guitar, and they come out physically different to the ones you write on keyboards, which is what I did for Is This Desire?" Additionally, rather than try to replicate her four-track demos, the production team loaded Harvey's work into a multi-track recorder, and used them as the sonic foundation for the album.

However, recording Is This Desire? was another fraught process. Harvey and her production collaborators, Flood and Head, did the first recording sessions in 1997, and then walked away from the music. "I chose to just leave it for a while," she said in an interview disc accompanying the album. "I was doing a lot of emotional work at that time, and I just needed a break from everything. I just wanted to stop and start looking at my life as Polly, rather than my life as a songwriter-performer."

The pause was the right move: When she revisited the material in April 1998, she was in a much better headspace and had a much clearer vision of how to finish the album. "An important part of the creative process is knowing when it is the right time," she told The Times. "The songs weren’t ready, and nor was I." Harvey didn't touch some songs, but re-cut vocals for others and even re-recorded a few. "It was really basically just bringing them back to where I am now," she said in the interview disc. "I think I'd moved on quite a lot in those couple of years, so I wanted to, like, bring them into the fold of where I am."

One of the most important elements of this personal growth was Harvey deciding to be kinder to herself. "You come to a point where you have to allow yourself to like yourself a bit more," she told The Times. "I used to feel I didn’t deserve it. That was always seeing the negative again. Now I have learned to say it’s all right to like yourself." As for how she was able to get to this point, she cited age ("One develops a much larger perspective on life") but also life's vicissitudes. "There has been a lot of death around me, people I know. But there have been quite a few births around, too -- friends of mine having children. That broadens your horizons. It has allowed me to see what is worth worrying about and what isn't."

This better mindset isn't necessarily evident on much of Is This Desire?, save for two poignant songs. Rather than focusing on darkness, "The Sky Lit Up" touts the brilliant parts of a night scene (e.g., moon, stars) as a backdrop to describe romantic optimism; appropriately, she expresses this ecstasy via a cathartic shriek. The protagonist of "Angelene," meanwhile, daydreams of escaping her current life, where "love for money is my sin," for her true love, located two thousand miles away: "I've heard there's joy untold/ Lays open like a road in front of me." These women dare to dream of personal freedom and happier lives.

With the release of Is This Desire?, Harvey too could count herself among those women. The album didn't just open her up to new musical vistas -- it helped her figure out how to live and be comfortable in her own skin. "You know, I'm 28; it won't be long til I'm 30," she said on the Is This Desire? interview disc. "And then you start thinking, 'What is life all about?' And so then you start doing a bit of digging around."

"I've done an awful lot of that and unearthed a lot of unpleasant things and a lot of very pleasant things. And I think all of that comes across in the new songs and in my voice. I think for the first time in my life I can say that I'm singing with a voice that is my own, which is Polly, which isn't wearing a mask or playing a part, but it's me."