I interviewed Lil Wayne once. This was sometime in 2006, when Wayne was deep in his historic mixtape run, when he hadn't yet achieved his final pop-star form. It was a last-minute thing. I'd been trying to talk to Wayne for months, and someone finally called me on my Village Voice office phone and told me Wayne would be calling in 15 minutes. At the time, I was in love with everything Wayne was doing, but I was especially in love with "Shooter," the Robin Thicke collaboration that he'd released on his album Tha Carter II a few months earlier.

Too nervous and excited to translate my thoughts into coherent interview questions, I basically demanded that Wayne release "Shooter" as a single. And in doing so, I told him that I thought he finally had his "Hard Knock Life." Wayne liked this. He made a sort of appreciative back-of-the-throat croaking sound, the kind he often makes on records: "Ohhhhhh! I need that! I been telling people! I need my 'Hard Knock Life'!"

He made "Shooter" a single pretty soon after that, something he'd already been planning to do. It didn't go anywhere. Wayne finally had his "Hard Knock Life" two years later, and it was "Lollipop."

You need that one song. That one song can change everything. You can line everything up perfectly, but if you don't have that one song, it won't work. In 1998, Jay-Z had everything lined up perfectly. He had observed and understood every trend happening in rap. He knew, for instance, that there was a void at the center of New York rap, a void that his old friend Biggie Smalls would've filled if he'd survived to fill it. The flashy, excessive Bad Boy sound still had some steam, but it was on its way out. With "Come With Me," Puff Daddy's widely hated song from the Godzilla soundtrack earlier that summer, the backlash had finally overwhelmed the wave. Jay-Z also saw his friend DMX exploding with a sound that reacted hard against Bad Boy's primacy. Bad Boy was flashy and bright and melodic. DMX was dark and guttural and mean. Jay somehow found a way to combine those opposing threads, to pull them into one seamless whole. He made hard, unflinching New York street music that resonated as pop.

Jay did other things, too. He recognized the ascendance of Southern club-rap, and so he figured out how to put a bounce into his flow. He jumped awkwardly onto a remix of Juvenile's "Ha." It didn't work, but it must've been a learning experience. On his own album, Jay figured out how to master that flow without compromising his blank, hard New York delivery. He brought Timbaland in to produce a couple of tracks, and he turned one of those tracks into a breathless fast-rap clinic. Jay also recognized the appetite for crime stories, and he told those stories, packing them with granular detail and seen-it-all experience. He'd built up the goodwill of releasing two very good albums and shining in every guest appearance. He had flows and hooks and punchlines. He had everything lined up. And then, blessedly, he had that one song.

One night when he was opening up Puff Daddy's No Way Out tour, Jay heard a familiar sound. The producer Mark The 45 King had taken a sample from the musical Annie, all these little girls braying happily about how they lived a hard-knock life. The 45 King had taken that chorus and built a big, blocky rap beat out of it. Kid Capri, who was DJing that tour, played a dubplate of the 45 King's beat. Jay heard it, and he knew he needed it. Once he had the chorus, the rest of the song came easy. Honestly, all Jay had to do was stay out of that hook's way. The song had already done all the work for him.

In his book Decoded, Jay writes about how he got approval to use that Annie sample. To clear that sample, Jay wrote a letter to Martin Charnin, the song's lyricist. In that letter, Jay told a story about how he'd won an essay contest in seventh grade. As the prize, he got a trip to Manhattan to see Annie on Broadway. In the letter, Jay wrote about the feeling he had seeing that play -- the feeling that he was seeing his own story playing out on the stage. It was all a lie. Jay never won an essay contest, and he never saw Annie on Broadway. He saw the movie on TV, like everyone else. The lie worked. Jay had his sample, and he had his one song.

"Hard Knock Life" hit a chord. It hit multiple chords. Jay might not have seen Annie on Broadway, but he understood something about that song. He understood that "Hard Knock Life" was a celebratory song, a song about the pride that comes from enduring hardship. He put that feeling into his own story, the mythic tale of the street-corner hustler who comes up through the ranks and then makes the transition to rap glory. He found some version of the Annie story in his own, and he did it without making the connection too obvious. If you were coming from a certain place, you could hear Jay reflecting his own struggle in a fresh and fun way through that song. If you were coming from a different place, you could hear an old show-tune that you loved, now with rapping on it! Everything clicked. The song did what the song needed to do.

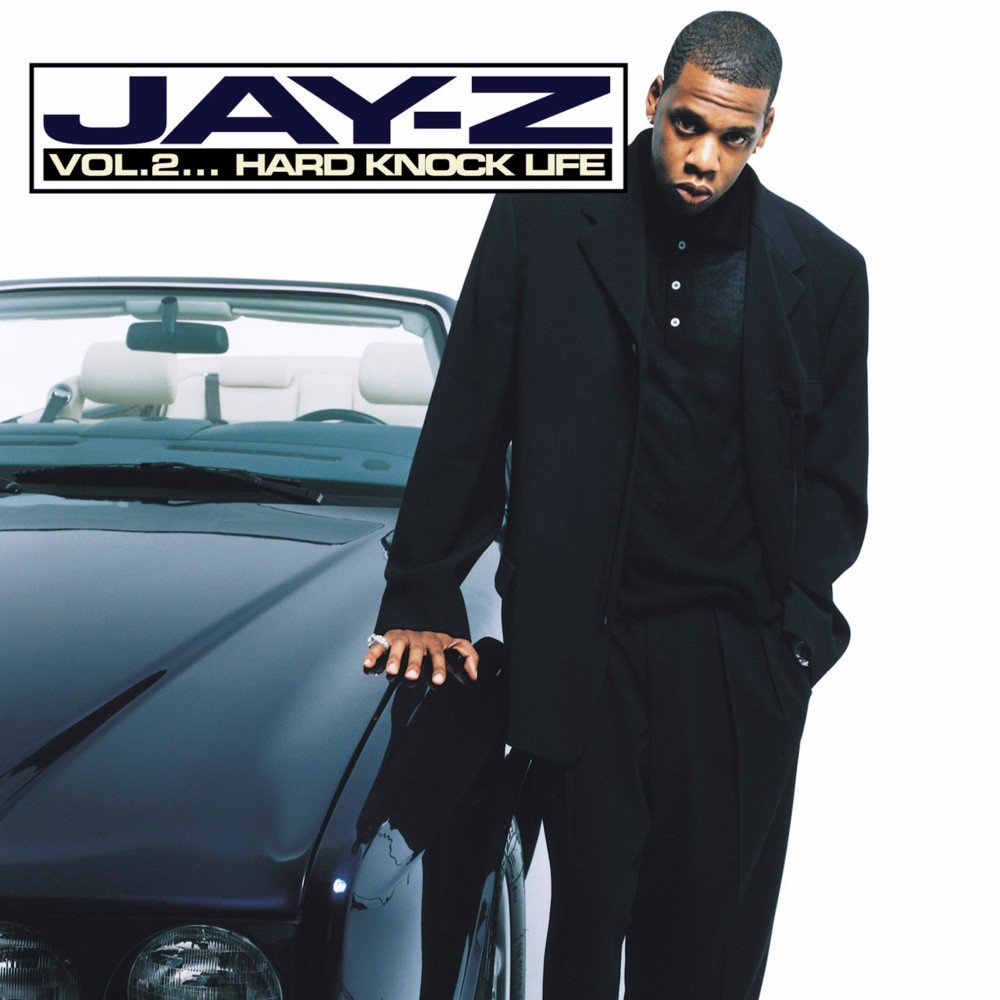

As someone who'd just arrived on campus in his freshman year when "Hard Knock Life" hit, I can confirm that the song was immediately enormous -- the kind of thing that you would hear five times at every party, with every white kid in the room rapping awkwardly along. The song's omnipresence became oppressive, and to this day, it's my least favorite song on Vol. 2... Hard Knock Life, Jay's masterful third album. But it didn't matter what I thought of the song. The song did its job. It turned Jay into a star.

What you hear on Vol. 2 is Jay realizing his own stardom, stepping fully-formed into it. Vol. 2 sold five million copies within two years. It's still Jay's best-selling album. Listening to Vol. 2 today, it's amazing that an album this harsh could've been a pop sensation. Jay had already honed his persona, and the character he plays on Vol. 2 is a cold-blooded kingpin, a titan of street industry hardened by all his time on the other side of the law. All through Vol. 2, Jay never displays a single vulnerable emotion, unless you want to be really generous and claim that he's hiding, say, romantic anxiety within the misogynistic disgust of "Can I Get A..." or hurt in the betrayed disgust of "A Week Ago."

And yet Jay makes for a compelling three-dimensional figure anyway. He talks about his time in the drug trade with a masterful detachment, almost like he's talking about someone else. But if you're listening close enough, Jay gives more game in Vol. 2 than all the narrators in all the Scorsese mob flicks combined. On his songs, you could even take away workplace lessons that extend far beyond the drug-dealing world that Jay describes. "A Week Ago": how to deal with a deceitful, malicious co-worker who used to be a friend. "Coming Of Age (Da Sequel)": how to manage a rebellious, impatient underling; getting maximum productivity out of this worker while also guaranteeing his workplace satisfaction. "Paper Chase": how to assemble a new team in an unfamiliar city. It goes on.

The Jay of Vol. 2 was also at the absolute apex of his disdainful mastery. I first moved to New York a year and a half after Vol. 2 came out, and I had a minor revelation there: Jay was the king of New York because he sounded like he believed every last thing he said. There's an overwhelming confidence in the way he describes how great he is. And when you're in New York, a city absolutely jammed with desperate strivers trying to project themselves to be bigger than they are, Jay's calm matter-of-fact excellence speaks volumes. He never had to huff or puff like so many of his peers. He just said it, and it was so.

That all-consuming self-assurance, that perfectly evident belief in his own greatness, made for a very effective form of charisma. That's what allowed Jay to sniff at all his competitors like they were barely even there: "What's the dealings? It's like New York's been soft ever since Snoop came through and crushed the buildings." That's what let Jay try out the tricky stop-start rapping of "Jigga What, Jigga Who." That's what let him claim that he had a condo with nothing but condoms in it, which seems like an inefficient use of apartment space.

And that confidence is what allowed Jay to put together an all-star team of the East Coast's hardest rappers for the devastating posse cut "Reservoir Dogs," everyone rapping over a weaponized sample of "Theme From Shaft." The lineup is ridiculous, relentless: The Lox, Beanie Sigel, Sauce Money. All of these rappers are competing to come harder than all these other rappers, all of them giving their most devastating punchlines. Styles P, for one, gives what might be the single best line of his whole entire career: "I don't give a fuck who you are, so fuck who you are." And Beanie has the hardest recorded use of the word "vestibules" in the history of the English language. But Jay knows that he can show up at the end of the song and show everyone else up. And that's exactly what he does: "How the fuck is you gon' stop us with your measly asses? / We don't stop at the tolls, we got EZ Passes."

And Jay also understood what music worked best with his voice. If you count the bonus tracks, there are six singles on Vol. 2, all of which were inescapable. Those songs managed to be huge despite being full of sex and murder and malice. On "Can I Get A...," Jay might not say one single non-bleep-worthy line that isn't "bounce with me, bounce with me," and that song still blew. (Ja Rule's compellingly fired-up verse on that song is basically the only reason Ja Rule ever got to have a career. Just think: If Jay had put the real DMX on that song instead of the fake DMX, the Fyre Festival never happens.) And even the songs that aren't singles, including the deeply involved drug-trade narratives, sound like they could've easily been singles. Vol. 2 plays like a readymade greatest-hits album, and the transition from "Jigga What, Jigga Who" into "Money, Cash, Hoes" still makes me feel like I could headbutt a Range Rover and knock it on its side.

Years after Vol. 2, Jay settled on his elder-statesman sound -- a theatrical big-stage version of '90s New York rap, with soul samples chopped up but left lush. We can hear a few distant echoes of that on Vol. 2. There's the regal burst of horn on "Money Ain't A Thang," a huge hit for Jermaine Dupri that became a Vol. 2 bonus track. There's the ingenious Talking Heads "Once In A Lifetime" sample of "It's Alright," another bonus track that had already been on Jay's Streets Is Watching soundtrack. There's the chilly DJ Premier beat on "Hand It Down" and the tense Isley Brothers chop on "A Week Ago." But Vol. 2 also shows a version of Jay that sees and adapts the trends of the era. So Jay sounds absolutely at home on those riotous, ungainly Swizz Beatz tracks, the ones that sound like a toddler banging on a Casio. And he sounds even more at home on Timbaland's computerized alien funk. He's effortless on all of it, a master of the rap landscape. And in the 20 years since Vol. 2, we still haven't heard anything like that deathless arrogance again -- from Jay or from anyone else.

Vol. 2 came out on the same day as OutKast's Aquemini. It debuted at #1, while OutKast only hit #2. (There's a fascinating mini-history of Jay/OutKast release-date battles. I always loved the rumor about Def Jam filling a warehouse with CD copies of The Dynasty: Roc La Familia so that it could beat Stankonia to #1.) Despite the mutual admiration between Jay and OutKast, despite the way they'd later collaborate with one another, it's so weird to think about Vol. 2 and Aquemini occupying the same time, the same space. They are just vastly different albums, with different sounds and ideas and goals. But the truth is that they're both classic albums. They're just classic for different reasons. OutKast went internal, crafting a masterpiece of dizzy funk and astral thought-trails. Jay, meanwhile, harnessed everything that was happening in rap at that moment, and he put it all in service of his own persona. He told us that he was the best, and we believed that shit. And once he found the right song, he turned himself into the biggest star in the world.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]