It must be incredible to walk the earth with Bradley Cooper’s confidence. The man decided that he was going to remake A Star Is Born, a film that has already been made four times (five if you count 1932's What Price Hollywood?, which inspired the 1937 original). Not only was Cooper going to co-write and direct this film, he was also going to take on one of the two leading roles. Oh, and in order to do that he had to learn how to play the guitar and the piano and how to sing like a decaying rock star. This was to be Cooper’s directorial debut, his great unveiling as an auteur, and instead of making some cute little indie he planned to go blockbuster big. In order to achieve his dream, Cooper had to go into a room of producers and pitch the idea. Miraculously, he walked out with their blessings and $38 million.

If you have seen the 1976 version of A Star Is Born then you will understand how insane it is that anyone thought remaking it yet again was a worthwhile endeavor. The 1976 version of A Star Is Born, the interpretation this new remake most resembles, is not good. Barbra Streisand and Kris Kristofferson lack chemistry, and while the story is supposed to teach viewers some kind of lesson about fame and its excesses, there are far too many moments that border on farce, favoring spectacle over narrative structure. While there is plenty of spectacle and melodrama in the new version -- and some scenes from the film directly mirror that of both the '76 and '54 versions -- the lessons presented here are less obvious. Cooper is trying to say something profound about Art with a capital-A. His vessel is this titanic love story.

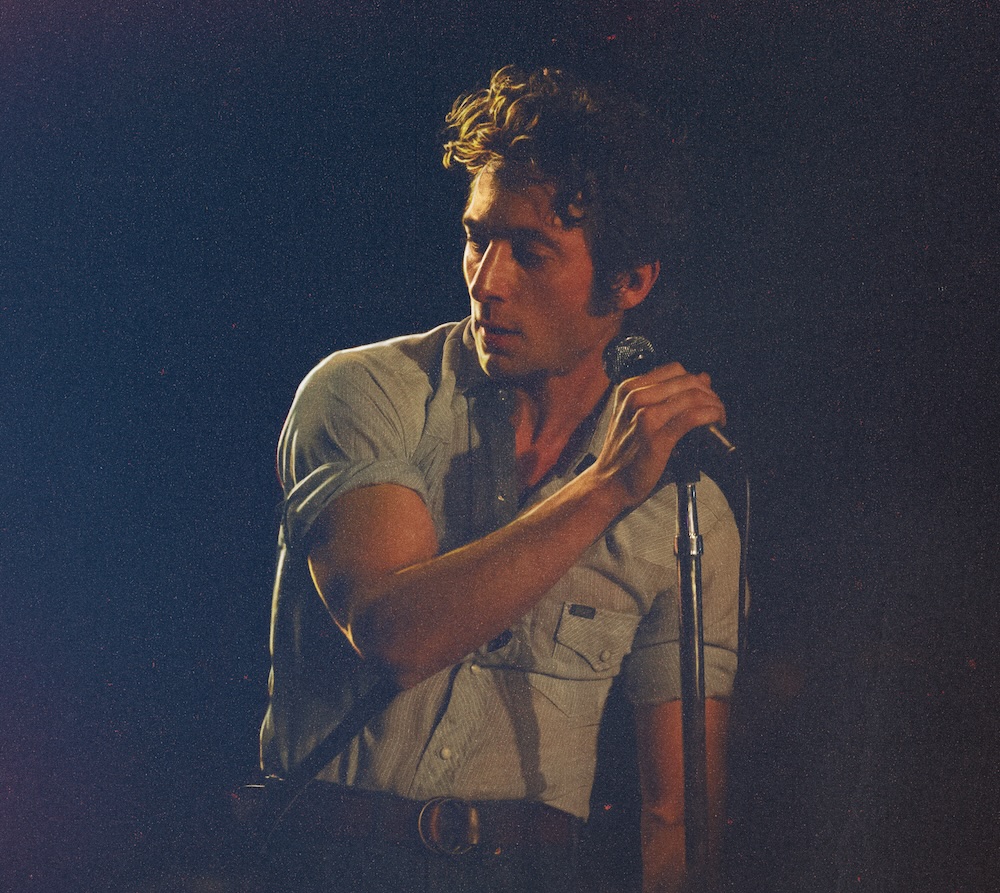

A Star Is Born follows Jackson Maine (Cooper), an alcoholic and drug-addicted musician who falls in love with a cabaret singer named Ally (Lady Gaga). By his side, she becomes a famous pop artist, and as her star rises, his burns out. Jack's music can be described as folky, country-ish Americana (his big hit was written by Jason Isbell). He is famous enough to be recognized in public but not so famous that he doesn’t have to do an embarrassing corporate retreat performance every now and then. When Jack drinks and uses drugs he is funny and open. When he doesn’t, he is withdrawn and afraid of the world. This is a story we've heard before.

Ally, by contrast, is less haunted. She’s younger than Jack and a server at a hotel restaurant. She still lives at home with her dad, who owns a car service. Ally dreams of being a performer, but every time she’s gotten into a room with record executives, they tell her she’s not pretty. This is something that Gaga herself struggled with early in her career, and Ally’s story is closely tied to Gaga's own. When Jack and Ally first meet, she tells him that she hates her nose and he tells her that he loves it. He then proceeds to reach out and run his fingers along her profile in slow-motion.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

The chemistry between Gaga and Cooper is undeniable -- I will even go as far as to say that it is extremely hot. Had they not been so at ease with one another, A Star Is Born would be a tremendous failure. This is a whirlwind romance and the stakes are only as high as the leading couple can make them. As an actress, Gaga is so in touch with her character that it’s easy to forget she’s Lady Gaga until Ally dons a blue velvet pantsuit and bangs out an epic anthem on piano in front of thousands of fans. Cooper's own singing voice, while no real match for Gaga's spectacular Broadway howl, is aching and beautiful. When the two perform the film's rousing single "Shallow" together for the first time, it’s genuinely stirring, a moment of perfect cinema.

Discord between the couple is sewn by two things: music industry leeches and Jack's addictions. While earlier iterations of this film might’ve painted Jack's alcohol and drug dependencies as unfortunate side-effects of working in a crazy industry, this new script treats them as an intrinsic aspect of his personhood to an unsettling degree. We are made to assume that had he not become famous, Jack would probably be dead because no one would be getting paid to look after him. But in spite of his instability, Jack grows increasingly more judgmental of Ally. As he watches her compromise her artistic vision with that of her sleazy manager (Rafi Gavron), Jack tells her, “If you don’t dig into your fuckin’ soul, you won’t have legs,” meaning that music without heart is not music. It’s product. Ally, happy to finally be where she always hoped to be, doesn’t see it the same way. Her naïvety, coupled with her talent, propel her to fame.

This is a conflict that arises in every movie that has ever been made about show business. It’s an especially frustrating debate to introduce to this movie because it presumes that the music Jack makes (heartland rock) is somehow more authentic and artful than the pop-inclined music that Ally starts writing with her team. Those who are more invested in music than a typical moviegoer might wonder: Does it matter if a song comes from deep inside your soul as long as people enjoy it? Since Lady Gaga is playing the role, it's obvious that the answer to this question is: "Of course not." Jack's disdain is directly tied to his fear of being left behind. The rest of the world is already forgetting about him; in his depressive state it seems only natural that Ally will follow suit.

Like Ally, Gaga exists in the realm of pop, but she is fortunate to have built a career on being an outsized version of herself. When Gaga broke out she was considered a true pioneer of our contemporary pop landscape. Gaga opted to be weird and freakish, to take whatever she once might've thought was ugly about herself and amplify it. She is a remarkable singer, but her sense of self -- which never seems to waver, no matter how many costumes she puts on -- is her selling point. If we are to presume that Ally continues to grow and develop as a mainstream star, then perhaps we might imagine her having that kind of career once she's able to shake the industry snakes.

It's not presumptuous to assume that Cooper is personally invested in debates over authenticity. In a recent New York Times profile he assumed the role of a haughty and self-serious director, refusing to answer questions about his relationship to Jack, a character that he plays with so much empathy that, at times, it can be painful to watch his performance. But as impressive as this film is, it's not like, Buñuel. It’s interesting that Cooper -- an actor who is known for playing vacuous men with an intensity that suggests he would like to be taken a lot more seriously -- would want to make this specific film, which has never been thought of very seriously. It’s also interesting that Cooper, who is 11 years sober and an artist thankyouverymuch, would want to play a guy like Jackson Maine. Is Cooper trying to tell us something about Art or about Himself? Both, I think.

A Star Is Born has the quality of a daydream. Anyone who has ever hungered for a life that's bigger than the one they've been given will be familiar with this fantastical storyline: Plucked from obscurity, a young and gifted misfit suddenly has it all. What gives this version of the film gravity is the obvious care that was put into the backstories and character development of its protagonists. Jack and Ally feel real. Their love feels real. Their arguments feel real. The lights, the stage, the stuff that cost $38 million to recreate, is all just seductive backdrop. The freedom that comes with fame, in the end, is still limiting.

There is a scene in A Star Is Born where Jack’s loving but stern tour manager and brother, Bobby (Sam Elliott), shares some wisdom with Ally. In his gravelly voice, he explains to her that every song tells "the same story over and over," that it's the artist’s job to rewrite it in a way that feels true. He’s talking about tragedy and triumph and heartbreak and the human condition. He's talking about this movie, too.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]