She was in and out of mental hospitals and drug rehabs constantly. Then she wrote a note about going to join our father in a parallel universe, swallowed a bottle of pills, and killed herself for real this time.

--Mark Oliver Everett, Things The Grandchildren Should Know

Eventually her breathing began to slow down until it was very, very slow. And then there was one last, slow exhale with no inhale after it. It hit me hard. Even though I had known it was coming for some time, my mother had just died, right in front of me. I laid my head on her lap and wept uncontrollably. It was November 11th, my father's birthday.

--Mark Oliver Everett, Things The Grandchildren Should Know

The mid-to-late '90s were a fascinatingly odd time for alternative rock radio, often in a way that is more interesting to think about in retrospect than it was to experience in real time.

Kurt Cobain was gone and most of the original grunge stalwarts weren't doing so well either. Korn and Limp Bizkit were lurking, eager to remove any strain of progressivism or art from the landscape, but they hadn't quite taken hold yet. For a time, programmers and MTV were throwing it all against the wall like so much major label wet spaghetti. Surely some of it would stick to the kids. What was it these little bastards wanted? Ska? Swing? Some other retro-pastiche? Post-grunge scrunge rock? Electronica? Post-Beck hip-hopish rock? Ben Folds Five, maybe? The "let's give everyone a record deal and Buzz Bin rotation and let God sort 'em" approach led to a lot of strange radio singles (I'm glad Cornershop happened but I still can't believe Cornershop ever happened) and some very crowded new arrival sections at the used-CD store. (Pour one out for the used-CD store.)

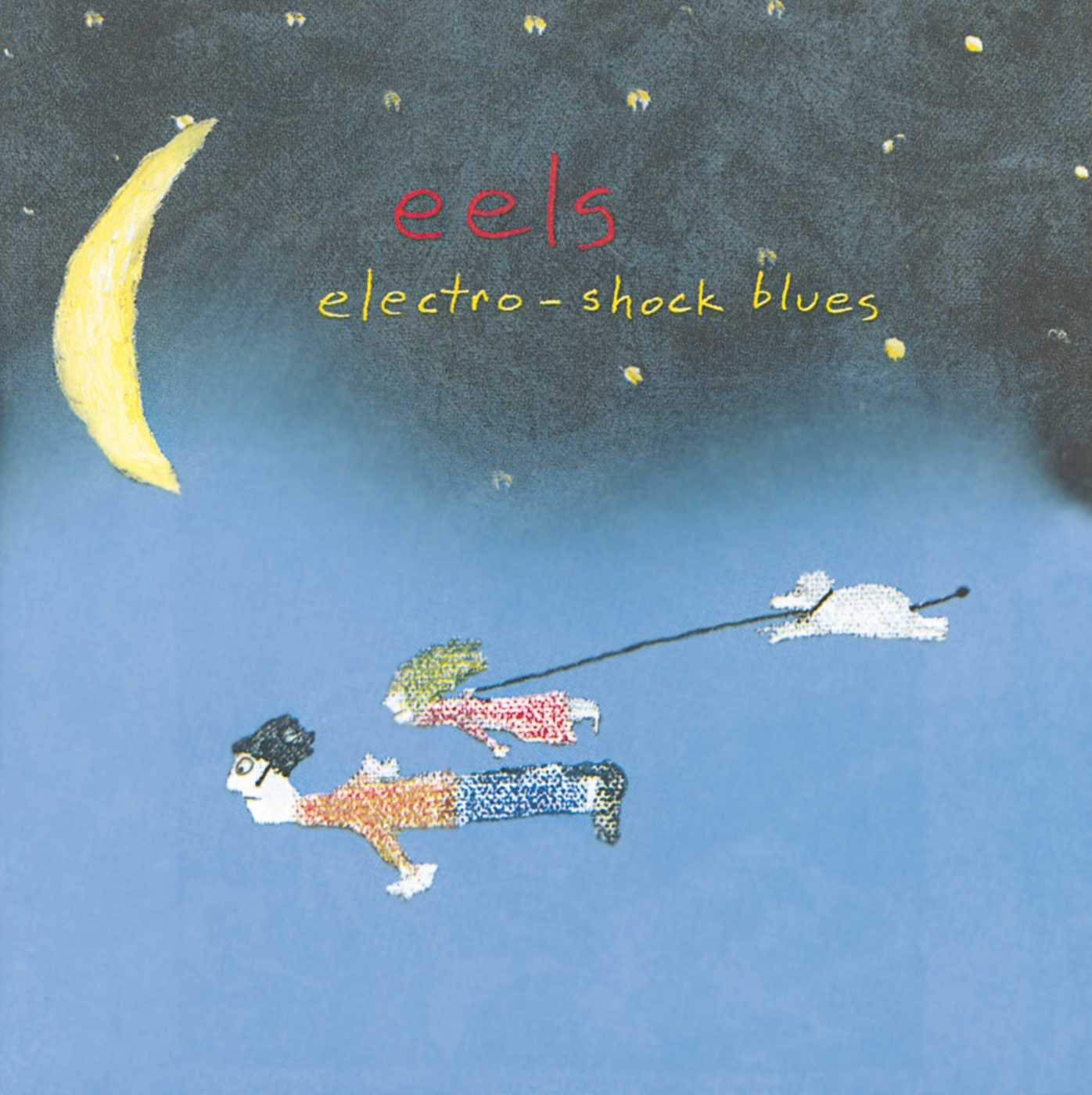

By 1998, this approach was starting to dry up, just as the music industry and mainstream radio were becoming consolidated. A few artists attempted to step up and show they were more than one-hit wonders. And, you know, good for them for trying. I know someone at my college newspaper reviewed Cake's Prolonging The Magic, but I don't know if I could name a song from it. But this Shampoo-like period before the gold rush ended did produce two masterpieces that don't tend to get their credit. The first was Local H, whose Pack Up The Cats was recently lionized, and the second was Eels' sophomore album Electro-Shock Blues, which turns 20 this Saturday.

By 1996, Mark Oliver Everett was finally getting everything he wanted. After a false start in which he released two albums working under the moniker E (both of which feature solid if at times cutesy songs drenched in seriously gaudy reverb), the songwriter hit gold with his new band Eels, launching the song "Novocaine For The Soul" straight to the top of the Alternative Charts in 1996. Inspired by Portishead and Nirvana, he'd come up with a sound that mixed post-grunge fuzz hooks with chopped-up soul and pop, and aided by producers Jon Brion and Michael Simpson of the Dust Brothers, Eels' debut Beautiful Freak, quintessentially '90s title and several dated elements aside, found him coming into his own and finally achieving some success. But as Everett wrote in his 2008 memoir Things The Grandchildren Should Know, he quickly tired of the machinations of the music industry, of performing for seas of "teenage jocks in backwards baseball caps."

Shortly after Freak was released, Everett's sister Elizabeth committed suicide. While touring for the album, his mom was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. Everett writes in Grandchildren about how he had difficult relationships with them both, how he struggled to understand his sister's mental illness, how she spent much of her life in and out of hospitals, how his mother never really recovered from the death of his emotionally distant father, the brilliant physicist Hugh Everett III, whose heart-attack-felled body Everett discovered as a teenager. He had gained the world and found it empty, and then lost everything. Disillusioned. An orphan. Alone.

In response, Everett looked death in the face and made the best album of his life.

The backstory of this album will always be the thing people think of first, but it is worth pausing here to focus just on how great this album sounds. Though Eels were originally intended as a three-piece guitar-rock outfit, it was here that it mutated into its status of "E, often but not always drummer Jonathan 'Butch' Norton and whoever else is around." Teaming up with producers and ranging again from Brion and Simpson to Lisa Germano and Grant Lee Philips, Everett created his warped version of slick Los Angeles studio pop, trying his hand at everything from mutated Tom Waits blues crawl ("Going To Your Funeral Part 1") to highly affecting, near-slowcore dirges (the title track), to barreling, cinematic depictions of despair (the strings "Cancer For The Cure" are near Hitchcock-ian in the dread they summon). The turntable scratches of single "Last Stop: This Town" are very of their time, but this song still gives a nice idea of what would have happened if, in the '90s, Beck had made a "funky Beck and sad Beck song" at the same time, though even Beck might not have had the chutzpah to have the single start with the line "you're dead/ but the world keeps spinning."

Everett proved himself to be uncommonly good at evoking the fear of seeing tragedy on the horizon and knowing there's no way to stop it, of creating the sound of feeling alone and anguished, of feeling like there's no reason to get out of bed but here you are anyway. But Electro-Shock Blues wouldn't have endured if it had only been about death. As Everett wrote, this was also an album about life, about acknowledging that on some level even those closest to us are utterly unknowable and we will lose them before we ever crack the mystery of human connection, and then someday we will be gone, but what other choice do we have than to go on? Electro-Shock Blues is filled with tiny, horrifying moments of empathy, where Everett tries to humanize his sister, zeroing on a passage from her hospital diary where she wrote "I'm not OK" ("Elizabeth On The Bathroom Floor"), illustrating her stay in the institution, confused but trying to hold on in "Climbing To The Moon." ("It's getting hard to tell where/ What I am ends/ and what they're making me begins.")

After so much loss (his mother would pass shortly after the album was released), Everett concludes the album with the most effecting and beautiful thing he would ever release, "P.S. You Rock My World," a sweeping ballad in which stumbles around his town, deals with the annoyances of the world and finds that for some reason, even a woman honking her horn at him makes him smile. At least he's still there to get honked at. "And I was thinkin' 'bout how everyone is dying/ And maybe it's time to live," he concludes.

And yes, said life-affirming song is called "P.S. You Rock My World," but the annoyingly '90s irony kitsch is just something you have to learn to deal with about this guy, a bad tic that infects this otherwise flawless album, from singing "Courtney needs love...and so do I" to "voices tell me/ I'm the shit" and that would go on shadow his career, from making an album under the name MC Honky that I still refuse to listen to and making a Missy Elliott cover that I am told is unlistenable. He's settled into a nice career as a cult artist with a devoted following, but I know that plenty of my peers still dismiss him as "fake Beck" or "fake Elliott Smith," probably because of these tendencies. But I always push back against that. He has two great albums (the 2000 follow-up Daisies Of The Galaxy is the spiritual sequel to Blues, the sound of opening back up to life) and plenty of other highlights, and during the last era when an oddball misanthropist like him would have the recording budget to dream big, he took a swing and made an indelible portrait of grief that, like its maker, continues to endure.

Listening to the album recently, I couldn't help but think of "Free Churro," the standout episode from the most recent season of Bojack Horseman, the most empathetic show on television. (Skip the next two sentences if you're not caught up.) In the episode Bojack (an anthropomorphic horse and actor riddled with shame and inadequacy) gives a monologue for the mother he never knew, every few moments stopping to ponder her final words "I see you" and whether she really meant it.

We all want that connection, but sometimes we don't get it in life. Sometimes you have to do it after the fact. In Grandchildren Everett writes of attending his sister's funeral, of seeing her face smeared in make-up she would have hated. In "Going to Your Funeral Part I," he looks at her coffin and marvels: "That was... that was once... that was once you." If he never really understood his sister and mom while they were alive, he did his best to understand them in song so he could properly say goodbye, so he could see them more one more time. Perhaps for the first time. And in the process, we saw Everett, finally and more clearly than ever.