"They told me that the classics never go out of style, but... they do, they do. Somehow, baby? I never thought that we do too."

Those are the first words spoken on Refused's The Shape Of Punk To Come -- which came out 20 years ago this Saturday, on October 27, 1998. Not even 30 seconds in, the album's already obsessed with its own historical significance: There's the brash prediction of the title, and the fatalism of the opening line. With the amount of time Refused spent contemplating the legacy of their most ambitious album on the actual album, it's no wonder that external debates about The Shape Of Punk To Come continue to rage on today, two decades after its release.

If we suspend disbelief and take that spoken-word intro to "Worms Of The Sense / Faculties Of The Skull" at face value, it would appear that Refused's "classic" started going "out of style" around six to eight years ago. Obviously, you can't calculate an actual decline in the number of bands taking cues from Shape's post-hardcore cocktail of punk, electronica, post-rock, and jazz. There was, however, a startling amount of critical backlash against the album published between 2010 and 2012.

Most likely in response to a highly touted 2010 Epitaph reissue of Shape, retrospective analyses popped up in Decibel, Impose, and MTV between those years. Just months after running a "making of" feature on the album, Decibel posted two anti-Shape takedowns within months of each other in 2011. The first was a "Justify Your Shitty Taste" column arguing that Refused's more traditionally hardcore preceding record, Song To Fan The Flames of Discontent, was superior to the one consisting of "a handful of solid riffs mired in a swamp of ostentatious Look at how we've evolved! Hardcore? Pshaw! showboating." The second, part of a series dedicated to arguing that certain general-consensus classics are "overrated as fuck," takes issue with the album's mimicry of early-'90s Dischord band Nation Of Ulysses. It claims that apart from Shape's "electronic frippery," the album was closer to "the shape of punk right then," rather than the future.

Impose's offering is the most decisive, proclaiming Shape "the single most overrated album to come out in the late '90s," and making some harsh value judgements about its influence: "Maybe you can rest easy knowing that at their best, Refused were simply a thinking person's Rage Against The Machine, and that right now, somewhere in Ohio, a bunch of Juggalos are wigging out to [Shape single "New Noise"] and thinking, 'Man, if only this band didn't break up, they could totally play the Gathering next year.'"

That cultural elitism carries over to MTV's "Why The Shape Of Punk To Come Was Wrong," published in 2012. The crux of that argument boils down to the album being "both light-years ahead of its time and entirely accessible to listeners who don't give a shit about sophistication and just want to scream along with a chorus." The writer then calls out Paramore, Fall Out Boy, New Found Glory, and seemingly every artist who ever played Warped Tour and/or signed to Fueled By Ramen, lamenting that so many artists "took [Refused's] lessons in the wrong way." The piece concludes, "A bunch of punk bands have covered 'New Noise,' but few of them actually made any."

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

In some ways, Shape is an easy target. Its title is tailor-made for dismissive rearranging, as the author of that MTV piece and dozens of snarky Twitter users have highlighted. Refused do wear their Nation of Ulysses worship on their sleeves -- not just by incorporating spoken word and jazz, but in their formal onstage attire, political jockeying, and similarly-titled songs. "New Noise" was a massive crossover hit, showing up as a regular fixture on MTV's Alternative Nation program, as a jock jam in the film adaptation of Friday Night Lights, and as a go-to cover for decidedly not-punk bands like Anthrax and (notoriously) Crazy Town. Following that initial 2010-12 wave of hit pieces, critiques of these aspects of the album started popping up (and still pop up) everywhere from concert previews, lists of overrated albums, and audio-nerd forums.

Value judgements made on the album's quality are one thing, but I've always taken issue with claims that Shape wasn't influential or important solely because they cribbed from Nation of Ulysses or because Crazy Town liked it. Does any of this negate the impact that The Shape Of Punk To Come has had on -- not just punk -- music as a whole in the past 20 years? The sheer number of musicians who have name-dropped Refused or Shape as an influence is staggering, enough to require a hyperlink-ridden "Legacy" section on the band's Wikipedia page. To get a better sense of modern context and range of Shape's cultural reach, I got in contact with 14 artists from all over the spectrum of punk, post-hardcore, metalcore, nu-metal, screamo, emo, folk punk, noise pop, and electronic music.

Refused folded shortly after The Shape Of Punk To Come's release, in the middle of a disastrous tour chronicled in 2006 mini-doc Refused Are Fucking Dead. Not many people came to see those disappointing shows.

Frank Turner, singer-songwriter, formerly of Million Dead: I was precisely the right demographic for The Shape Of Punk To Come. When it came out in '98 I was knee-deep into hardcore, but also starting to discover its limitations as a genre... I saw them on that [1998] tour in London and, though they only played about three songs, the show is seared into my memory.

Derek E. Miller, Sleigh Bells guitarist, formerly of Poison The Well: I first saw Refused in Vero Beach, Florida, in 1998, days before they broke up. I had no idea what I was hearing and seeing and strongly disliked The Shape Of Punk To Come when it came out. They looked and sounded so radical, my 16-year-old ears and eyes couldn't make sense of it.

Geoff Rickly, Thursday, United Nations vocalist: I heard it right when it first came out. A band playing our basement in New Brunswick said they had just played in Sweden and the locals, maybe Fireside, maybe Donuts had played it for them. I like Refused well enough but had "moved on" to stuff like Clikatat Ikatowi, Indian Summer, Reversal Of Man, Orchid, Swing Kids etc. etc. etc., so I was a bit dismissive. I may have said, "Oh yeah, ushering in the big Victory [Records] moshcore revival?" And they said, "You have no idea" and gave me a [dubbed] copy and it fucked me up. I didn't even know if I liked it or not. It was so different.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

The album didn't really pop off outside of punk circles like Rickly's until a few years after Refused's breakup, and it did so in ways that were wholly new in the nascent internet era. Author Byron Hawk devoted a large chunk of his recent scholarly book Resounding The Rhetorical: Composition As A Quasi-Object to explaining what was revolutionary about Shape's unorthodox rise to relevance.

Hawk writes, "Emerging technological changes both enhanced The Shape Of Punk To Come's distribution and reached its abundance of metaculture, which impacted the band's future in ways they couldn't have anticipated." In other words, turn-of-the-millennium methods like CD burning, peer-to-peer sharing, blog reviews, and MTV airplay became more important to the album's spread than it initial distribution. Hawk's take is jargon-y, but interesting: "All of these activities transform the album as single and intentional into a kind of coordinated performance among loosely connected actors and networks that, in turn, transforms both the work and its musical worlds, giving it more power as public rhetoric through self-organized poetic world making."

Dropping the highfalutin cultural critic-speak for a hot second, Hawk gives the big takeaway: "Refused said, 'Let the world sound like this,' and by 2004 many screamo bands did... Refused's cultural resonance, in part, made that musical world possible."

Jonah Bayer, United Nations guitarist: Refused were barely on my radar when The Shape Of Punk To Come was originally released in 1998, I just knew that they were European and had previously released an album on Victory Records. It's difficult to pinpoint exactly when the album started posthumously gaining popularity but I remember working at a music video program at my college television station in the early '00s and every time we showed the video for "New Noise," people would be like, "Who is this band?"

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Marcos Curiel, P.O.D. guitarist: I was watching Alternative Nation on MTV and their "New Noise" video popped on, and I was like, "Who is this?" It was extremely different than everything else being played.

Jeremy Bolm, Touché Amoré vocalist: My introduction to Refused was the "New Noise" music video. I remember seeing it on MTV in the very late hours of the night and thinking it was as if Blur was pissed. At least that's what the 14-year-old me took from it. I didn't own the album until several years later when I put it together that it was the same band from that music video.

Zachary Garren, Strawberry Girls guitarist, formerly of Dance Gavin Dance: I think I first heard about it around four years after it came out. I really liked the band Thrice, and they would post albums [online] that were influencing them at the time. That was one of the big albums they were always talking about, so I checked it out.

Chris Teti, The World Is A Beautiful Place & I Am No Longer Afraid To Die guitarist: I first got into Refused when I was 14 and heard "Liberation Frequency" on [Epitaph compilation] Punk-O-Rama Vol. 9... I remember getting in trouble during class for listening to the record on my iPod during high school.

Jordan Dreyer, La Dispute vocalist: I was 11 when the record came out, so it's not like we were sitting around at our record store eagerly anticipating them stocking the shelves anew, but by the time we were getting into punk around 15, 16, it was part of the zeitgeist. I don't remember a specific time that I heard Refused for the first time, but by the time we starting to make music, that record was omnipresent if you were into punk at all, because it was so course-altering for so many people.

Derek E. Miller: There was something that stuck with me, though, I kept listening and within two years they were one of my favorite bands.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

By the time the kids who were slowly discovering Shape started making music of their own in the 2000s, Refused's sound and ethos took on new life. There were obvious homages, such as Paramore's "Born For This," which lifted the hook from Shape song "Liberation Frequency," or Frank Turner's first band, named after a "The Apollo Programme Was A Hoax" lyric. But even more widespread were the many bands who took cues from Refused's stage presence, production techniques, album sequencing, and genre blending.

Dan Whitesides, the Used drummer, formerly of the New Transit Direction: After that album came out singers were dancing like James Brown on stage, guitars started sounding like guitars should sound, drummers were constantly playing that goddamn beat from "Protest Song '68" (I still play it) and I think bands just started caring a little more about how they sounded, what they were doing and what they were saying on stage.

Frank Turner: Refused came out with this insanely bold statement, and, against all the odds, succeeded in their stated mission, completely redefining the scene... I've probably listened to Shape more than any other punk or hardcore album, can play the whole thing and even was in a band named from one of their lyrics (Million Dead).

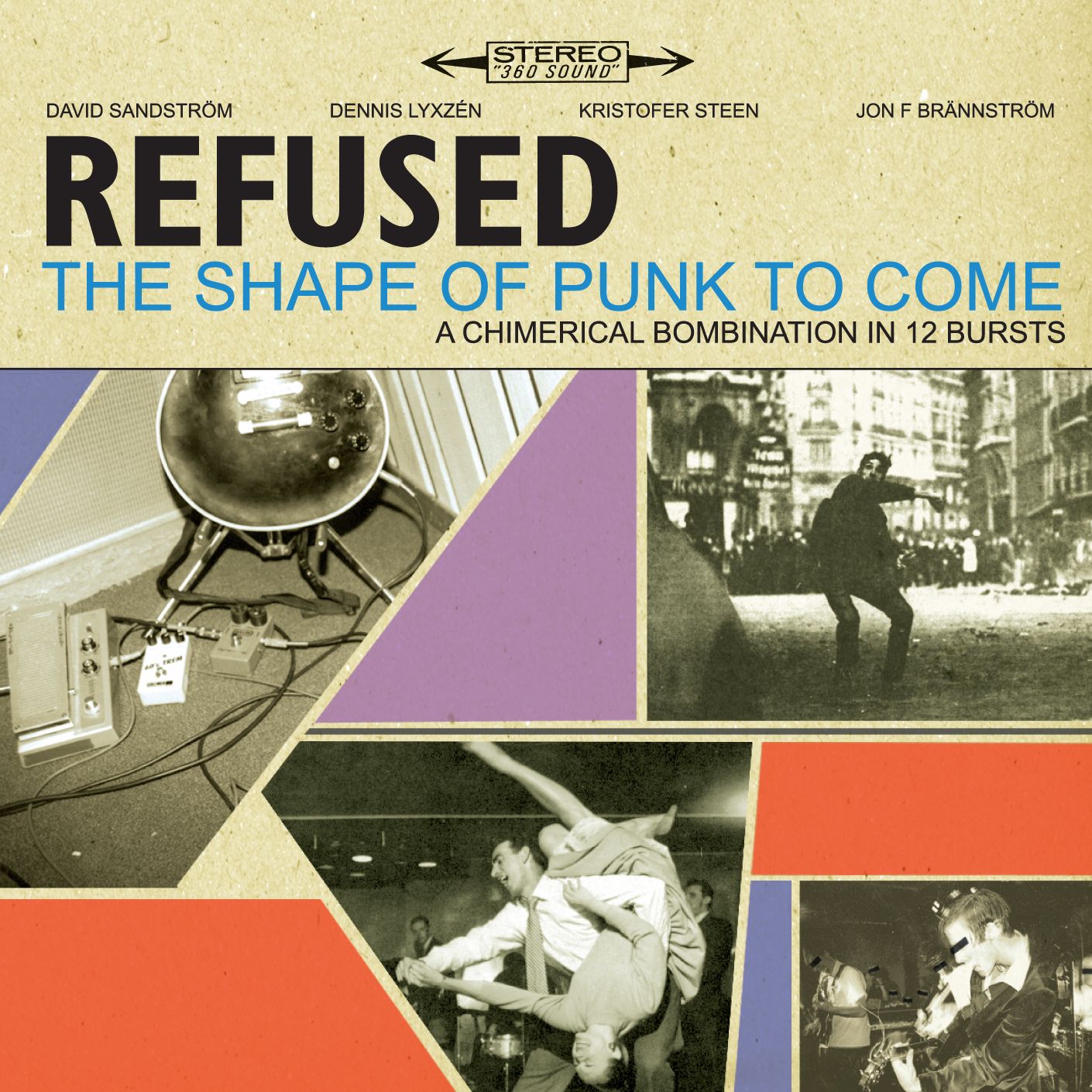

Derek E. Miller: They got everything right on that record: the songs, the performances, the flow, the spirit, the artwork and of course the production which is perfect thanks to Pelle Henricsson and Eskil Lovstrom, two charming sonic wizards I had the pleasure of working with in 2003/4 [on Poison The Well's You Come Before You]. I have to single out David Sandstrom's drumming -- some of the most explosive, dynamic grooves of that decade. Very inspiring.

Mike Shinoda, Linkin Park vocalist/guitarist: Coming up, while we were trying to define our band's musical style, I remember often referencing The Shape Of Punk To Come... And since then, many people, myself included, have tried to capture the same kind of intensity, craftsmanship, and imagination that album has.

The Bloody Beetroots: The Shape Of Punk To Come is a milestone in the history of music. The boys had the ability to project into the future an ideology that still resists nowadays. It must be used as an example for the new generations on how to structure and advance a strong and complete musical identity.

Marcos Curiel: The odd time signatures were very attractive to me as a guitarist, but it was just the overall energy, and the way they mixed electronic stuff with progressive metal and punk rock. That right there was, for me, badass. I mean, we do it, but we were grabbing from more of a hip-hop place. But that's always been in the back of my head when I'm writing -- "You know, that kinda Refused vibe."

Zachary Garren: It's definitely a very big influence on the kind of stuff I do. I like how they do really big riffs that aren't super technical, but are just really melodic and catchy, and they just stick with you and have a lot of energy. I also like the way they use contrasts, how they'll get really big and then really quiet, the way they bring in other genres to their sound. I like all that stuff. I think it keeps things interesting, and it's definitely something that I always try to keep in mind when I'm writing stuff.

Jordan Dreyer: The way it exists from beginning to end -- I think that was the big thing for us, hearing that record with all the interludes and transitional pieces, and incorporating different elements, and the sound recordings, that changed the breadth and scope of how you could conceive of a punk record... I think The Shape Of Punk To Come still stands up in that respect. I think that's something we took from it and still take from it, in a way. Also in referencing musical history and its own influences, I think that's another thing that we took at a pretty early age, to broaden the context of what's happening on our record.

Chris Teti: I think this album has greatly influenced records I've produced for other bands, and recorded with TWIABP. While it isn't something the band tried to recreate exactly, The Shape Of Punk To Come is a real masterclass on the importance of a well-sequenced record, disregarding any genre specific rules, a highly talented rhythm section, and using production to expand out fairly simple melodic lines... TWIABP has always pushed to make a whole album feel like a consecutive piece with specific transitions linking each track. The outlook is less on what can be a single, and rather how each song fits within the context of the record.

Geoff Rickly: It made me want a good sounding record, mostly. That was one of the biggest changes. A lot of bands were experimental -- Ink & Dagger had already introduced a lot of the excitement that was in Shape -- but the Refused record sounded like a million bucks. Nobody in hardcore was doing that.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

At a certain point, The Shape Of Punk To Come seemed to reach critical mass as an influence. Punk fans began to tire of bands citing the album as a touchstone in interviews, and bands began to tire of interviewers asking what they thought of the album. In a particularly hilarious example, Jordan Billie of post-hardcore contemporaries The Blood Brothers was once asked his opinion of people calling his band "Refused rip offs." He replied, "I didn't really know people called us Refused rip offs," continuing, "Our influences go a lot further than fucking Refused. Um, we weren't influenced in any way by Refused." It was an annoying question, but you can't blame PunkNews for asking him at a time when Shape was the punk inspiration du jour.

Jeremy Bolm: There are certain bands of the genre you just simply cannot take from without coming off as super obvious. Refused fall in line with bands like Converge, Coalesce, Botch, Dillinger Escape Plan, etc., in terms of having a specific sound and presentation that when a new band apes the sound, it's only met with comparisons.

Geoff Rickly: A lot of bands wanted to sound like Refused. For a long time. It's hard to say, the influence became so ubiquitous.

Jordan Dreyer: I think some of [Shape's contemporaries] sound like that era, and I don't think the Refused record does. I think it still sonically doesn't sound dated, that's probably a huge part of it too. With the technology with which we capture music changing so rapidly, everything sounds like an artifact of an era almost immediately, and The Shape Of Punk To Come... I don't know, it still sounds so good.

Zachary Garren: A lot of those other [post-hardcore] bands came out a little later, but even then, they weren't as progressive as Refused was at the time. Just the way they would incorporate electronic and jazzy stuff, I feel like that was almost taboo for punk/hardcore bands.

Chris Teti: On Shape, the drums are panned in weird ways like vintage records, the stand up bass sounds like it's from an old record, there's spoken word and techno parts, and it is always shifting from a lo-fi sound to modern flawlessly. There was much less genre blending from At The Drive-In, Blood Brothers and Glassjaw. While those bands have great/unique styles, their records they definitely stayed in their lane much more.

Justin Beck, Glassjaw guitarist, formerly of Sons Of Abraham: I was on tour with Shai Hulud with my other band and their guitarist was swearing how good it was, I gave it a listen while squatting in someone's basement and was like, "I liked 'em better when they sounded like a New Jersey band who'd play with Earth Crisis in a VFW."

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Certain punk lifers might not like the direction Refused took on Shape, or even more so, the direction taken by the artists who called Shape a primary influence. Are Linkin Park's Hybrid Theory or P.O.D.'s Satellite punk records? Of course not, but that doesn't lessen Refused's impact on their respective guitarists. Those albums are just as valuable to Shape's legacy as its artier, more niche successors like La Dispute's Somewhere At The Bottom Of The River Between Vega And Altair or Poison The Well's You Come Before You, if not more so, because of the exposure allowed by multi-platinum artists name-dropping a then-defunct Swedish band.

If anyone has a bone to pick (and, to borrow a phrase from "Worms Of The Sense," a few to break) with Refused, it's Nation Of Ulysses' Ian Svenonius. It's not just Shape that's drawn comparisons to his work, but also Refused vocalist Dennis Lyxzén's side project, the (International) Noise Conspiracy. Pitchfork's review of the band's debut album notes that only a few factors save the album "from being a total rehash of all your favorite Make-Up moments," the Make-Up being one of Svenonius' post-Ulysses bands. Svenonius declined to comment on Shape for this piece, but I would have been far more interested in hearing his take on Refused than anyone pissed off about the band's connection to nu-metal or bro-core.

Concerning "bros" for a moment, before I pass the mic back to musicians for the final word: as you've probably noticed by now, the musicians who supplied quotes for this piece are all men. I wanted to hear from Hayley Williams, who's said she's had to justify her Refused fandom to punks questioning Paramore's use of "Liberation Frequency," but she couldn't be reached. Several other female artists either declined to comment or were unresponsive. There's nothing inherently macho about the album -- lyrically, Refused didn't even come within sniffing distance of the chauvinistic territory of their emo contemporaries, instead expending the vast majority of their energy on critiquing capitalism. But for whatever reason, there's a problem with the actual shape of punk that Shape wrought: of the 26 artists listed as having cited Refused as an influence on that aforementioned "Legacy" section of Refused's wiki, Williams is the only woman.

The final question I posed to the artists who contributed to this piece was, "Was The Shape Of Punk To Come's title prescient, arrogant, or a little bit of both?" I think their responses sum things up nicely.

Derek E. Miller: They might say the title is tongue in cheek, but I'm willing to bet that they finished tracking and secretly felt like they had split the atom.

Dan Whitesides: The Shape Of Punk To Come was a game-changer, and to name your album that was fucking badass and completely true... I still love that album, I still listen to it and it still gives me the chills like it did when it first came out. It's timeless. I have a "Deadly Rhythm" tattoo, it's the only tribute to a band tattoo I've ever gotten and it'll probably be the last. The Shape Of Punk To Come is one of the best, if not the best, album to ever come out of all time ever and ever forever.

Timothy McTague, Underoath guitarist: The Shape Of Punk To Come is probably one of the top two most iconic heavy records to me -- [At the Drive-In's] Relationship Of Command being the other. Between the Refused and ATDI, I was shaped in such a wild way.

Mike Shinoda: When it came out, there was truly nothing like it... There's never really been anything else like it -- it's one of the truly unique albums, and one of my personal favorites of all time.

Marcos Curiel: For me personally, the title was the truth, because now, you hear it almost in everything -- the crossover of electronic, metal, and punk.

Jordan Dreyer: I never took the title as arrogant. I guess if they didn't back it up, maybe I'd feel differently. But it's like calling your shot and then fuckin' hitting a home run. If it was arrogant, it was justifiably so.

Geoff Rickly: [The title] was totally arrogant but also funny. When was punk going to sound like that? Will it ever?

Jeremy Bolm: The title... is an awesome nod to history and perfectly cocky to apply it to punk rock. Many artists wouldn't have the legacy they have without a dose or flood of arrogance, so when it comes to this album I'm all for it. It's been 20 years and I can't think of many bands that have gone as far outside the norms of a genre while still maintaining listenability and a message quite like this record. Title warranted.

Chris Teti: I think it's the most appropriately-named LP aside from Repeater by Fugazi. The title is bold, but can you name a record that pushed "punk" as tastefully or as well production wise? The record also starts with a seven-minute track... so I think I don't think they were making anything easy for the casual music fan.

Jonah Bayer: I think the fact that Refused broke up around the time of its release admittedly added a lot of mystique to the album, but that wouldn't have mattered if it wasn't so groundbreaking in the way it blended punk/hardcore conventions with electronic music, jazz and post-rock without sacrificing accessibility in the process. A testament to this is the fact that The Shape Of Punk To Come resonated with everyone from Crazy Town to Paramore, yet finds inspiration in artists ranging from Ornette Coleman to Born Against. I mean what other album on the planet can you say that about?