Fourteen minutes and 30 seconds into A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships, the 1975 almost grasp immortality. "Fucking in a car/ Shooting heroin/ Saying controversial things just for the hell of it," Matty Healy sings at the beginning of "Love It If We Made It." That's a hell of a way to open a song, and those lines in turn gesture at so much of what runs through the album as a whole. From there, "Love It If We Made It" flashes through fragments and punctuations that serve as Signs Of The Times. But in the beginning of the track, it's already a reintroduction to the 1975's gutsiness and a signal of the different headspace they occupy on their third full-length. Performative but actually-lived rockstar decadence of a seemingly extinct brand, generational self-destruction and self-medication, freedom and nihilism intertwined during a prologue for the end times: It's all in there.

The band positioned "Love It If We Made It" as the first official single from their new album -- despite the fact that "Give Yourself A Try" arrived a month and a half earlier, with a video and everything -- and it does function as an opening salvo for A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships. Growing ever more ambitious, the 1975 use their third album as a vehicle to wrestle with a collection of modern conditions at the same time as Healy strips back some of his past pretense to honestly reckon with addiction and mental illness. As we've come to expect from this band, there are a lot of ideas and directions at play on A Brief Inquiry, jostling together for prominence and coloring each other.

It's a bold move, in 2018, to announce an album called A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships and then steadily tease it over the course of six months and five singles. But the 1975 already have a reputation for boldness -- plus italics and underline while they're at it. You don't name your sophomore album something as preposterous as I like it when you sleep, for you are so beautiful yet so unaware of it if you aren't convinced of the grandeur of your own ideas. "There are no big bands who are doing anything as interesting as us right now," Healy proclaimed in a recent Billboard cover story. In 2016, I saw the band play at Lollapalooza and Healy walked onstage and introduced the set by declaring "Here's your new favorite band." This is not a group that believes in half measures.

There aren't many other young 20-something rock acts that could get away with it, either. But something changed when the 1975 released I like it when you sleep two years ago. Previously, they'd been a pleasant enough pop-rock band with simmering '80s inspirations lingering under the surface of their songs. Due to their young fanbase, they got sidelined as a boy band. Even in poptimist times, that's a particular lane, one the 1975 broke out of with I like it when you sleep. Suddenly, they were releasing a sprawling, tangled 70-plus minute album that veered from '80s art-funk to post-rock explorations to shoegaze-tinged meditations. That album announced the 1975 as very different artists, and it upended the critical narrative about this band, landing on end-of-year lists (like ours) and truly igniting the divisiveness that defines this group.

So much of the controversy around the 1975 comes down to the fact that people don't know how to deal with a guy like Matty Healy in 2018. A musician as self-aggrandizing as he is self-deprecating, who understands rockstar archetypes enough to deploy the ones we'd thought left behind while also claiming to be deconstructing the whole enterprise. For example: Healy's already been talking up the third album for a while, previously referring to it as Music For Cars. About a year ago he was walking around saying they they needed to make their OK Computer or The Queen Is Dead: the third outing that forges ahead into new territory nobody could have expected, the masterpiece that begins to solidify an artist's legacy. Which, depending on how you take that, means the 1975 were either acutely aware of the pressure to solidify the goodwill turnaround of I like it when you sleep, or they are excruciatingly conscious of the pantheon and their efforts to join it, or they are willfully trolling their critics.

Nevertheless, nearly two decades into the 21st century, it is exceedingly uncommon to come across a rock band that isn't resigned to a smaller slice of the world, to find a rock frontman who's still naïve or visionary enough to aim for nothing short of domination, of being the voice of an era. In this case, the facets that make detractors roll their eyes in dismissal and disgust are the same ones that engender adoration and fascination in others, those that might view the 1975 as a breath of fresh air in an era in which so many of our primary rock bands are more genteel. Adam Granduciel's matter-of-fact everyman aura fits the hazy highway dreams of the War On Drugs, just as St. Vincent's ever-increasingly controlled persona parallels the pop-art manipulations of her work. But Healy is a rare breed these days.

When the 1975 started trafficking in squirmy, lust-driven grooves that earned them comparisons to '80s pop acts like Scritti Politti, Duran Duran, and INXS, the latter in particular stood out; Healy had the kind of swaggering, preening presence of Michael Hutchence. And he knew he did. "I do the Jim Morrison thing a bit," he said in that same Billboard story. "But I know that you know that I know that this isn't real." In that sense, he's a new breed entirely: a throwback to frontmen of the past, possessed and charismatic and flawed and unafraid to be gauche, to embrace the inherent ridiculousness of his role. And yet, also self-aware and paralyzed by history, messy in his efforts to exist in relation to that and in relation to his surroundings today.

Healy's actually spent much of the press tour behind A Brief Inquiry getting pretty real. Having checked himself into rehab to kick a heroin habit, he's been hyper-conscious about the kind of rockstar signaling he was playing into in the past. He's been walking around saying his goal is to be sincere, to brush away all the self-reflexivity and make something truer than before. And the 1975's new album is that, with many quiet and personal moments blended into its big idea pillars. But it is also a continuation and expansion of everything people have come to love and hate about this band in recent years. It doesn't have the same runaway energy, the same sense of discovery, as I like it when you sleep. It ventures further out in every conceivable direction, takes on even more, and comes out a more beleaguered finished product in both its personal and thematic contexts.

Even with this being the 1975, an album titled A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships arrives with its own type of baggage. That is not a cipher that leaves you curious about what may lie ahead, the way that I like it when you sleep's blatantly ludicrous nature actually cleaned the slate of any pre-conceived expectations of what the 1975 were or could be. A Brief Inquiry, rather, is a name that immediately tells the listener that Things Will Be Addressed here. As you might expect, A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships is neither brief, nor limited to its titular topic, even if the topic in question is a particularly thorny and multi-facted one. Instead, the album reaches more forcefully for greatness than I like it when you sleep, losing some of the joy that characterized their 2016 output. There were plenty of heavy topics on I like it when you sleep, but A Brief Inquiry takes on so much from so many different angles that it makes its predecessor seem cohesive in comparison.

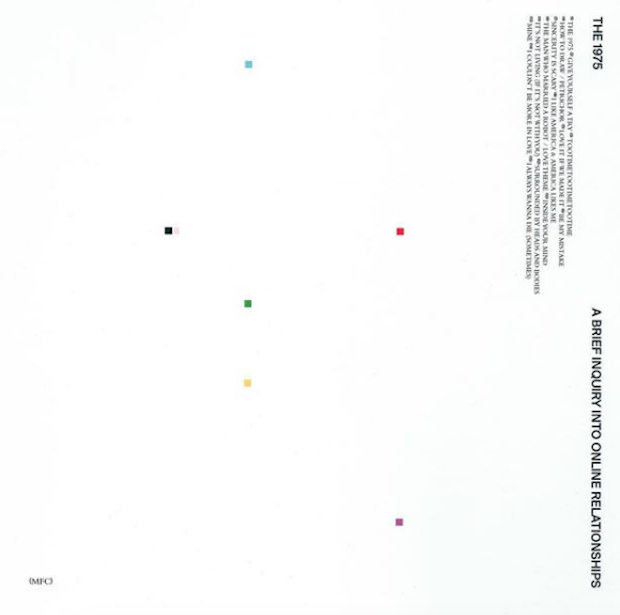

A Brief Inquiry is 15 tracks zigging and zagging wildly across an hour. If we thought I like it when you sleep took a lot of surprising left turns, the band's restlessness or adventurousness feels multiplied on A Brief Inquiry. There are barely two songs on the album that seem to exist on the same aesthetic wavelength. There is house-inflected pop on "TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME," glitchy Radiohead detours led by Bon Iver voice warping on "How To Draw / Petrichor," straightforward acoustic balladry on "Be My Mistake," the squiggly horns and gospel choruses of a Chance The Rapper track on "Sincerity Is Scary," the garbled satellite transmission of a pop single in "I Like America & America Likes Me," a Siri-delivered spoken word interstitial about a man falling in love with the internet on "The Man Who Married A Robot / Love Theme," and particular whiplash in the album's final stretch when you get to a swing ballad in "Mine" and a sweeping, lachrymose post-Britpop anthem in closer "I Always Wanna Die (Sometimes)," cavernous atmospherics and strings and all.

This is music made by and for people raised on having everything all at once, resulting in a dizzying grab-bag approach in which an artist doesn't bother to constrain their impulses. The creative freedom the 1975 clearly feel is often intoxicating enough on its own, when you never know what lies around the next corner on A Brief Inquiry. And, implausibly, the more you listen to the album the more it does hang together as a complete work despite the wide array of sounds and directions present in those 15 tracks. Somehow, the whole thing does feel like the world of A Brief Inquiry Into Relationships by the end.

That isn't to say the album is totally consistent. There are certain things that the 1975 just excel at more so than others. The singles are by far the strongest tracks on A Brief Inquiry, particularly "Love It If We Made It" and "It's Not Living (If It's Not With You)," both of which still quote those '80s influences while blowing out into epic, contemporary rock songs. These classic pop touchstones still serve the 1975 best, as on slow jam "I Couldn't Be More In Love." Occasionally, they fold more recent styles in successfully as well, such as in the effervescent earworm "TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME."

But while there are no abject failures on the album, there are some moments where you could start to wish the 1975 began to rein it in. A swing ballad, a skittering electronica experiment -- these turn out not to be the best look for this band. When the 1975 released I like it when you sleep, all the talk of their genre agnosticism was rooted in the novelty of it, a supposed boy band throwing several curveballs in a row. That novelty has worn off by A Brief Inquiry, an album where those of us who became adherents with the 1975's sophomore effort are waiting to see if they could make good on that promise, if that was just a fluke last time.

The diversity of I like it when you sleep also had that John Hughes throughline, synth-pop ballads and robotic Bowie gyrations co-existing and anchoring the album's more severe departures. A Brief Inquiry gives you no connective tissue, no trail; it is as disorienting as the topics it sets out to address. As with many aspects of the 1975, their strengths and weaknesses are often the same, just reliant on how the dice roll that particular day. Their fearlessness and malleability here occasionally bump into a more scattered disposition. A Brief Inquiry has the bizarre quality of bearing a legible arc while also feeling all over the place, leaving you unsure whether that latter characteristic is crucial to the album's narrative or whether it was intentional or not.

Similarly, the 1975 have often oscillated between true cleverness and moments where they think they're being clever, and A Brief Inquiry achieves actual profundity as often as attempts at such fall flat. There's no better example of this than "The Man Who Married A Robot," which holds both outcomes within a single track. In it, we hear the story of a lonely man who falls in love with the internet, his true best friend; much of it plays like a cliché allegory we've heard before about our relationship to technology. But there are lines that cut through, like the clinical way in which the narration describes the man getting sad, and his friend the internet cheering him up by bringing him "cooked animals and show[ing] him the people having sex again." After the man dies, there's an abrupt ellipsis stating "You can go on his Facebook ... " that turns the whole track upside down. It's not just an epitaph but also an advertisement, and recalls an eerie feeling for anyone who's received a notification from a dead person's digital remains on a social media platform.

Still, tracks like "The Man Who Married A Robot" will do little to sway people who have found the 1975 to be cloying and/or pretentious. You can't blame them entirely: It often seems to be a double-edged sword, embracing digital culture yet also trying to grapple with, or lightly critique, or make sense of its seismic cultural shifts. It feels played-out even as it feels as if we've barely scratched the surface, have barely acknowledged just how vastly this could be remaking civilization socially and psychologically. Things are moving too fast for us to comprehend them in real time, and yet that also means some art attempting to do so feels trite upon arrival.

The 1975 are better-equipped than others. If you compare A Brief Inquiry to something like Arcade Fire's hectoring Everything Now, it at least comes across like a more nuanced attempt to engage with these issues, from young people who have grown up alongside these changes. This, too, is something the band is aware of. "We all know how addictive the phone is, but when it’s brought up, it’s boring," Healy told Billboard. "It’s almost like Brexit or Trump now: 'We know, Granddad, we know!' But we don’t really want to do anything to change it."

Really, more so than with any musical or lyrical decision on the album, the 1975 might just be getting in their own way with the name A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships. The title is somewhat of a misnomer, with the content of the album really skewing more towards a treatise on modern love and how the hell we are going to take care of ourselves. There's (thankfully) no exegesis on Tinder or what it means when an estranged ex keeps liking your Instagrams years later. There are tracks like "TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME," which uses texting and hints of infidelity and jealousy to create an infectious, number-based hook. Several songs, from "Inside Your Mind" to "I Couldn't Be More In Love," touch on the unknowability of other people and the impossibility of truly understanding another person's mind no matter how close you are -- an inherent, recurring reality but one exacerbated by all our personal refractions online.

There is a poignance to it, when the 1975 dance between little snapshots of how people live and Healy's own demons bared, damaged romances both chemical and personal. Maybe all the experimentations will work for various listeners; there are a lot of versions of the 1975 on display on this album, and people will appreciate a series of them based on their own predilections. But it's hard to walk away and not feel that the 1975 are at their best when they are taking this massive churn of ideas and propelling them forward in bombastic, gleaming pop songs, songs big enough for Healy's personality to sell the concepts therein.

This isn't intended to restrict the 1975 to one thing they are supposed to be, especially not after years of them imploding categorizations. But consider how the frazzled riff of "Give Yourself A Try" allows Healy to reintroduce himself; the first proper song on the album, it's a frenzied word torrent addressing Healy aging, his life changing, people's perceptions of him, what he's become. Consider the sickly-sweet pop of "It's Not Living (If It's Not With You)," in which Healy delivers an ode to heroin conflicted between memories of euphoria and the realities of self-annihilation. (One wishes a song titled "I Like America & America Likes Me" was as big and glittering and contradictory.) Consider the scope of "I Always Wanna Die (Sometimes)," a towering finale full of cinematic melancholy. And, of course, consider "Love It If We Made It."

There's something to be said for how somber A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships turned out in the end, how whispered and fragile it is amidst all the noise. But the reason people get behind the 1975 because of their posturing, because of their insistence on becoming the best and most brilliant, is because they are one of those bands that occasionally shows you how that could very well happen. They are one of the bands that do seem like they have that capability. "Love It If We Made It" is the best song they've released yet, a keystone for A Brief Inquiry that unfortunately can't be lived up to elsewhere on the album. Because they already got it perfect here.

When "Love It If We Made It" arrived this summer, some people (including Japanese Breakfast's Michelle Zauner) quickly referred to it as "This generation's 'We Didn't Start The Fire.'" And while the 1975 don't quite go all-in on the historical laundry list approach of Billy Joel's famous '80s hit, they do approximate it for modern times. Black Lives Matter, Lil Peep's death (and thus the opioid crisis), Kanye, fake news -- all this is colliding in "Love It If We Made It," often in ways as illogical as real life. The song is huge, blaring out sardonic-yet-desperate readings of lines like "Fuck your feelings!" and "Truth is only hearsay!" From a band that is a lot, on an album that is a lot, "Love It If We Made It" is ... a lot. We knew this going in, after the 1975 sent out a snail mail press preview that all these topics would be covered in their new single. But nobody thought it could be quite this transcendent.

Throughout the album, Healy sheds skins and voices impressively. But he's at his most transfixing here, with a ragged true-rockstar howl cataloguing our times via the soundbite detritus that often clouds out the real crises of the day. The moment where, after the song quiets down, it roars back in with Healy spitting out Trump's infamous quote of "I moved on her like a bitch!" -- that's when you realize this guy's star power. And the rest of the song is where you recognize what this band can really do.

From there, from all this darkness and experiential fog captured in "Love It If We Made It," Healy yells "Modernity has failed us/ And I'd love it if we made it." There, the band break into the kind of stratospheric chorus they neglect too often on A Brief Inquiry. It's a very fractured kind of hope, settling for "I'd love it if we made it." But Healy locates a truth of millennial experience in this song that flickers in and out of view elsewhere on the album. Modernity has failed us, the refrain for a generation that has learned to live as if the floor might fall out from under us at any given moment.

The 1975 might be absurd, but growing up as a millennial has also often been absurd. This is a generation that was raised in the seeming halcyon days of the '90s. The Cold War was over, 9/11 hadn't happened. History seemed to be progressing teleologically into a bright technologically-advanced future. This same generation inherited the War On Terror, a global recession, collapsing industries, the rapidly approaching threat of catastrophic climate change, and society on the brink of eroding as people retreat into fictions and xenophobia. Through it all, we are 10 or 15 or 20 years into our new digitally-dominated lives and we still have no real bearing on its psychological impact, the ability to numb yourself by scrolling through an endless Twitter feed featuring all the world's ills and impending disasters, over and over and over.

That's what "Love It If We Made It," and much of the rest of A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships, is really depicting. The static, the paralysis, the disenchantment, the fury, the dislocation, produced by a world that seems to be falling apart and the way the internet brings that right up to our faces constantly. The way we struggle to still relate to and communicate with one another through the suffocating rush of distraction and information alike.

Without the same amount of endorphin-inducing highs as its predecessor, A Brief Inquiry perhaps marks a moment where the 1975 take on a bit too much, even for them. But that, conversely, makes it work in its own way. The fact that the album never sits still and yet sounds so weathered makes it all the more effective a document of life in 2018 -- sometimes messy, sometimes genius, sometimes questionable, it's the soundtrack for all of our muddled attempts to figure our shit out. In both their glib observations or their resonant couplets, the 1975 here come across like poet laureates for a lost and scrambled generation.

Whether people like it or not, there's a real chance the 1975 are on track to be one of the defining names of the decade, a real chance they have a true generation-defining classic in them. There is a noble cause in their work so far, a young band not looking back as they careen headlong into all kinds of treacherous territory. That's what makes the 1975 what they are, what makes them worth paying attention to as they mutate and try and find their way to the next sound. Because somewhere within this band, there is something that is indeed very in tune with our times.