Damon McMahon on his breakthrough Freedom and what's next

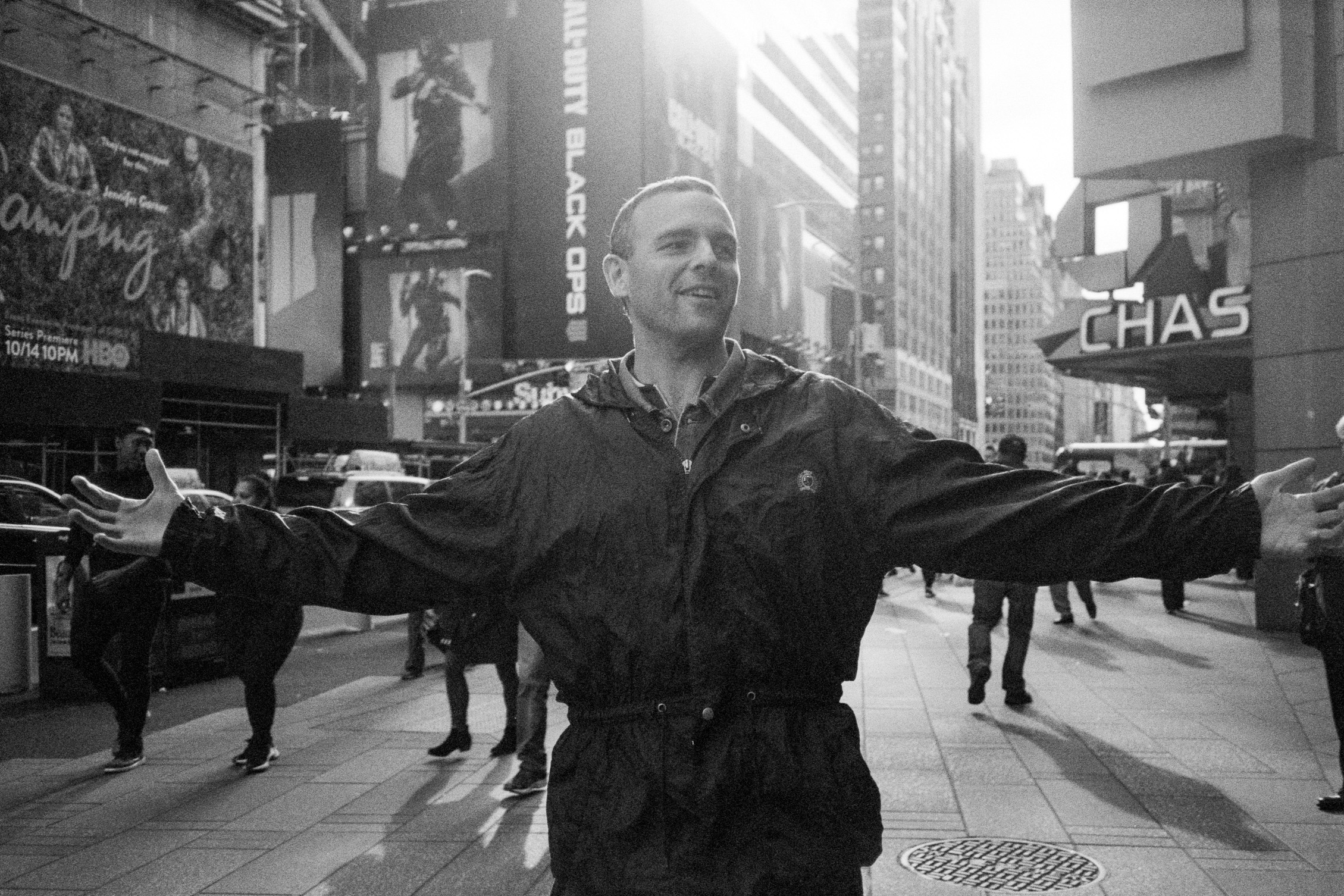

When someone says they want to show you a piece of Old New York, there are certain locations you might imagine. Maybe a far-flung corner of Brooklyn or Queens, less touched by waves of gentrification. Perhaps one street hidden away in the long-lost stretches of the Lower East Side, still openly marked by all the neighborhood's history. Or maybe there's just that one stubborn dive bar, resilient in the face of whatever neighborhood's decades-long shape-shifting. Plenty of New Yorkers have their own version of the old, real city. But more often than not, your first guess wouldn't be down the block from Times Square.

That's where Damon McMahon wants to meet. There's a place on 38th street, off 7th avenue, called Ben's Kosher Delicatessen -- a cavernous Jewish deli untouched by the tourist- and family-friendly sheen of today's Times Square, in the shadows of and yet unrelated to the towering corporate offices that flank the area. We sit down for lunch, both of us conspicuously young compared to much of the restaurant's mid-afternoon clientele. And McMahon begins to explain.

"This is the last vestige of old New York," he says of the area, from the edge of Times Square to the streets surrounding Port Authority. "One of the only places that still feels like [the New York I remember from the '90s]. New York was dirty and rough and aggressive. It was like a mid-sized city. Even though I was half living here, I was instantly an outsider. No one was from outside, the kids were born and raised."

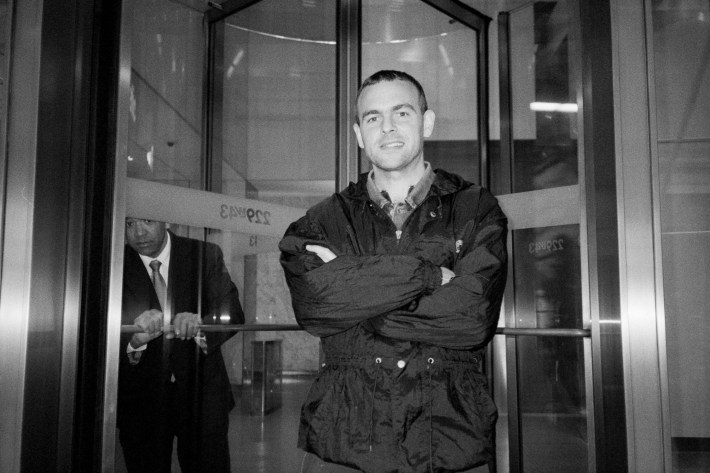

On the afternoon McMahon and I meet, he is just about a week away from leaving New York, about to make that cross-country sojourn to relocate in Los Angeles, like so many other New Yorkers in recent years. Like so many East Coast natives lured by the mythology of the other side. There is little of McMahon's demeanor, in general, that would ever suggest nostalgia. But if he's about to say goodbye, it seems appropriate enough to go back to his roots. And as much as Freedom, his new album under the moniker Amen Dunes, has initiated a new chapter for him this year, it also seems to simultaneously be about shedding the past in all forms.

Before we have a chance to dig into McMahon's latest work and how things have changed in the wake of its release, we have the sort of quintessential New York experience McMahon remembers, one more time to send him off to the West Coast. Our waiter at Ben's is middle-aged, eccentric or maybe drunk. He rolls his eyes and balks at McMahon requesting a canned soda, because fountain drinks come with free refills. He acts like I kicked his dog when I ask for mayo, and tells me to put away my "homework" when he sees my phone recording on the table. "Deli humor," he grunts at some point. "You gotta have deli humor to survive 34 years of this." He's the sort of character that, if you're a certain generation of New York transplant, you've seen more of in Seinfeld than, say, in the eateries of Williamsburg.

In between periodically being chastised, McMahon and I do have a chance to unpack Freedom and the year Amen Dunes has had. Though the project always had a cultish following, and started to gain more momentum with the beloved 2014 collection Love, Freedom has become a clear turning point. Never before has an Amen Dunes album elicited the kind of fervent acclaim as Freedom, with McMahon being profiled in a wide array of publications over the course of 2018 while his album was touted as one of the year's finest. Five full-lengths and a smattering of EPs in, Amen Dunes is now a breakout act, one of the indie names that have defined 2018.

It was a long road to this point. At 38, McMahon has been making music for 16 years. He began the '00s with another band called Inouk, and then ended them by reemerging as Amen Dunes. In earlier iterations, McMacon presented himself as a long-haired weirdo crafting shadowy, druggy psych-folk and rock. Over the course of this decade, he's gradually transformed, bringing the project more and more into focus.

Part of why people latched onto Love is it still had that Amen Dunes haze, but McMahon's pop sensibility was starting to creep closer to the surface. Freedom is a fuller realization of that, subtly mixing dusty classic rock-isms and electronic textures, slyly colliding the slow-rolling discovery of a weary American highway album with the edge of a more urbane set of compositions. Leaning harder on old-school influences, Freedom has the fried swagger of the Stones, the rambling street poet disposition of Dylan, the everyman scenes of Petty, the scope of Springsteen.

Today, McMahon looks more like his old New York-based family members might have -- hair hewn close to his head, often sporting just an undershirt onstage or in press photos. Leading up to this version of McMahon, and to Freedom, was a few separate lives, some vagabond years. In his youth, McMahon lived in suburban Connecticut but would head down to the city; this being the '90s, they were fallow days for New York's rock scene, and McMahon's formative experiences actually happened at illegal raves a kid could get into. He moved here, grew into the burgeoning rock renaissance. But before Amen Dunes took shape, he also looked further afield, resulting in a late 20s stint in Beijing years after a LSD phase had sparked a fascination with Daoism.

The mixture of these experiences results in a curious character: McMahon is half matter-of-fact/no-bullshit talk and half psychedelic musings, wisps of thoughts hard to ground in words exchanged between two people over deli sandwiches. For example, a simple question about the music McMahon gravitates to, or the contemporary music he doesn't, results in him calling himself non-partisan, which in turn spirals out into this: "I feel non-partisan to planet Earth. I don't feel an allegiance to my species."

Songwriting can, of course, be an elusive process, and talking about it can be that much more obscured. While Freedom made its presence known in 2018, McMahon's relationship to his music becomes more complicated once it's out in the world. "If anything, it just gets further and further away," he says. "I feel disinterest, almost, in the record." He remarks that Freedom's title track is the main song he still feels a deep connection to. As for the others: "I don't understand them anymore."

This isn't to say McMahon dislikes everything he's done as Amen Dunes after the fact -- quite the opposite. Rather, it's just that the work, and the reasons behind it, become more enigmatic to him as time passes. "I don't feel connected to the doer," he explains. "When people message me, I'm like, 'I don't know who you're talking about.' I'm like a bystander. It's done, it's passed me by, it's left its stamp on me and this disc and this digital file."

McMahon far prefers recording to touring for this reason. It's the repetition, the constant performance of the songs, that brings him further away. When one album's done, he's thinking about the next, dreading the uphill battle of making these things but also yearning for the shock of lightning, of inspiration, that comes in the writing and recording process. "It's really for that moment of discovery," he says. "You're like an archaeologist digging. The hunt is super exciting."

"Being a songwriter, it's not a hobby, it's not for fun," he says at another point. "I'm not choosing to do it. I'd rather not be doing it, in a way." When you combine sentiments like that with McMahon's comments about moving on from his past work, you might might imagine a guy who spent a little too long in the trenches before getting his due recognition, a guy who was half-ready to move on. But with McMahon it's more a question of intent and personality. He feels very "alone in music-making," unlikely to socialize with many other musicians, unable to relate to the usual reasons so many pursue that life.

"Good music is spiritual," he ventures. "Good music is undirected. It's felt and received. It's almost natural. Musicians who are on that tip, they make music because they like to connect to the fucking ether." That's what he's setting out to do each time, setting out to channel, setting out to experience in writing. And as he moves on from one album to the next hunt, he remains grateful he went through that at all, to create a finished document that will theoretically last beyond him. That classic artistic drive, to leave dozens of little pieces of yourself behind, destined to endure but also rejoin the ether from which they came, fragments of one person in a backlog of art and history.

With all these months to process Freedom and people's reactions to it, perhaps that's why the conversation gets more philosophical, abstract, trippy. But it also relates back to McMahon's initial goal with the album. These songs were angling to observe different assumptions about himself and his identity, to then perhaps discard them. "Miki Dora" took on ideas of masculinity, the totemic "Believe" grappled with his mother's illness, and various songs trace other aspects of McMahon's familial lineage and his experiences in New York. Beyond the fact that Amen Dunes is now a more prominent name in today's rock landscape, the process seemed to work: It did birth a new version of McMahon by way of exorcism and memory.

Because of its languid rhythms and sun-drenched atmospherics, Freedom can feel like an LA album, as if McMahon's new home was calling him via the sounds he was making. (He did partially record it there, but more importantly the way the guitars unspool often sounds like smoke dissipating into LA's endless sky, or like aimless cruises through radically different Southern California landscapes.) McMahon counters that Freedom is a New York album, and deeply so. "It sounds like New York, it's about New York kids," he argues. "The attitude of it, what it's talking about, that voice on that record -- that attitude and vibe feels like New York feels." The fact that the album ends with a song called "LA" is almost a feint, too, with McMahon calling it a "misnomer" about the fantasy of LA rather than the place itself.

After we finish at Ben's, McMahon wants to take a walk up 8th Ave. We pass by Port Authority, we make our way uptown. Though it's a very, very far cry from the seedy version of this area currently depicted on The Deuce, McMahon has a point about some remnants of New York's old grit lingering, unable to be swept away from this part of town. At one point he stops and points to a nondescript loading door, noting that it's where Inouk and lots of other bands (including the Strokes) actually used to practice "before Williamsburg became a thing." The bodega downstairs used to let them come in and grill their own sandwiches during breaks. "This is the most interesting neighborhood," McMahon repeats. "The last bastion of old New York."

There is still no wistfulness in McMahon's voice -- he's been trying to leave New York for years already, but it wasn't possible until now. After his mother passed away amidst Amen Dunes' summer tours, McMahon lost his last, significant connection to the city and its surrounding areas. "Nah, everyone's dead," he says bluntly when I ask if he still has roots here. He has no tangible history now, just literal ghosts to mingle with the echoes of the place he remembers from decades ago. I ask if, in hindsight, the search for a new self through Freedom may have doubled as a goodbye to this place, to everything he built here, as he turned his eyes toward the horizon. "Maybe subconsciously," he drifts off.

Perhaps that's why Freedom reached so many new listeners, perhaps that's why it struck some as an instant classic when so much of Amen Dunes' other output went unnoticed. McMahon's the first to admit that he's still trying to wrap his head around so many more people embracing his music suddenly this year, but he's also the first to admit that he had expected and hoped for it a long time ago. After all these years, he recognizes that while he always "considered it pop music," it was partially hidden. Buried. Maybe released the wrong way, too. It may have taken over a decade, but Freedom is a more open album. Not just sonically, not just emotionally -- but you are getting an album that documents snapshots of a person's inherited history, and their effort to redirect those facets towards a new future.

At the same time as Freedom's nakedness made it relatable and immersive, it is not necessarily something McMahon plans to repeat for the next one. "This album has led me to a very pure sense of what I need for myself from the next album," he says. "I'm interested in even less of myself in the music, more privacy. You're only occasionally really heard directly. If you get really personal you have to be prepared to have yourself not heard. That's really difficult."

He's also thinking about what Amen Dunes looks like from here musically. While a breakthrough like Freedom might usually compel an artist, or the mechanisms surrounding them, to explore touring endlessly and milk the album cycle, McMahon's management is encouraging him to follow Freedom quicker than he did Love. And he's got a plan for that. "I have very explicit stylistic ideas," he says. "It's pushing [the mix of electronics and rock on] Freedom way further. I'd like to make it very colorful and visceral." He's actually plotted out the next four albums, "in broadstrokes." The one after Freedom's successor "couldn't be more different."

When Freedom made it's way out into the world, it introduced a new version of McMahon, to existing fans and newcomers alike. Whenever those new albums arrive, and in whatever form they take, those too will diverge. They will be from a man with a few more years, living in a new place, untethered to the city and family and scene that first sculpted him. A man that was already prone to searching and wandering, and who's starting the process over again one more time, across a country. After the 2018 that Amen Dunes had, far more people will be waiting to see what comes next than in the past. And next time, all of us will be meeting a new version of Damon McMahon once more.