In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

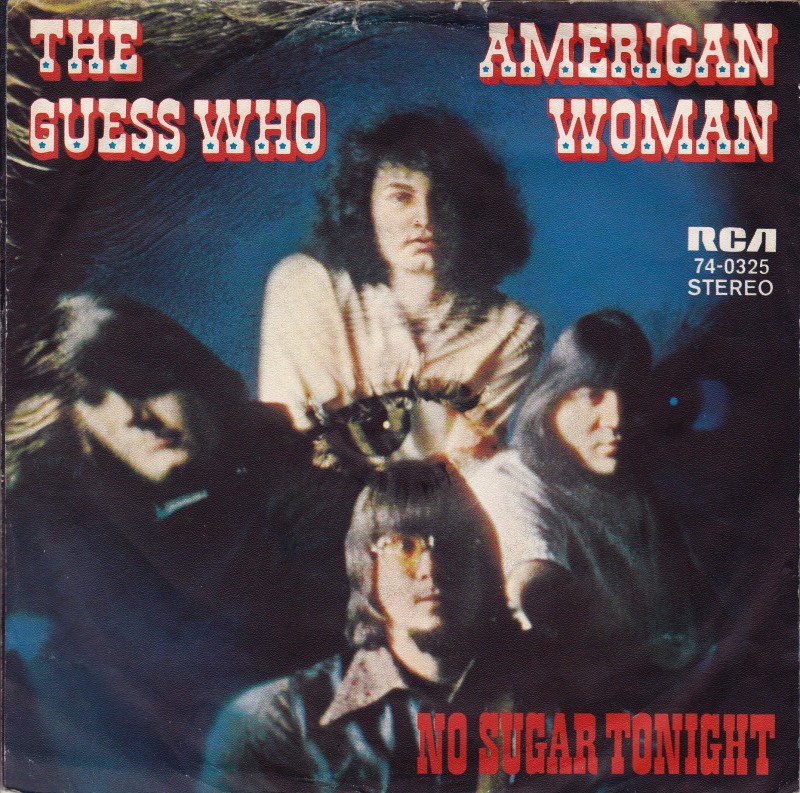

The Guess Who - "American Woman"

HIT #1: May 9, 1970

STAYED AT #1: 3 weeks

Led Zeppelin never got any higher than #4. ("Whole Lotta Love," 1970, would've been a 10.) Deep Purple got to #4 twice, but they never got any higher. ("Hush," 1968, a 9, and "Smoke On The Water," 1973, an 8.) Black Sabbath peaked at #52. ("Iron Man," 1972.) AC/DC's highest-charting single got to #23. ("Moneytalks," 1990.) Judas Priest charted on the Hot 100 exactly once, and that one only got to #67. ("You've Got Another Thing Comin'," 1982.) Iron Maiden never made the Hot 100 at all. Neither did Motörhead. Metallica once made it as high as #10. ("Until It Sleeps," 1996, a 7.) Even Aerosmith, the most commercially shameless of the iconic hard rock bands, only got to #1 once, and that was with a Diane Warren power ballad from a blockbuster disaster movie, decades after their creative peak had ended.

For almost the entire history of hard rock, the genre has had a hell of a time getting to #1 on the Hot 100. (There have been two historical exceptions: The glam-metal late '80s and the post-grunge late '90s/early '00s.) All the bands in the preceding paragraph have been vastly popular. They've toured arenas, or even stadiums, and they've sold millions upon millions of albums. But they've never been singles acts, and radio has historically shied away from them. So what makes the Guess Who's "American Woman" so special? Why did that song hit #1 when so many others fell short?

There's no one reason why "American Woman" landed the way it did. The song certainly hit the anti-Vietnam zeitgeist, and plenty of people heard it as an allegory about American foreign policy. The hard rock genre was still in its infancy, and it presumably hadn't become its own walled-off world with its own radio stations. (The term "album-oriented rock" didn't come into vogue until the mid-'70s.) And probably most importantly, it's a hell of a song.

The Guess Who had been around, in one form or another, since 1958. They'd come from Winnipeg, and they'd been through a whole lot of lineup and name changes before accidentally settling on their final band name in 1965. (They'd been Chad Allen & The Expressions, but their label had tried to build mystique by marketing them as "the Guess Who?," and the name stuck.) They'd had big Canandian hits and minor American hits, and they'd worked for a while as a house band on the CBC TV show Let's Go, which Chad Allen hosted for a while after quitting the band that had previously been named after him. The Guess Who didn't start out as hard rock, and they never really recorded a song harder than "American Woman." They never recorded a better song, either.

"American Woman" has a fun origin story. The group wrote it onstage. Band members have never agreed on where they were, but they were playing somewhere in Southern Ontario, possibly at a Scarborough curling rink. Guitarist Randy Bachman, who would soon quit the band and eventually form Bachman-Turner Overdrive, had broken a string, and he was tuning up onstage after replacing it. He started playing a riff, and people in the crowd started paying attention, so he kept playing it. Eventually, the other band members joined him onstage and started playing along with that riff. Singer Burton Cummings sang the first thing that came into his mind, and that was, "American woman, stay away from me!" After the show, the band found a kid in the crowd who'd been bootlegging the show on a tape recorder, and they got him to give them the tape.

Most of the time, the Guess Who were a pretty standard blues-rock band who knew their way around a hook. But in "American Woman," you can hear all the immediacy and urgency of this band trying to keep a crowd's attention and stumbling into something great. The riff is a total steamrolling monster. The drums are a big, funky tumble, syncopated enough that you could actually dance to them if you were so inclined. Cummings immediately works himself into a froth, sounding both disgusted and intrigued by the idea that this American woman is into him. He's got a great raw-throated howl, and you can practically hear the veins popping off of his forehead, but he has fun, too. The bit where he's yelling, "Bye bye!" over and over is almost deliriously silly.

The members of the Guess Who have never been entirely clear on whether they intended "American Woman" to be a protest song. Cummings once said, "What was on my mind was that girls in the States seemed to get older quicker than our girls and that made them, well, dangerous." And it's funny to think about this ferocious hard rock anthem coming into existence because this Canadian boy freaking out over the intimidating women he was meeting further south. But other members of the band have said that "American Woman" is, in fact, a political song, and the lines about "your war machines" and "your ghetto scenes" bear that out.

In both interpretations, of course, "American Woman" is a song from a Canadian band who are angry at and suspicious of their neighbors to the south. And yet this didn't stop Americans from embracing "American Woman." (Technically, "American Woman" went to #1 as a double-A-sided single, with the giddy half-acoustic stomp "No Sugar Tonight." But it's pretty clear that "No Sugar Tonight" is just a B-side. It's a good one, though; I'd put it at an 8.)

Maybe American listeners liked the perceived anti-war message in "American Woman," or maybe they just heard the word "American" and didn't hear any of the criticisms in the song. Maybe they liked the song so much that they didn't mind. Still, it's pretty amazing that the first Canadian act ever to hit #1 on the Hot 100 did it with an explicitly anti-American song. It's like if Bret Hart had turned heel and nobody had noticed, if he'd only gotten more popular because of it.

GRADE: 9/10

BONUS BEATS: I need to talk about Lordz Of Brooklyn here. Lordz Of Brooklyn were a white rap group in the '90s who rapped about being Italian in the same way that House Of Pain rapped about being Irish. They used gangster-movie accents and wore leather jackets and fedoras and leaned into the gimmick as hard as they could. (They still exist as the Lordz, and now they do a sort of punk/rap hybrid.) Rick Rubin signed Lordz Of Brooklyn to his Def American label, and they put out an album called All In The Family in 1995. The album did not sell, and I bought it from a cutout bin for a couple of bucks soon afterwards. And I loved it.

Lead single "Saturday Night Fever" samples "American Woman," and it is so good. "Connected like Sinatra / The Phantom Of The Opera / The turnstile hopper / Fuck those coppers!" Here's the video: