Breaks With Tradition is a Stereogum column that examines a certain song that’s been frequently sampled and how that song has been used through the years.

When songwriter/composer/pianist Galt MacDermot passed away last week one day shy of his 90th birthday, the people who memorialized him could be paired off into two distinct camps. In The New York Times and most other mainstream news outlets, the headline and first paragraph of his obit focused on the fact that he composed the score for hippies-go-Broadway musical Hair. (This despite the fact that he was 40 at the time and didn't even drink, much less trip; nevertheless his style could adapt.) But if you follow anyone online who even slightly scrapes up against that cratedigger/vintage-schooled hip-hop head demographic -- like hip-hop's own Scorsese-level advocate Questlove -- you saw him eulogized above all else as a producer's favorite, the man who gave us future foundations for legendary tracks by Busta Rhymes ("Space"), J Dilla ("Golden Apples - Part II"), Handsome Boy Modeling School ("Coffee Cold"), MF DOOM ("Princess Gika"), and even Run-DMC when Pete Rock gave them a beat ("Where Do I Go?").

If all those artists embody a certain Golden Era-rooted notion of hip-hop beats being able to come from anywhere, then it makes perfect sense that MacDermot's music was such a widely used source. A pianist with a background studying African music, a proficiency in jazz, and an affinity for funk but no particular allegiance to a single category, MacDermot's music is often best described in terms of what mood it evokes than what genre it belongs to. And few of his creations feel like they really hit that note of scene-over-style than the preposterously/evocatively-titled "Ripped Open by Metal Explosions," a 1970 instrumental that was used by producers from all sorts of locales but somehow still all comes down to a very specific strain of East Coast boom-bap. How this particular track came to embody a certain weather-worn, grimily buzzed/zooted/dusted strain of hip-hop from Newark to Brownsville to Flushing is anybody's guess, but this timeline could help sort it all out.

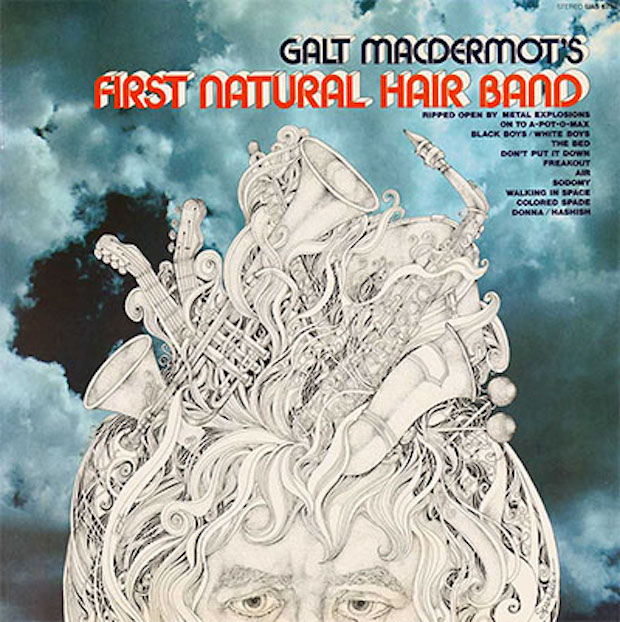

The Original: Galt MacDermot's First Natural Hair Band, "Ripped Open by Metal Explosions" (from First Natural Hair Band, United Artists, 1970) Did not chart.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=PK_awx2Deyg

Before everything else, there's that noise -- a sound onomatopoeia can't really do justice to. It's a boing and a clang and a twang and a bounce all at once, something you can pick apart to its components (oh wait that's a bass note, that's a wah-wah guitar, there seems to be a marimba in there somewhere), yet never really get to the bottom of. The liner notes to First Natural Hair Band denote this instrumental, a rework of the Hair song "Three-Five-Zero-Zero" titled after a paraphrase of its first line, as "a frightening interlude to hallucinations," and that makes sense in context; there's something distinctly altered about the state of this song's affectations even if the muted trumpets and that counterpoint sax moan dredge up half-remembered montages of Lost Weekend drunkenness before they do anything psychotropic. But as a reinterpretation of a moment in the original musical dedicated to recounting the horrors of war, it could also hint at a less recreational altered mind state -- the restless edge of post-traumatic experience.

In any case, it's worth pointing out that the band in question here is the same band that played the Broadway stagings of Hair from the get-go -- and that this band includes a few names worth knowing that sample-searching, jazz-savvy producers knew were worth remembering. Idris Muhammad might be the most obvious -- the drummer whose bandleader efforts laced everything from the Beastie Boys to 2Pac to Fatboy Slim to Jamie xx, and who left an even bigger impression as a sideman on a grip of Blue Note, Prestige, and CTI soul-jazz classics in the '70s (including, yes, the Bob James album that gave us "Nautilus"). Basically if you own more than ten hip-hop records you have something that sampled a song he played on, unless you're some kind of 808s-only purist. Guitarist Charles Brown III had session gigs playing jazz, country, soul, and all points in between; it's a toss-up as to whether the most noteworthy recording he's on is Bonnie Raitt's cover of John Prine's "Angel From Montgomery" or Barry Manilow's "I Write the Songs". Bassist Jimmy Lewis's career stretched improbably and spectacularly from Count Basie's Big Band in the '50s to David Clayton-Thomas in the '70s, with gigs in the '60s playing for both blues guitarist John Hammond and jazz organist Johnny "Hammond" Smith. And trumpet/flugelhorn players Martin Banks and Eddie Williams don't have a ton of credits to their name, but the ones they do are choice: Banks gigged with both blues master Freddie King (Freddie King Is A Blues Master) and Archie Shepp (For Losers) in the late '60s, while Williams appeared on a series of Lou Donaldson albums for Blue Note -- Hot Dog, Everything I Play Is Funky, and Cosmos -- that made up for in sample-friendly funk what they lacked in jazz-purist cred.

Incidentally, there's an alternate version of the song that Eothen "Egon" Alapatt unearthed during his pre-Now Again years working for McDermot's label Kilmarnock where Galt plays piano in place of all those wild horn melodies, and it is a jam and three-quarters.

The First/Breakthrough Sample: Artifacts, "C'mon Wit Da Git Down" (from Between A Rock And A Hard Place, Big Beat Records, 1994). Did not chart; album peaked at #137 on Billboard 200, #17 on Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums

Fuckin' Buckwild, everybody. I know it's a total Old Head Move to yammer about how great DITC were, but just one of their members produced this, O.C.'s "Time's Up," and Organized Konfusion's "Why" all in the same year, and then did a super-underrated Beastie Boys remix on top of all that while he was at it. If you can think of a better cross-section of one producer's ability to make jazz-derived beats sound like Blast of Silence's New York looks, I'd like to hear it, both as a challenge and as an excuse to hear more grimy '90s boom-bap, because why not. Buckwild's beat for "C'mon Wit Da Git Down" isn't quite in the thousand-yard-stare-over-your-shoulder mode of those other beats I've mentioned, but the way he gets laser-focused on that Lewis/Muhammad rhythm section (boosted with more drums from Average White Band's "School Boy Crush" and beatmaker secret weapon Brethren's "Outside Love") is a strong foundation that he uses to drop in the more off-kilter moments from the original -- horn blats and pieces of that twang dropped in for emphasis before reuniting it all in the hook. Thankfully Artifacts absolutely kill it on this one -- DJ Kaos's scratching hits right, and El Da Sensei sounds like a more laidback precursor to El-P's rapping in hit-every-beat Run the Jewels-era mode, which is funny because it's Tame One of the did he just... "word to my grandma's tampons" one-liner who joined the El-P-featuring supergroup The Weathermen. Anyways, hopefully I've just added a few names to your shopping list.

The Early Sample: Public Enemy, "I" (from There's A Poison Goin On, Atomic Pop, 1999). Did not chart.

Often if someone in DITC is the first to flip a beat, they're the best to flip a beat; I doubled-up the First and Breakthrough Sample categories for Buckwild for a reason. But Buckwild's rework of "Metal Explosions" was so thorough that almost nobody else touched it for five years. (One history-clouding exception was Beatnuts-affiliated producer Victor "V.I.C." Padilla's beat for "Burial Ground" by brief RCA signee Bas Blasta -- given the 1994 copyright I've seen attached to the promo-only tape there's a possibility that V.I.C. got there first, especially considering that he actually went so far as to seek out the reclusive MacDermot personally back in '93 and go through his albums at his house. Also, V.I.C. made a couple beats for Artifacts' second album; small world huh?)

Now that I've written over 100 words in an effort to postpone reckoning with post-Shocklee, post-Def Jam Public Enemy, here's just that -- an album ahead of its time in its internet-retail status, behind its time in its steadfast refusal to give quarter to octuple-platinum mainstream rap, and unstuck in time in its tendency to care more about whatever sounds good than whatever sounds current. This is the album that gave us psychedelic wig-out anthem "Do You Wanna Go Our Way???" -- brilliantly sourced from an acid-rock cash-in 101 Strings record, of all things -- so I'm not going to cast too many aspersions on it except for the requisite "you really called one of your tracks 'Swindler's Lust,' huh" side-eye. Especially since the "Tom E. Hawk" that produced to the "wait, who" bafflement of many is just Gary G-Wiz maintaining the connections he first made on Apocalypse 91. "I" was released as the "Go Our Way" b-side when the latter dropped as a single in the UK, which is why it's easy to think of it as psychedelic in itself thanks to the context of its flip-side and its source material. But this is closer, especially lyrically, to the more weary and hard-living side of what "Metal Explosions" evokes, a more simplified chop than what Buckwild pulled off but with the always-overpowering instrument of Chuck D's voice personifying the trapped-in-the-self fatigue of being a transient "Invisible Man times three, Black, down and out." Not all frightening interludes to hallucinations need drugs, or liquor, or even a psychological condition -- they just need open eyes.

The Weirdo Sample: Thirstin Howl III, "Brooklyn Hard Rock" (from Skillionaire, Skillionaire Enterprises, 1999). Did not chart.

Aside from being a showcase for one of the least-precedented, never-imitated voices in underground hip-hop -- anyone else remember hitting this track on Soundbombing II and going wait what? -- Thirstin Howl III's "Brooklyn Hard Rock" is the bilingual-spitting Puerto Rican producer-MC's best-possible introduction to a wild catalogue that also includes tracks about living with his mom, wanting to get with Penelope Pitstop, and wearing hell of Ralph Lauren. It's basically just punchline-metaphor-punchline-punchline-simile delivered at his most manic and elastic-voiced -- "Done played with a full deck, as positive as my drug urine test/My rhymes do to your brain what bullets do to flesh!" -- which makes the brassy lope of the keep-it-simple loop he made from "Metal Explosions" work so well as a comedic underscore, even if he didn't alter it with the same finesse that Buckwild or V.I.C. or G-Wiz did. By '99 it's a known quantity of a sample, but who cares -- what's the point of even leveling beat-biter accusations at someone who uses that beat to brag "even my bible's stolen"?

The Recent Sample: Your Old Droog, "Bad to the Bone" (from Your Old Droog, self-released, 2014)

Right, so it turns out dude wasn't Nas -- so instead we get to be around for another MC who's good enough to be mistaken for him rapping under a pseudonym. Shit, I'll take that, especially since that comparison mostly fit his flow and lyricism more than his raspy voice itself. Makes sense that the two name artists who sampled "Metal Explosions" this decade were Droog and Action Bronson, Bring-New York-Back candidates who got ridden/mocked for sounding like the best MCs of 1994, though I'll take this El RTNC beat over the one Bronsolino rapped over just because it's murkier, more restless, more deftly rearranged (the horns first come in at the perfect moment on the hook), and does a lot with just the piano/bass/guitar; notice how muffled and muted the drums feel and ask yourself how long it actually took you to notice.