As the Knife, siblings Karin and Olof Dreijer made instant goth-electro classics. From Deep Cuts' breakthrough hit "Heartbeats" to singles like "We Share Our Mother's Health" on Silent Shout, their music was bright and sharp, sinister and playful. The Knife made deranged club albums that demanded collective exuberance. Silent Shout won six Swedish Grammys when it was released in 2006 and was critically acclaimed in the United States, becoming a popular go-to at loft parties and in art school dorm rooms, kicking off indie's electronic turn.

[articleembed id="1857786" title="'Silent Shout' Turns 10" image="1857788" excerpt="The Knife's radical ode to the dancefloor still sounds fresh a decade on."]

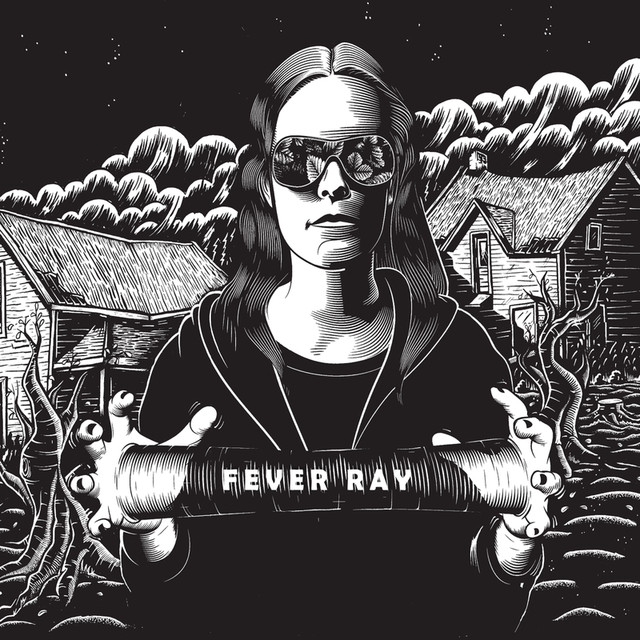

But after seven years of intense collaboration, both siblings felt the need to take some time off. Once the Shout tour wrapped, Olof went to Berlin and Karin to Stockholm, where she took up a much quieter life. The Knife revealed little about their personal lives, but behind the plague doctor mask, the woman who gained worldwide renown for queering cyborg feminism in the club was married to a computer programmer and had just given birth to her second child. Dreijer's world refocused inward: creative impulses sparked during five AM walks with a stroller to the first streetlight or the first tree in the park ("Triangle Walks"), then took form during long trips to her studio south of Stockholm, where Dreijer began writing what would become her self-titled solo album under the moniker Fever Ray, which turns 10 this weekend.

Outside of the club, Dreijer's tempos slowed down. Synth-pop proclivities grew warped and somnambulant amidst a darkness as pervasive and as matter-of-fact as a four PM sunset in December. Any period of forced stasis can be both claustrophobic and generative, depending on how long the cocoon feels like it's going to hold. Critics, mostly men, reviewed Fever Ray as "creepy," and "eerie." To me, its interiority has always sounded powerful, coiled with the deepest yearning. It is a restless album, patient, but only because it has to be. Its desire is agonizing.

"When you have kids you're very isolated," Dreijer told musicOMH. "You are awake at night and you're awake in the day too. It's a very strange, zombie-like time." With the border between sleep and waking life rendered permeable, seepage from the dream world filters through. Here, there are shapeshifters. As with her work in the Knife, Dreijer pitch-shifts her voice, inhabiting different characters, instruments, genders. She is the child and the crone. The call and the response.

On the arresting "Keep The Streets Empty For Me," which holds as the album's tranquil anchor, Dreijer is a soft animal savoring the peace of the pre-dawn world before it is remade and repopulated. (The only track where Dreijer's voice is wholly unprocessed, guest vocals by Cecilia Nordlund provide a doubling that is just as uncanny as the rest of the album.) The first two songs, "When I Grow Up" and "If I Had A Heart" could be written from either her child's perspective or Dreijer's own. Either way, the narrator is someone whose feet never reach the ground, something in the process of becoming.

In vampire movies, women and children are frequent avatars of unrepentant want — they embody a patriarchal fear that those without agency in the waking world are just sharpening their teeth, waiting for their moment. Think Claudia in Interview With The Vampire, Lucy in Bram Stoker's Dracula, Drusilla in Buffy The Vampire Slayer, Akasha in Queen Of The Damned. Restrained, desire only grows. Fever Ray opens with the line, "This will never end 'cause I want more/ More, give me more, give me more." On "When I Grow Up," someone has cucumbers on their eyes, Prufrock-like, "waiting for a moment to arrive." In the video, a rag-clad figure teeters on the edge of a diving board above an increasingly agitated swimming pool, never jumping in. On "Keep The Streets Empty for Me," the narrator sings, "On a bed of spider web/ I think of how to change myself," and closes with the refrain: "We were hungry before we were born." On "Dry And Dusty," lovers are capsules of energy, untouched, ready to explode.

Of course, we now know that this is a precursor to an album whose moodboard includes ball gags, latex, and play parties. Throughout 2017's Plunge rollout, Dreijer spoke openly about her divorce and subsequent embrace of a queer futurity that reconciles parenting with chosen family, and the pleasures of utopian, unapologetic cruising. If the self-titled whispers in passing of "bruises, asses, and hand claps," Plunge marks the moment where the figure on the diving board finally launches into the pool — where dry and dusty becomes wet.

Despite this, Fever Ray isn't without its moments of release. "Seven," a soaring dance single rooted in domesticity and longtime friendship, hits a moment of triumph when the narrator refuses to explain herself to anyone. Elsewhere, Dreijer's songwriting balances out impressionistic dream logic with a plain record of everyday details, which has the wonderful effect of making hooks out of lines like, "We talk about dishwasher tablets," and, "Magpies, I throw sticks at them." Björk once famously described Vespertine — another perfect winter album — as music for the home, a soundtrack for making a sandwich. On Fever Ray, Dreijer shows you the sandwich.

Fever Ray feels sonically kin to Vespertine as well. Both artists used these albums as creative opportunities to break from techno-maximalism and pursue what Björk has called "electronic folk music." While primarily composed in Ableton with software synths and drum machines, Dreijer countered digital ascetism with a fullness created through recorded guitar samples and pitched-down vocals in a nod to chopped and screwed southern hip-hop. Further warmth came from marimba, pan flute, and conga samples, many of which were switched out for recordings of their analogue counterparts by producers Van Rivers and the Subliminal Kid.

At that time, aughts indie was overflowing with white artists influenced by other white artists trying on "tribal" aesthetics like a Coachella headdress (Animal Collective, Tomahawk, Prince Rama), and, at its most dated, Fever Ray falls into this sonic trap. But elsewhere, the percussion haunts the album like an affable poltergeist, giving "Seven" its playfulness and sense of forward momentum, "Triangle Walks" its mysticism, and "Keep the Streets Empty" its muted hopefulness.

[articleembed id="2026772" title="'Merriweather Post Pavilion' Turns 10" image="2026773" excerpt="Animal Collective wanted to do something outsized. They succeeded."]

Although Dreijer began work on the album in 2006, it didn't come out for three years, coinciding with a monumental, optimistic year in indie. Animal Collective, Dirty Projectors, and Grizzly Bear all hit the mainstream with Merriweather Post Pavilion, Bitte Orca, and Veckatimest, respectively. Fresh releases by tUnE-yArDs, Phoenix, and Passion Pit were absolutely ecstatic, and that year's "summer of chillwave" would hone warm electronica to its utmost bike-ride-into-the-sunset potential. It's hard to imagine anyone being weirded out by Fever Ray in today's music climate, which has been heavily shaped by avant-goth and dark electro labels such as Sacred Bones, Tri Angle, Fade To Mind, and Night Slugs. Shortly after, Zola Jesus (who opened for Fever Ray in 2010) would release Conatus, and various rising witch house stars would combine dark pop with rave-ready trap, filling out the shape of goth to come. But against 2009's sun-kissed backdrop, Fever Ray felt singular — critically respected but as solitary as its protagonists.

Maybe the party pop eclipsed it, or maybe albums tend to come to us when we really need them, but Fever Ray didn't really strike me until almost a full year later. When it did, it caught me restless in a seemingly endless New England winter. Long before I knew its specific context, I connected with it deeply as an album for being not-yet-there — one which understood how disjointed things can feel in anticipation of something undefined. In my last year of college, caught up in an unfulfilling relationship and a scene that didn't feel quite right, everything seemed to vibrate on the verge of some shift I couldn't parse or predict, a need I couldn't yet name. Sleepless on a mattress on the floor I made winter playlists for quiet hibernacula and waited for everything to change. Eventually, it did.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=4F-CpE73o2M

https://youtube.com/watch?v=aX07gCjT7dA

https://youtube.com/watch?v=jWFb5z3kUSQ

https://youtube.com/watch?v=EBAzlNJonO8

https://youtube.com/watch?v=X_50c8QZZyQ

https://youtube.com/watch?v=3VJvZ0hXwAk