In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

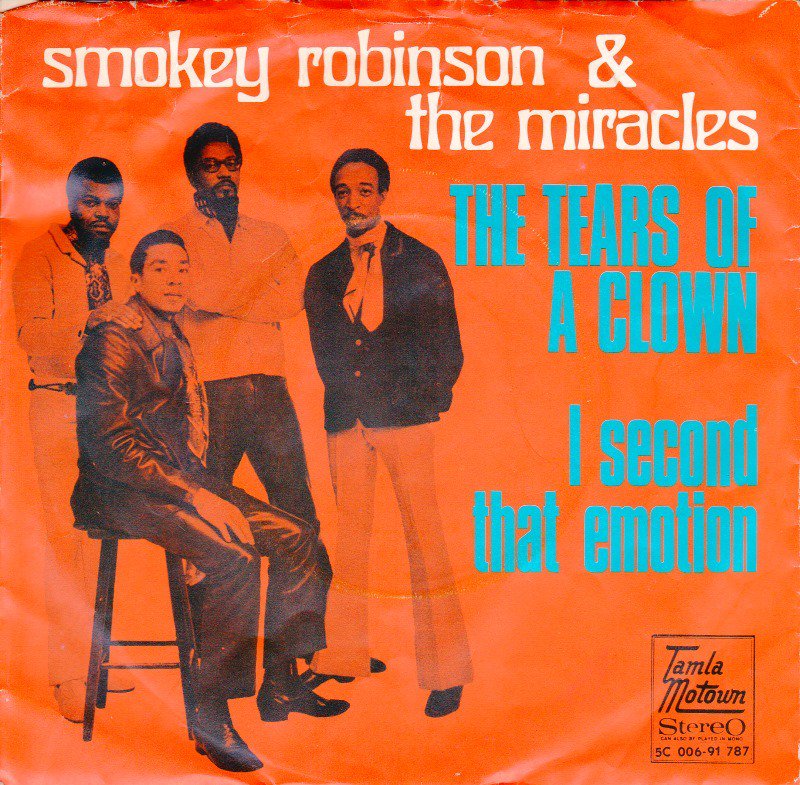

Smokey Robinson And The Miracles - "The Tears Of A Clown"

HIT #1: December 12, 1970

STAYED AT #1: 2 weeks

Smokey Robinson and his Miracles should've hit #1 a full decade before they did. 1960's "Shop Around," an absolutely monstrous banger, was a million-seller, and it was the first major hit for Berry Gordy's Motown company, which was only a year old at that point. But "Shop Around" didn't hit #1. It topped out at #2, blocked by the chintzy colossus that was Lawrence Welk's "Calcutta." ("Shop Around" is an obvious 10.)

Throughout the '60s, the Miracles cranked out hit after hit, landing in the top 10 plenty of times. Many of those hits are absolute classics. ("You've Really Got A Hold On Me," which peaked at #8 in 1962, is a 10. So is "I Second That Emotion," which topped out at #4 in 1967.) During that run, Smokey Robinson and the other Miracles wrote their own songs, and they also wrote for just about everyone else at Motown. In the course of the '60s, Robinson hit #1 twice as a songwriter. He wrote Mary Wells' "My Guy" in 1964, and a year later, he and his fellow Miracle Ronald White wrote the Temptations' "My Girl."

But Robinson and the Miracles didn't get to #1 until Robinson had already quit the group and retired from the stage. And when they got there, they did it with a song that was already years old. "The Tears Of A Clown," the song that finally got them there, was one of the all-time great accidental hits.

Stevie Wonder and his producer Hank Crosby wrote the music for "The Tears Of A Clown" in 1966, and they recorded an instrumental demo for it, but they couldn't come up with any lyrics that suited that instrumental. So they brought it to the Motown Christmas party that year, and they gave it to Smokey Robinson. Robinson thought that the instrumental, with all its ornate woodwind flourishes, sounded like a circus, so he decided to write something circus-themed. He'd been fascinated by the idea of the Italian opera Pagliacci -- the idea of the tragic heartbroken clown who cries as he takes his facepaint off. And so that's what he wrote about.

This wasn't the first time that Robinson wrote about Pagliacci. It wasn't even the first time he used the line "just like Pagliacci did / I try to keep my sadness hid." Robinson had used that same line on "My Smile Is Just A Frown (Turned Upside Down)," a 1964 single that he'd written for the Motown singer Carolyn Crawford. But when someone is writing as many songs as Smokey Robinson was, you can't really blame him for a little self-plagiarizing every once in a while. And maybe you could read more into it. For instance: Here we had a popular black entertainer singing unthreatening songs amid the chaos of '60s America. And you also had a guy trying to maintain some semblance of normalcy while operating a the center of a suddenly-enormous entertainment enterprise. Robinson was never a confessional songwriter, but "The Tears Of A Clown" hints at heavy things beyond its borders.

"The Tears Of A Clown" is also just a formally impeccable pop song, a song that simply and straightforwardly communicates a feeling. Wonder and Crosby's music is a small riot of detail, full of flute tootles and tuba-rattles. The song's bassline doesn't come from a bass; it comes from an oboe. Robinson took that, and he found a way to mirror it. The music is doing what the clown does. It's jumping around, doing dazzling things. And Robinson uses that music to contrast against his voice and against what he's singing. In his pinched and vulnerable tenor, Robinson conveys total loneliness: "Don't let my glad expression / Give you the wrong impression / Really, I'm sad." He doesn't even need to say it. We can hear it in his voice.

"The Tears Of A Clown" is a stunning song, but Robinson and Wonder didn't hear a lot of commercial potential in it. At the time, they didn't release it as a single. Instead, "The Tears Of A Clown" was an album track on the Miracles' 1967 album Make It Happen -- the last song on the album, in fact. It just sat there, in plain sight, for years. In 1969, Robinson decided that he'd spent enough time touring. He was already Motown's vice president, and he and his wife, the former Miracle Claudette Robinson, had two young kids at home. (They named them Berry and Tamla.) So Robinson quit the Miracles.

Then, in 1970, Motown's UK distributor decided that he wanted to release a new Miracles single. There weren't any new Miracles songs, so he asked Karen Spreadbury, the head of a UK Motown fan club, to pick one of the songs from Make It Happen, as a single. The song made it to #1 in the UK, so Motown remixed it and gave it a domestic release, as well. The same thing happened over here. The song sounded nothing like the harder, more psychedelic sounds that Motown was releasing in 1970, and yet it struck a chord anyway. Maybe this is a case of very early-onset '60s nostalgia.

The song turned out to be so big that Robinson agreed to stay with the Miracles for two more years, finally leaving for good in 1970. Robinson didn't stay retired for too long; he released his first solo album a year after he left the group. Robinson went on to have a great solo career, changing his sound with the times, pioneering the quiet storm subgenre, and landing a bunch of other hits. But he never got back to #1. In a weird twist, the other Miracles did eventually score another #1 without Smokey Robinson: the 1975 disco song "Love Machine." But that's a story for another day.

GRADE: 9/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's the English Beat's gorgeously lively 1979 2-Tone ska cover of "The Tears Of A Clown," which peaked at #6 in the UK:

BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's the great UK new romantics ABC's video for "When Smokey Sings," an ode to Smokey Robinson that interpolates the "Tears Of A Clown" bassline:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=eXK71NEFkyI

("When Smokey Sings" peaked at #5. It's an 8.)