In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

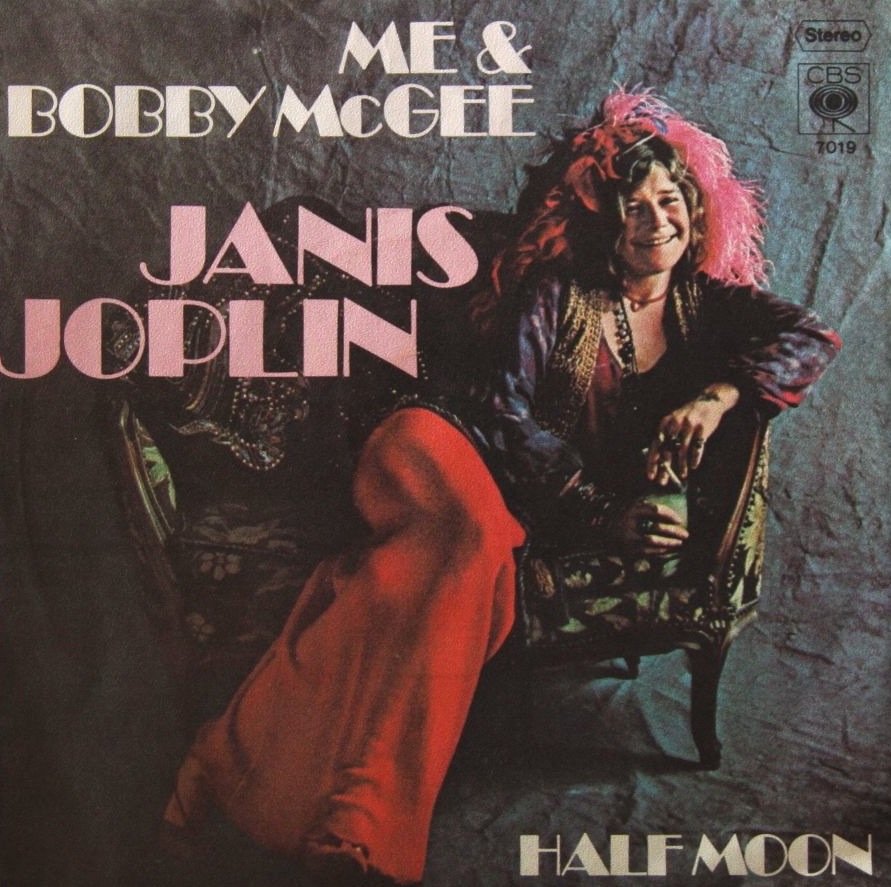

Janis Joplin - "Me And Bobby McGee"

HIT #1: March 20, 1971

STAYED AT #1: 2 weeks

Kris Kristofferson didn't write "Me And Bobby McGee" with Janis Joplin in mind. Kristofferson knew Joplin; they'd actually had a brief fling before Joplin died of a heroin overdose. But he didn't even know she'd recorded the song. The way Kristofferson tells the story, Joplin's producer invited him over to his office one day, shortly after Joplin had died, and played Joplin's version of the song for him. She'd finished recording the song three days before she'd died. Kristofferson spent the rest of the day walking around Los Angeles, crying. He probably wasn't alone. A lot of people probably cried when they heard Joplin singing "Me And Bobby McGee."

Janis Joplin was a terribly romantic figure, and her life story reads like a myth. This quiet girl had grown up in Port Arthur, Texas, bullied and stultified by the yokels around her. But she'd discovered old blues records, Bessie Smith records in particular, and through them, she'd found her superpower. Joplin started singing -- first at local coffeehouses, and then at coffeehouses in Austin, where she was briefly a college student.

Joplin found her way to San Francisco and got herself hooked on heroin. She came home, got clean, then returned to San Francisco and got hooked again. She became a rock star, first singing for Big Brother & The Holding Company and then going solo and leading a series of her own bands. Her voice -- ragged, ferocious, force-of-nature powerful -- imprinted itself on a whole generation of kids. She travelled the planet, slept with men and women, and tried every drug she could find -- though she also went through periods where she tried to get clean. And then she died alone in a Hollywood hotel room after shooting up. Joplin departed in October of 1970, 16 days after Jimi Hendrix. Like him, she was 27 when she went.

To date, there have been six musicians who went to #1 after dying. Joplin was the second. She was the only woman, and she was the only one who died of something that could be described as a long-festering disease. (The others were killed by murders or plane crashes.) The first posthumous #1 was Otis Redding's "(Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay," another virtuosic and bittersweet life-on-the-road song that ends in California. Otis Redding's death had to come as a terrible shock. Maybe Joplin's was, too. But I think a lot of people probably saw it coming, or at least worried that it might happen.

Joplin was never much of a singles artist. She'd had one real hit -- Big Brother & The Holding Company's take on Erman Franklin's "Piece Of My Heart," which peaked at #12 in 1968. Mostly, she was famous for being a motherfucker of a live performer, and for the way her records failed to capture the intensity of those shows. And her "Me And Bobby McGee" isn't really a pop song. It's loose and shaggy and wide-open. And yet, by design or by accident, her version of the song captured the romanticism of the life she lived, as well as the squalor that came with that life. It's impossible to separate her version of the song from her death. In a way, it's almost like she wrote her own epitaph.

Kris Kristofferson was a romantic figure, too. (Come to think of it, he still is.) Kristofferson came from Texas, flew helicopters in the Army, and then turned down an offer to teach English at West Point, deciding instead to try his hand at writing country songs and, in the process, estranging himself from his family. Kristofferson struggled as a songwriter for a while, but he eventually started convincing big country singers to record his songs. (There's a legend about how Kristofferson wasn't making anything happen until 1969, when he landed a helicopter on Johnny Cash's front lawn, and Cash, impressed, recorded Kristofferson's utterly perfect hangover lament "Sunday Mornin' Comin' Down.")

Kristofferson was working as a helicopter pilot in Louisiana when he wrote "Me And Bobby McGee." Fred Foster, Kristofferson's boss at Monument Records, had called Kristofferson before he left for work one day, telling him he wanted him to write a song called "Me And Bobby McKee." Bobby McKee was a secretary who worked in the same building as Foster. Foster had a crush on her, so he gave Kristofferson the assignment, and Kristofferson misheard her name over the phone. (Foster got a co-writing credit, but Kristofferson was the one who wrote the song.)

Kristofferson didn't like to write on assignment, but the idea kept percolating in his head. Finally, partly inspired by the Fellini movie La Strada, Kristofferson came up with a story-song about a couple who hitchhike across the country, losing themselves in the road, before finally parting, learning both the good and the bad sides of freedom.

Roger Miller recorded the first version of "Me And Bobby McKee" in 1969. In Miller's hands, it's a straight-up country song, a charming dirtbag travelogue a lot like Miller's 1964 crossover hit "King Of The Road." ("King Of The Road" peaked at #4. It's a 9.) Miller's version of "Me And Bobby McGee" was a hit, peaking at #12 on the country charts. Plenty of other people recorded their own versions of "Me And Bobby McGee" before Joplin got ahold of it: Gordon Lightfoot, Kenny Rogers & The First Edition, Kristofferson himself. Most of those earlier versions of the song are sedate and contemplative country or folk or country/folk affairs. Joplin did something else with it.

Joplin's "Me And Bobby McGee" starts out as an acoustic folk song, too, but it builds and expands, getting wilder and wilder. And her voice does the same thing. The other singers had used their voices to showcase Kristofferson's precise, evocative words: "Windshield wipers slapping time, I was holding Bobby's hand in mine / We sang every song that driver knew." But Joplin turns those words into sounds. She finds the song's exultant excitement, the feeling of seeing an open road in front of you and knowing that there's nowhere you have to be. But she also finds the raw vulnerability, the sense that you're completely alone in the world and that even a great love affair will end quietly and finally in the middle of the night, when someone slips away near Salinas.

Joplin doesn't sing "Me And Bobby McGee" as a country song, but she doesn't really sing it as blues or psychedelic rock, either. There's not a whole lot of technique in the way Joplin sings it. Instead, she just lets it rip, her phrasing immediate and instinctive. Kristofferson migt not have written the song for her, but she took the song in, internalized it, and turned it into a song about herself. In Joplin's song, Bobby McGee is a man, though that doesn't much matter. And while Joplin might've never hitchhiked across the country with anyone named Bobby McGee, she still took the specific details of the song, and she made them universal. She did what great interpreters do. In the end, "Me And Bobby McGee" really is a song about Janis Joplin, because that's what Janis Joplin made it.

As "Me And Bobby McGee" is winding down, Joplin finally hits the moment where the song turns definitively sad: "I'd trade all my tomorrows for just one yesterday, to be holding Bobby's body next to mine." She wouldn't have many tomorrow's left. Joplin finished recording "Me And Bobby McGee" on October 1, 1970. Three days later, she was dead.

GRADE: 10/10

BONUS BEATS: There are about a million different versions of "Me And Bobby McGee," and we could be here all day if I keep posting them. So we're just going to go with this video of Kristofferson's buddy Waylon Jennings doing his tough and stoic 1973 take on the song:

BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's Kristofferson's most badass moment in 1998's Blade, one of the greatest movies of all time:

BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Oh what the hell, we'll do another "Me And Bobby McGee" cover. Here's Jennifer Love Hewitt's deeply random and almost insanely brave 2002 voice-and-bongos rendition: