In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

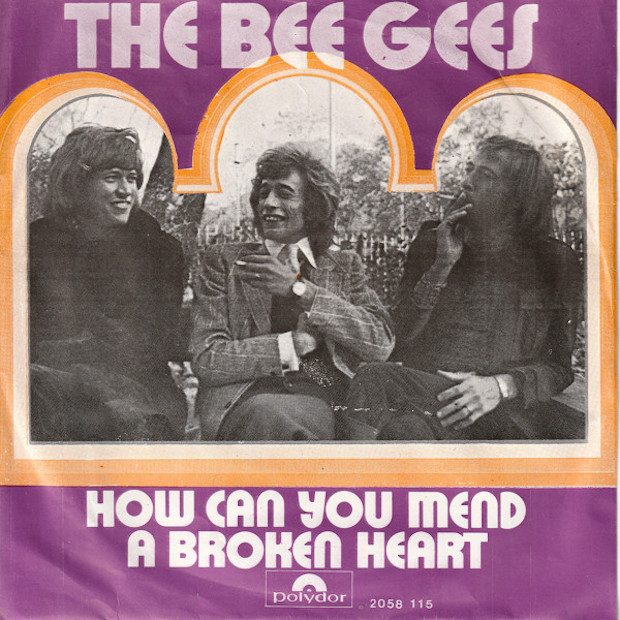

The Bee Gees - "How Can You Mend A Broken Heart"

HIT #1: August 7, 1971

STAYED AT #1: 4 weeks

The Bee Gees were the dominant chart-pop act of the '70s, the closest thing to the Beatles that the decade had. No single act is ever going to tower over an entire decade the way the Beatles towered over the '60s, but the Bee Gees' commercial success in the '70s is still a baffling thing to consider: Nine #1 singles, and a grand total of 27 weeks in the top spot, as well as three #1 singles from youngest Brother Gibb Andy and a handful of huge hits that Barry Gibb wrote for other artists. Of course, most of the Bee Gees' hits came toward the end of the decade, when the group embraced disco and Barry Gibb's falsetto floated atop an entire cultural wave. But the trio already had a couple of complete career arcs before they arrived at that sound. They even had at least one before landing upon "How Can You Mend A Broken Heart," their first American #1.

The Bee Gees -- oldest Gibb brother Barry and younger twins Maurice and Robin -- started playing music together in 1955, when they formed a skiffle group called the Rattlesnakes, and then another one called Wee Johnny Hayes And The Blue Cats. (Imagine if they'd kept that name.) This was on England's Isle Of Man. But in 1958, the Gibb family moved to Australia, and that's where the three brothers really figured out how to become a band. They started out performing in between races at a Brisbane speedway, collecting the money that people in the audience would throw at them. Before long, they were performing on Aussie TV and putting out singles on local labels. (Even then, they wrote all their own songs.) But success took a while, so they returned to England in 1967.

Back in their homeland, the Bee Gees were an instant sensation. On singles like "Massachusetts," a UK #1 that also peaked at #11 in the US, they sang in the kind of close harmony that the Beatles weren't really using anymore, and they did it over lush, layered string arrangements. As time went on, they built that sound up more and more. Robin Gibb sang lead then, and they steered into his weirdly intense nasal quaver of a voice, building up gooey middle-of-the-road strings around him. But they weren't getting along, and Robin left the band in 1969, taking a stab at a solo career while the other two kept going without him. So that's one arc.

A year later, though, Robin called Barry and suggested that they all get back together. Immediately, Robin and Barry sat down and wrote a couple of songs together. (Maurice contributed, too, though he didn't get a songwriting credit until years later.) The first of those songs was the big comeback single "Lonely Days," a florid and string-drenched ballad that peaked at #3 in 1970. (It's a 5.) And that same day, at least according to the brothers themselves, they also wrote "How Can You Mend A Broken Heart."

When they first wrote "How Can You Mend A Broken Heart," the Brothers Gibb offered it to middle-of-the-road crooner Andy Williams. He turned it down, though he did later record his own version. It's easy to hear why the Brothers Gibb might've thought that Williams would've been the man for the song; it's a big and messy glob of honeyed melodrama. Instead, co-producing the song with Robert Stigwood, the Bee Gees shot for soulful, buttery folk-rock, and they came away with something deeply unpleasant.

"How Can You Mend A Broken Heart" has decent melodic bones, and other singers would do great things with it. Maybe the Bee Gees could've done something great with it, too, if they'd done more to build on the edge of hysteria in Robin Gibb's voice. Instead, they smother it in strings and harps and church bells. The song's acoustic-guitar rhythm is a leaden trudge, and so the strings whirl and twirl upward, knocking everything else out of the way in their pursuit of pure grandeur. By the end if it, poor Robin almost sounds like he's yelling just to be heard over them.

Working on this column, even with the songs I don't like, I can usually get some inkling of why they hit a collective nerve when they did. With this one, I'm just baffled. The ripe, humid production was certainly on trend in 1971; most of the songs that hit #1 in that era sound something like this. But the Gibbs' voices clang against that sound in ways that could charitably be described as awkward. They'd find their groove eventually, but they sure as hell did not have it here.

GRADE: 3/10

BONUS BEATS: Al Green, who will appear in this column soon enough, covered "How Can You Mend A Broken Heart" on his 1972 album Let's Stay Together, and he spun it into absolute gold, turning it into a tenderly wrecked six-minute soul odyssey. Here's Green's version:

Green's version of the song is the one that has culturally stuck around, appearing in movies and such. Here, for example, is the bit from 1999's Notting Hill where Hugh Grant wanders around London all sad after seeing Julia Roberts with Alec Baldwin:

And here's the scene from 2010's extremely strange Biblical post-Western samurai bugout The Book Of Eli where Denzel Washington catches a moment of post-apocalyptic relaxation:

THE NUMBER TWOS: Jean Knight's eternally badass soul strut "Mr. Big Stuff" peaked at #2 behind "How Can You Mend A Broken Heart." It's a 9.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=zkClyHdKTzE

John Denver's folksy, bucolic ramble "Take Me Home, Country Roads" also peaked at #2 behind "How Can You Mend A Broken Heart." It's an 8, at least in part because I really love that one scene from Logan Lucky.

THE 10S: Marvin Gaye's lush, bittersweet hymn "Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)" peaked at #4 behind "How Can You Mend A Broken Heart." It's a 10.