In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

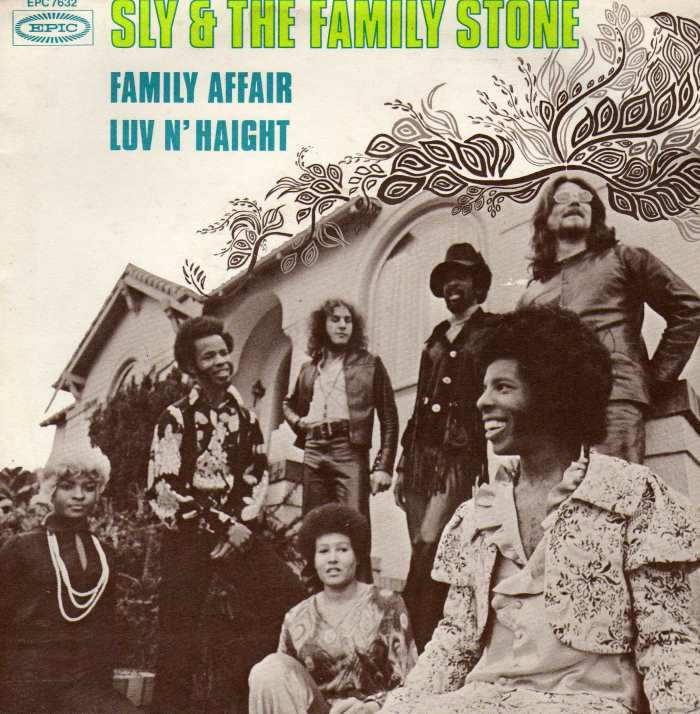

Sly & The Family Stone - "Family Affair"

HIT #1: December 4, 1971

STAYED AT #1: 3 weeks

Decades don't exist. They're a construct, a handy thing that we use to impose historical narratives on the boundless chaos of everyday life. They help us tell stories, and they're convenient for that. But they paint a false picture. Everyone in the '80s didn't wear day-glo Members Only jackets and feathered hair. Everyone in the '90s didn't wear flannel and Chucks. In 2001, a whole lot more people were excited about Ja Rule and Ashanti than about the Strokes.

And yet, sometimes, there's something to those narratives. Consider: the death of the '60s, a story that we've heard again and again and again. Did the entire Baby Boom generation wake up one morning in the early '70s, realize that all their idealistic dreams had withered away, and start hoovering up vast piles of coke? No. Obviously. And yet you can see a certain torpor in the art and the culture that the moment left behind: Fear & Loathing In Las Vegas, A Clockwork Orange, There's A Riot Goin' On.

It makes sense. In just a few years, a whole massive generation had seen itself changing the world. There had been protests and festivals and drug orgies and sometimes all three at once. But there had also been assassinations and beatings and massacres. The assholes were still in charge of the country. The war was still happening. And all those drugs, it turned out, weren't necessarily so magical.

The story of Sly & The Family Stone is not the story of the '60s, and yet all those events line up so neatly. Once upon a time, this band was a great utopian experiment, a pan-racial and pan-gender fusion of starry-eyed psychedelia and hard-stepping soul that left nobody out. But it didn't last. Political turmoil touched the band; there were rumors that the Black Panthers were threatening Sly Stone, demanding that he remove white people from his band and from his life. Stone, meanwhile, was getting all strung out on all sorts of shit. He was hanging out with gangsters and mafia. He was skipping shows and feuding with his bandmates.

After releasing the 1969 landmark Stand!, Sly & The Family Stone went for more than two years without releasing anything other than the one-off #1 single "Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)." That doesn't seem like much today, but this was the era when bands were expected to crank out multiple albums per year. The Family Stone didn't do that. They fractured and disappeared, forcing their label to put out a greatest-hits album just so that they'd have something on the market. And when they did return, they came back with a symphony of night sweat and bad faith, a disturbed and inarticulate lurch of an album that divided their audience. But they still went to #1. Maybe that's a testament to how good they were, or maybe it's a testament to how many people were feeling the same way that Sly Stone was.

"Family Affair," the single from There's A Riot Goin' On and the last Sly & The Family Stone song to hit #1, wasn't really a Sly & The Family Stone song. Nothing on the album was. Sly Stone, paranoid and self-isolated, basically made the album himself, without the input of his bandmates. "Family Affair" has vocals from Sly's sister Rose, and it's got keyboards from his friend Billy Preston. Sly played everything else himself: vocals, guitar, bass. Drummer Greg Errico had left the band, and so Stone replaced him by programming a rhythm box, which means "Family Affair" is the first-ever #1 single with a drum-machine beat. It's a sharp sidle of a drum track, and yet its mechanical stiffness works in sharp contrast to the woozy looseness of the band's earlier material.

The whole album -- titled as a literal response to Marvin Gaye's What's Going On -- is like that. There are moments of giddy, explosive melody, but they're buried in murk and growl. There's tape hiss all over the album, since there was no clean way of putting together an album where one guy plays almost everything. "Thank You For Talkin' To Me Africa," the album's final track, remakes "Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)" as a grim seven-minute death-march. This was heavy music, and it reflects the state of Sly's mind at the time. Consider, if you will, this Rolling Stone interview. When asked which of the instruments he played on the album, Stone responds with this: "I’ve forgotten, man. Whatever was left. Clean your nose, Rich. Jesus. All this stuff and shit. You’ll never know about the sessions. You gotta be there. If you wanna ask a question, talk into my mic, man."

That's about the level of coherence that Stone brings to "Family Affair." It's not a clearheaded protest song. It's not a clearheaded anything. Some people hear "Family Affair" as a song about the Black Panthers, or about the turbulence within the group. In that Rolling Stone interview, Sly remained evasive: "Song’s about a family affair, whether it’s a result of genetic processes or a situation in the environment."

And the song itself doesn't offer any clues. Sly's voice is a craggy mutter, ravaged and tired even when he's yelping. His words are half-formed thoughts: "You can't cry cuz you'll look broke down / But you're crying anyway cuz you're all broke down." There's no central idea to the song -- at least, not one that you could put into so many words. Instead, there's a sweaty, disconsolate vibe.

But "Family Affair" isn't a Jandek song. For all its dope-sick hopelessness, it's still a frisky, playful jam. It's catchy. You could, if you were so inclined, dance to it. Sly's own rubbery bassline anticipated disco, and Preston's electric-piano flourishes add little accents of gospel ecstasy. Rose Stone only sings four words on the song, and yet her voice, clear and strong, still anchors the song and gives her brother something to orbit around. The song didn't get to #1 just because it expressed some frustrated generational lost-paradise feeling. It got to #1 because people liked hearing it.

In the years after Riot, Sly & The Family Stone would release a couple more albums, to diminishing returns. After the band dissolved, Sly released a couple of his own solo albums, and then he faded out into decades-long seclusion, punctuated by occasional drug arrests or performances like the brief and weird comeback at the 2006 Grammys. In 2011, the New York Post reported that Stone was homeless, living in a camper van parked in LA's Crenshaw neighborhood. He's still out there, somewhere -- a living ghost, haunting other people's long-lost hopes.

GRADE: 9/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's the version of "Family Affair" that Shabba Ranks and Patra contributed to the soundtrack of the 1993 movie Addams Family Values:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=uByYfM2AcfI

BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's Iggy Pop's tensely ruminative 1999 cover of "Family Affair."

BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's Ghostface Killah's "Dogs Of War," the 2006 Pete Rock-produced posse cut with verses from Trife Da God, Raekwon, Cappadonna, and Ghost's son Sun God:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=82QY6C6cesc

(I once went to a New York show where Ghostface introduced Sun God like this: "He came out of my dick!")