In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

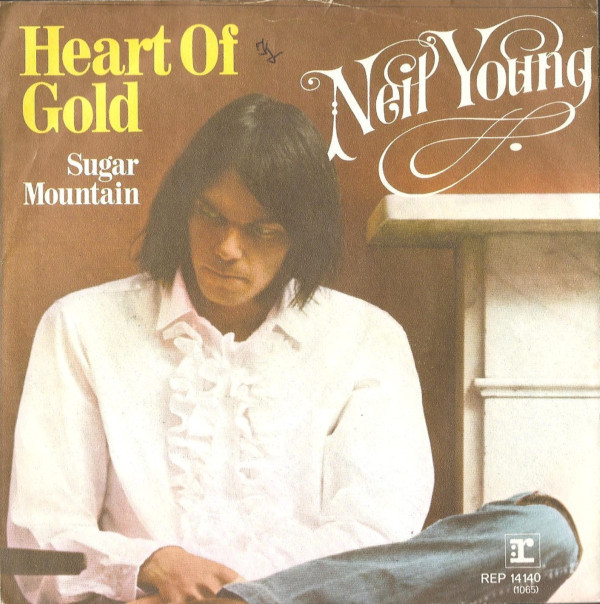

Neil Young - "Heart Of Gold"

HIT #1: March 18, 1972

STAYED AT #1: 1 week

Someday in the long-distant future, when this column is all caught up with the Hot 100, I might have to write a similar column about the list of the best-selling albums of every year. It is a fascinating fucking list. There are so many Broadway cast recordings on there. The Monkees. Iron Butterfly. War. Asia. Billy Ray Cyrus. A Josh Groban Christmas album. And one of the most fascinating albums on the list is a record that Neil Young basically made on the spur of the moment.

In early 1971, Neil Young was in the midst of a now-legendary solo-acoustic tour, and he came to Nashville to play his new heroin-blues song "The Needle And The Damage Done" on The Johnny Cash Show. While he was there, the producer Elliot Mazer, who'd just opened the Quadrafonic Sound Studio, invited Young to come through and tape a session. Young loved the idea that Area Code 615, a group of Nashville country studio musicians who'd backed up Young's idol Bob Dylan on Blonde On Blonde and Nashville Skyline, had recorded at the studio.

Young asked Mazer if he could round up the members of Area Code 615, but this was a weekend, and Nashville session guys are strictly nine-to-fivers, so Mazer was only able to get one of them, drummer Kenny Buttrey. But Mazer did manage to cobble together a band of seasoned country studio guys, some of whom had never even heard of Neil Young. Together, in a couple of days, Young and these Nashville guys ended up banging out the bones of what would become Young's album Harvest. That LP would become the album-sales champ of 1972, and it would also give Young the only #1 single of his career.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=sH_QroMnBwY

Young wasn't exactly a star when he made Harvest, but he'd been around. After surviving polio during the last moments when anyone was getting polio, Young had spent his childhood moving around Canada. He started playing in rock bands as a teenager in Winnipeg, and his group the Squires made a local hit in 1963 with a pretty badass instrumental called "The Sultan." Not long after, he also started writing folk songs; the Guess Who had a minor Canadian hit with a cover of his song "Flying On The Ground Is Wrong."

When Young moved to Toronto, he joined the Mynah Birds, a band led by Rick James, which is fun to think about. That band signed to Motown, which is even more fun to think about. They recorded a never-released Motown single, but the deal fell apart when James was arrested for being AWOL from the US Navy. So Young and his Mynah Birds bandmate Bruce Palmer sold the Mynah Birds' equipment and used that money to buy a Pontiac hearse. Then they drove that hearse to Los Angeles and started the Buffalo Springfield.

The Buffalo Springfield only lasted a couple of years, but they still managed to become one of the defining psychedelic rock bands of their era. (The Buffalo Springfield's sole top-10 hit, 1967's "For What It's Worth," peaked at #7. It's a 10.) When that band broke up, Young released a self-titled singer-songwritery solo debut, formed Crazy Horse, and dropped the absurdly important 1969 fuzz-rock masterpiece Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere. He briefly joined his old Buffalo Springfield bandmate Stephen Stills in Crosby, Still, Nash & Young, played Woodstock with them, and wrote the Kent State protest anthem "Ohio" for the group. (It peaked at #14.) After Young split from that group, he released the shattering 1970 folk-rock elegy After The Gold Rush. Young packed so much into such a short amount of time that it boggles the mind. And none of it captured the national imagination the way Harvest did.

Part of the magic of Harvest is, I think, how spindly and loose it is. Young and the Nashville guys recorded a bunch of tracks before they even properly introduced themselves to each other. The Nashville musicians were total alchemists, capable of summoning pathos on demand. That was, after all, their entire job. And while Young always wanted to be Bob Dylan rather than Hank Williams, he had plenty of the latter in his scraggly tenor whine. They made sense together, especially recording on the fly, with no forethought.

"Heart Of Gold" is not a lyrically complicated song. Young, we learn, is looking for a girl. He's been all around the world -- to Hollywood, to Redwood -- but he can't find the right person. Given the context of the time, we can probably infer that this is a song about getting tired of groupies and wanting a stable relationship. This is total rock-cliché stuff. But Young sings about that search in vast, mythic terms: "I've been a miner for a heart of gold." And he sounds bedraggled and beaten-down, crushed by the weight of his own expectations and the feeling that he's running out of time. "And I'm gettin' old," he laments. Neil Young was 26 when he wrote "Heart Of Gold." But then, Neil Young has never sounded remotely young, and that's one of the great things about him.

James Taylor and Linda Ronstadt, both in town to play that same Johnny Cash Show episode, sing backup on "Heart Of Gold." Their high and clear vocals come in at the end, offsetting the craggy dust in Young's voice and pushing the song to another level. They're lovely, but neither Taylor nor Ronstadt could've ever sung lead on a song like this and make it hit as hard as Young did. He sold a song like this simply by sounding utterly devastated.

"Heart Of Gold" plays as a graceful swoon, a brave plea from a wounded soul. The song connects dots between folk and country and rock, but it doesn't feel too thought-out or triangulated. It's soft and unforced, like Young internalized all these sounds and made them a part of his language. Years later, Bob Dylan said that, even though he liked Young, he'd get pissed off every time he heard "Heart Of Gold" on the radio: "I'd say, 'That's me. If it sounds like me, it should as well be me.'" But Blood On The Tracks was still three years away. In the early '70s, Dylan wasn't recording anything anywhere near that powerful.

Like so many other great artists, Neil Young didn't like the way vast commercial success affected his life. So he went left, again and again. He went so left that, a decade after Harvest, Geffen Records, Young's label, sued him for making music that was "unrepresentative" and anti-commercial. In the liner notes of Decade, his 1977 compilation, Young wrote this about "Heart Of Gold": "This song put me in the middle of the road. Traveling there soon became a bore so I headed for the ditch. A rougher ride but I saw more interesting people there." And that's what he did. In the years since, he's never come anywhere near the top 10.

GRADE: 9/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's Boney M's berserk 1978 disco-funk cover of "Heart Of Gold":

BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's the intense, proggy version of "Heart Of Gold" that Tori Amos included on Strange Little Girls, the 2001 concept album where she covered a bunch of ultra-masculine songs:

BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's Johnny Cash, the man whose TV show accidentally made Harvest possible, covering "Heart Of Gold" in a Rick Rubin-produced version that was included on the posthumous 2003 compilation Unearthed:

(Cash's highest-charting song is a live 1969 version of "A Boy Named Sue," recorded at San Quentin State Prison. It's an 8.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's Anderson .Paak's covering "Heart Of Gold," with verses from Nocando and milo and a quick interpolation of Trinidad James' "All Gold Everything," on the pre-fame 2013 album Cover Art:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=jYRDVH85WR0