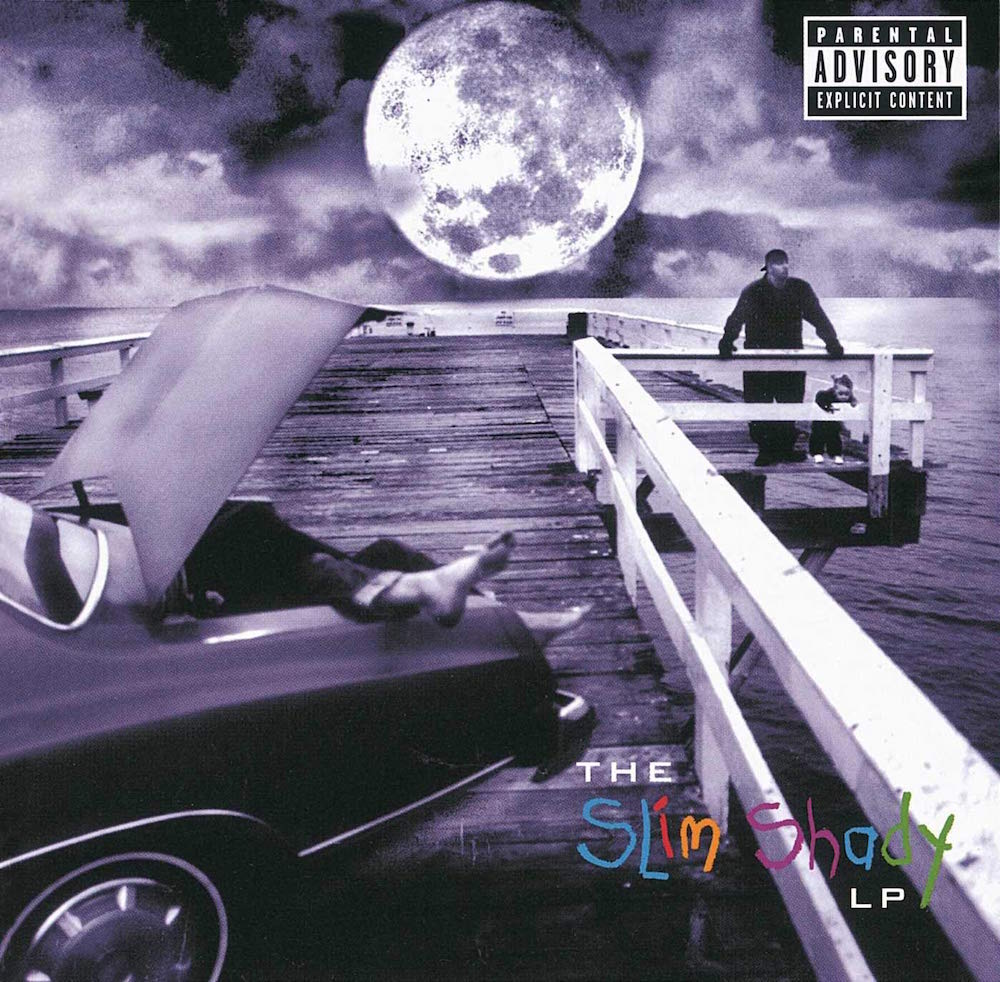

"How the fuck can I be white? I don't even exist." I could write a term paper about a line like that. In fact, I did. I wrote two or three of them. That's what you did when you were a college English major when The Slim Shady Album came out. Those term papers were, in retrospect, largely bullshit. Most of the papers I wrote in college were bullshit. Being an English major mostly involves learning how to bullshit, an ability that has served me well in my chosen profession. And The Slim Shady LP was, as I was just learning to say, a rich text.

Eminem was obviously not the first white rapper. The Beastie Boys' License To Ill was the first rap album ever to get to #1. Vanilla Ice's "Ice Ice Baby" was the first rap single ever to get to #1. But before The Slim Shady LP, white rap successes were mostly short-lived novelties. (That extends to License To Ill. When the Beasties became career stars, they did so by veering away from the rap mainstream, cultivating their own record-nerd pocket universe.) When rap reached maturity as a commercially dominant force in the late '90s, white rappers were not a part of the mainstream conversation anymore. Then Eminem came along, flaunting his whiteness and his fakeness and his fucked-up sense of humor and his near-peerless technical dexterity, and he instantly became a star. And he became a star by undermining what rap was supposed to do.

Late-'90s pop-rap was flashy, aspirational music. It acknowledged darkness, but the darkness was something to be overcome. Jay-Z would rap about his drug-dealing past in mythic terms, but it was part of his grand and escapist cinematic tableau. DMX would rap about poverty and struggle and depression, but he used them as adrenal fuel, and as signifiers of how real his own background was. Eminem, on the other hand, challenged the entire idea of authenticity. He did not tell true stories. He told stories about tortures, decapitations, and Hieronymus Bosch hallucinations. He exaggerated rap's violent tendencies, stretching them out to such funhouse-mirror extremes that they revealed the absurdity of the entire enterprise.

That was the point of those papers I was writing, anyway. To me, Slim Shady was a grand and performative artifice, a rap version of what David Bowie had done with his Ziggy Stardust alter-ego. This take has not aged well. A lot of things about The Slim Shady LP have not aged well. When people like Billboard editor Timothy White denounced Eminem at the time, it seemed like moralist hilarity, a holdover from the Tipper Gore PMRC hearings from 14 years earlier. In retrospect, The Slim Shady LP, like pretty much every Eminem album that would follow, is an ugly, queasy, deeply fucked piece of work, a pent-up bugout from a victimized kid who couldn't get his mind around the idea that he was victimizing other people.

And Eminem really was a victimized kid. Marshall Mathers grew up broke and bullied in working-class Detroit, a tough place for a corny-looking white boy, scrawny and always ornery, to be. He worked dead-end jobs, and couldn't even hold onto them. His race -- something that would later help him become the most popular rapper in history -- started out as an obstacle, a reason for audiences to ignore him. When Infinite, his no-label 1996 debut album, died on arrival, he went into profound depression and even attempted suicide. And then he came up with the Slim Shady character, a cartoonishly deranged alias that he used to vent about everything and everyone that ever pissed him off. He released his Slim Shady EP in 1997 and got it into the hands of Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine, and it was off to the races.

By the late '90s, Dre himself was struggling. He'd been the first out the door of the crumbling Death Row empire that he'd co-founded, but when he tried to reinvent himself on the 1996 compilation Dr. Dre Presents... The Aftermath, he'd met general indifference. Still, Dre's imprimatur was unbelievably important to Eminem. If some major had snapped Eminem up and thrown him out into the world without context, he would've come off as an instant novelty. Dre's cosign was a reason to take Eminem seriously. It made the entire idea of a white rapper seem exotic, and it turned Em's whole narrative into a struggle-to-redemption myth.

Musically, Dr. Dre is not a huge presence on The Slim Shady LP. Dre produces one track -- the breakout single "My Name Is," quite possibly the worst song on the album -- and co-produces two more. Other than the odd cameo, he only really raps on "Guilty Conscience," a song that once seemed like an endlessly clever writing exercise and now comes off as something much darker. Most of the production comes from Eminem and longtime collaborators the Bass Brothers, and a lot of it is just repackaged tracks from Slim Shady EP. Oddly, that's a good thing. The Slim Shady LP doesn't sound like a late-'90s major-label rap album. It has all the immediacy and bounce of Eminem's Detroit-underground roots, and its low-budget fury helped it stand out even further.

The rapping on The Slim Shady LP is just staggering. Eminem has become even more technically precise in the 20 years since the album came out, but he's never locked onto beats the way he did on that album, and he's never shown the same dizzy love of language. There are phrases on The Slim Shady LP that will still get stuck in my head for hours at a time: "I got bitches on my dick out in East Detroit because they think that I'm a motherfucking Beastie Boy," "I get a clean shave, bathe, go to a rave, die from an overdose, and dig myself up out of my grave," "My mind won't work if my spine don't jerk." These days, when Em is torturing his metaphors and cramming as many syllables as possible into every bar, I wish he could recover some of that verve. It's the difference between "good rapping" and good rapping.

He was funny, too. That mattered. It felt weirdly liberating to hear someone spend his entire album bragging about just how pathetic and fucked-up he was, making fun of himself. Em wouldn't flex. Instead, he'd rap about hanging himself by his dick, or getting shitty reviews in The Source. Sometimes, he'd be genuinely furious about his own struggles: "Minimum wage got my adrenaline caged, full of venom and rage." Just as often, though, he'd been mining his own neuroses for laughs: "I get up onstage in front of a sellout crowd / And yell out loud, 'All y’all get the hell out now' / Fuck rap, I’m giving it up, y'all, I’m sorry / But Eminem, this is your record release party." He had the comic timing to sell jokes like that. And when he'd rap about, say, how he really murdered Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman -- something he did more than once on The Slim Shady LP -- it didn't sound too fucked-up, since he'd just spent so much time making fun of himself.

The Slim Shady LP was also an album with a particular point of view. Eminem didn't try to rap like anyone else. If anything, he exaggerated the nasal whiteness of his delivery. And his Michigan accent also helped place him in a particular time and place. Em's whole frame of reference was relatable Midwestern no-hoper shit: Builders Square mall, raves, soap operas, washing dishes. At one point, he went after the future Def Jux rapper and Shia LaBoeuf buddy Cage, his peer in white underground shock-rap, a name that would've been totally foreign to 99% of the 5 million kids who bought The Slim Shady LP. He offered multiple shoutouts to Outsidaz, the perpetually underrated New Jersey rap crew. I remember getting excited when he mentioned Larry Clark's Kids on "Guilty Conscience," back when that movie felt like some kind of nerd secret.

Of course, this was the wrong thing to take away from "Guilty Conscience." This was a major single that got heavy MTV airplay, and it's also a song where Eminem advocates murder and child rape. It was a joke, of course. But this kind of numb shock-value shit isn't funny anymore -- and if you were a person from any sort of subjugated population, it probably wasn't funny then, either. "Guilty Conscience" turns meta when Em makes fun of Dr. Dre by bringing up Dee Barnes' name. At a party in 1990, Dre had severely beaten Barnes, a TV host, slamming her head into a brick wall and trying to throw her down a flight of stairs. Nine years later, Eminem turned her name into a punchline.

The Slim Shady LP is full of moments like this. There are rape jokes all over the album. At one point, he tells a story about using a robotic dick to fuck a woman to death, some real Tetsuo The Ironman shit. In the background, on the ad-libs, he imitates her death-screams. And then there's "'97 Bonnie & Clyde," probably the most disturbing song that I can recite from memory. That's the one where Em explains to his daughter that it's not a big deal that he just murdered her mother. He sweetly baby-talks to her while disposing of her body. Eminem's actual infant daughter cooed all over the song. When Em picked up his daughter to record that bit, he told Kim, her mother, that he was taking the kid to Chuck E. Cheese. They'd only just gotten back together. They'd go on to marry and divorce, and then marry and divorce again.

At the time, even Dre blanched at "'97 Bonnie & Clyde" and at its Marshall Mathers LP follow-up "Kim," telling Rolling Stone, "If I was her, I would have ran when I heard that shit." Marilyn Manson also stayed away. Years later, Manson said that Em has asked him to sing on "'97 Bonnie & Clyde" but that "It was too over-the-top for me to associate with." This is presumably the only time Marilyn Manson has ever said this about anything.

The Slim Shady LP is a complicated album, one that blends pathos and sneery jokes into one big bile-flavored Slurpee. Even on a novelty story-song like "My Fault," the one where Em's date eats too many psychedelic mushrooms, Em can't decide whether to make fun of her or to express genuine terror and regret, so he does both. The level of talent that Em displays on the album -- the rap dexterity, the writerly precision, the general overall charisma -- is off the charts. And yet it remains a tough listen, since the shock-value edgelord nastiness remains such a huge part of Em's persona, and of public life in general. It's the reason being on the internet is such a fucking soul-draining ordeal in 2019. And the success of The Slim Shady LP, and of everything that followed, helped normalize all that. It became mainstream culture.

Eminem was a great rapper, and yet his success turned out to be a bad thing for rap, for society in general, and maybe even for himself. Eminem, an underground insurgent who was still living in his mom's trailer when the album came out and whose stardom must've been beyond his wildest daydreams, couldn't have known any of this when he was making The Slim Shady LP. I didn't know any of it when I was writing those term papers. I wish I'd known. The Slim Shady LP is a classic rap album, and it's also a toxic force. It turns 20 years old tomorrow. It feels like it's a hundred years old, and it also feels like a fresh wound. Happy birthday.

DEAR @NETFLIX,

REGARDING YOUR CANCELLATION OF THE PUNISHER, YOU ARE BLOWING IT!!

SINCERELY,

MARSHALL— Marshall Mathers (@Eminem) February 21, 2019