Paul Huston will always be respected by hip-hop historians and longtime heads for what he can do as a producer. He set a frequently copied precedent for his ability to bring out the inherent uniqueness of the artists he worked with by using a few smartly juxtaposed, expertly chopped, often-unlikely and comedically timed loops and breaks. No matter how drastically he could change his source material from track to track -- 1991's De La Soul Is Dead careened from Tom Waits walking basslines to Serge-via-Stevie lounge-soul to the clacking softshoe of a Harlem Globetrotters "Sweet Georgia Brown" B-side in its first 10 minutes -- each time he'd make that outlandish new idea feel inseparable from the MC's personalities.

But while the sample-genius rep is where he stands as a music-maker, Prince Paul's other big role — whether by the vagaries of the record biz or his own design -- has been as a comrade of the outsider. His first big-deal gig was as the DJ for Stetsasonic, who were already outliers as a hip-hop group with live instrumentation, and he rode with them when they mounted one of the genre's early defenses of sampling as its own art form. His partnership with De La Soul gave the self-described "ultra-nerdy" artists a champion and a mentor when they persevered through the tumult of their first three albums, fighting conventional wisdom as to what and who hip-hop was capable of representing and helping to highlight an idea of alternative rap that still bears fruit 30 years later. And when he hit a dry spell of work in the early '90s, Paul met up with another young industry-soured producer/MC -- one Robert "Prince Rakeem" Diggs -- and by the time they worked out their depression and frustration on the decks, they'd created a slate of beats for their horrorcore crew Gravediggaz that gave the man who would be RZA a new lease on life.

Maybe that's because Paul was so often treated like an outsider himself. By the mid '90s, the Native Tongues movement Paul was so deeply associated with started to fade; De La, A Tribe Called Quest, Jungle Brothers, and Queen Latifah all went on hiatuses of anywhere between 2 ½ to five years after all releasing ambitious albums in 1993. Paul had gone from nabbing Def Jam head Russell Simmons to do cameo duty on "A Roller Skating Jam Named 'Saturdays’" to getting secondhand word from 3rd Bass's MC Serch that Russell thought Paul was "played out" and "wack." And while the Gravediggaz album got him some paychecks, it didn't quell the frustrations. In '96, he figured he might as well just commit messy public career suicide and put out a morbid, parodic, in-joke-crammed concept record about losing his damn mind.

But timing was everything: Psychoanalysis: What Is It? dropped on WordSound in 1996 right when the underground backlash against mainstream hip-hop's excesses was starting to take off. This was the era of Dr. Octagon and The Juggaknots and Company Flow, just a year before the MC who debuted as Zev Love X on the Prince Paul-produced 3rd Bass cut "The Gas Face" started to re-emerge under a mask as MF Doom. Tommy Boy, the label that went from being Paul's first home to freezing him out, liked it so much they wanted to redistribute it. Chris Rock got such a kick out of it that he got Paul to co-produce his 1997 album Roll With The New, extending Paul's capabilities of ruthlessly goofing on mainstream hip-hop to the point where he and Chris started winning Grammys for it. Prince Paul had made it to the other end of a decade that looked like it was leaving him behind, and found himself with a blank check to fulfill his wildest ambitions.

This is where Paul took the idea of his other big contribution to hip-hop -- the interstitial skit, which he popularized on De La Soul's 3 Feet High And Rising in 1989 and had become almost gratuitous in rap albums by the late '90s -- to its most logical and greatest conclusion. If rap was an ideal storytelling genre, and listeners were accustomed to putting up with two-minute stretches of mediocre acting and unfunny jokes between songs on overstuffed CDs, why not do this shit right and get good acting and funny jokes to tell an album-length narrative that defied the skip-track button?

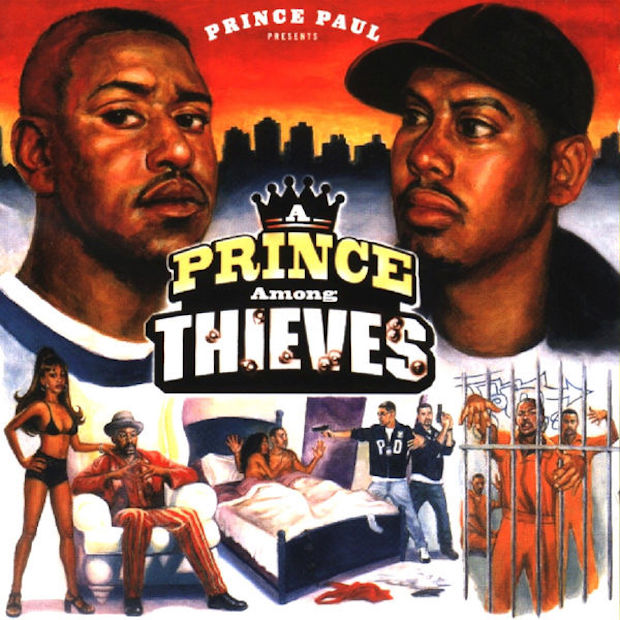

And that's how A Prince Among Thieves, 20 years old tomorrow, came into being. A "rap opera," or in Paul's terms a "movie on wax," had long been simmering as an idea in Paul's mind since the early '90s, and you can hear hints of that ambition on the linking "this album sucks" hater-critique skits of De La Soul Is Dead and the opening courtroom scene of Gravediggaz's "Diary of a Madman," among plenty of other pieces of his production work. But to put together a story that could maintain an entire CD's worth of time meant putting together a simple idea inspired by cheesy B-movies and crime dramas, then finding a cast that could elevate the basic storyline into something special. The narrative itself isn't exactly high-concept: An aspiring rapper needs $1,000 to finish recording his demo tape, a friend of his proposes some easy-money illegal business to make up for that financial shortcoming, and he then gets caught up with gunrunners, pimps, dealers, fiends, crooked cops, prison, and all the social-climbing and backstabbing that comes with it.

The casting was the genius bit. Nearly every rapper on the record -- particularly the vets like Big Daddy Kane, Chubb Rock, and Biz Markie -- were golden era icons who'd been left by the industry wayside or were otherwise considered played out by the post-Coast Wars consensus. A couple guests joined in concurrent with recording their own comebacks. Kool Keith, riding high post-Dr. Octagon, turns in maniacal brilliance as gun dealer Crazy Lou on "Weapon World," and a post-House of Pain Everlast assumed the role of "Officer Bitchkowski" around the time he was cutting his soon-to-be-omnipresent solo debut Whitey Ford Sings The Blues. But on the whole, the album felt like an ensemble cast of veterans spurned by the industry that the album's young protagonist is struggling to break into.

And the voice of that protagonist, Tariq, came from a steadily hustling up-and-comer in his own right. Breeze Brewin', or Breeze for short, had come up with the NYC crew the Juggaknots, and their 1996 self-titled album -- alternately called Clear Blue Skies in honor of their masterpiece storytelling track about a white kid justifying his interracial relationship to his bigoted father -- remains one of the decade's finest examples of uncompromisingly deep underground hip-hop. Taking on the role of an MC desperate to break through and make it big so he can move out of his nagging mom's house isn't quite as challenging a concept, but Breeze pulls it off with charismatic sympathy. He might've been nominally more successful than the hapless Tariq in real life, but even without being hectored by his last-nerve mom or resorting to an associate's criminal tendencies just to scrape up a grand, Breeze had a too-raw-for-radio sense of frankness to him that made headliner stardom seem less likely than a future of cult-favorite underground resilience. But that only humanized him as a character in dialogue and emphasized his personable skill on the mic, making him the ideal straight man in some outlandish Juice/New Jack City environs.

Tariq's foil Tru, meanwhile -- the man who gets him into the business, then into the deep end, before setting him up for a fall and claiming Tariq's demo for himself -- is played with arrogant gusto by Sha, a member of Amityville, Long Island crew Horror City. Paul had originally created a few of the album's beats for a circa-1996 Horror City demo that was never picked up; labels likely took one look at the group's name and expected a diminishing-returns Gravediggaz-esque horrorcore album, even though the theme didn't go any deeper than the group's Jay Anson's nod of a hometown shoutout.

Not only did Paul repurpose some of the beats he made for it -- "Pain," "Put The Next Man On," "You Got Shot," "The Men In Blue," and "MC Hustler" all showed up in prototype form on the demo -- he gave Horror City's other MCs an in with a couple guest spots, including the brilliant goon-rap pastiche "War Party." ("Murder me? You musta never fuckin' heard o' me/ I get thank-you letters from emergency for fillin vacancies.") Sha is a standout as the grimiest of all of them, and when Tariq finally confronts Tru during the climactic "You Got Shot," the contrast between the former's wounded but righteous anger and the latter's bloodthirsty enthusiasm is the kind of lyrical crescendo worth waiting for. But in the end, the bad guy claims the title AND the title track, a disingenuous tribute to the friend he ripped off.

Even if the narrative does overwhelm the production in a way, Paul helms it memorably enough. Not that the beats are slack -- they're just simpler than Paul's more famous supercollages from the early De La days, mixing in a lot of low-key jazz vibes (as in vibraphones, though the atmosphere's a bit post-Buhloone Mindstate in places, too) with some sly nods to pop-R&B of an earlier vintage. "More Than U Know," Paul's reunion with De La Soul, is probably the big standout, even divorced from the storyline structure's depiction of Pos and Dave as prospective crack buyers, introduced by a desperate fiend played by Chris Rock. It's a basic lift of a classic 1983 roller-skate jam anthem, "I Like It (Corn Flakes)" by electro group The Extra T's, but it's such an inspired performance that it belongs on anyone's De La best-of comp. (It also provided a pivot point in one of the best tracks off The Avalanches' Since I Left You, a favor repaid when Prince Paul remixed "Since I Left You" with a Breeze guest verse in 2002.)

Some of the most memorable cuts are frequently referential if not outright parodic. "Steady Slobbin'" is pretty much Ice Cube's "Steady Mobbin'" if Cube was abysmal at sex. "What U Got (The Demo)" calls itself out for flipping Marley Marl's Albert King-sampling beat to Big Daddy Kane's "Young, Gifted and Black" (from the same album, It's A Big Daddy Thing, that Paul himself did two beats for), 10 tracks before Kane shows up as "Count Macula" to sling pimp game knowledge over a tragicomic chop of Hi Records strings and horns. Even some of Paul's older work shows up in the linking skits; that's Psychoanalysis cut/Miami bass parody "Booty Clap" playing in the background as Tariq's mom harangues him on "How It All Started."

[articleembed id="2032858" title="'The Slim Shady LP' Turns 20" image="2032873" excerpt="Eminem came along, flaunting his whiteness and his fakeness, and he instantly became a star. "]

In a year where Paul pulled concept-album double duty -- So … How's Your Girl?, his album with producer Dan The Automator as Handsome Boy Modeling School, would drop that fall -- it'd be tempting to call A Prince Among Thieves the album that renewed Prince Paul's clout in the hip-hop world. It wasn't quite that, though: not content to keep A Prince Among Thieves as a "movie on wax," Paul also pushed Tommy Boy to make it a movie on film, too, getting so far as creating a 9 ½-minute promo clip for a project he considered his own equivalent of Master P's low-budget I'm Bout It (1997). But Tom Silverman didn't go for it, and worse yet, the album itself actually came out a full year after Paul turned in the final product.

A Prince Among Thieves was a solid critical favorite -- #16 in the 1999 Pazz & Jop poll, 10 slots ahead of Eminem's The Slim Shady LP, and just one behind the Handsome Boy Modeling School record. It didn't sell, and it was never really set up to. But at least it was inspirational to Paul in more ways than one: Not only would it stand as one of hip-hop's great underrated classics, the whole experience was the catalyst for another, entirely new concept record four years later. He called it Politics Of The Business, and opened it with a skit featuring Dave Chappelle as a record exec who goes from championing his just-finished, "blazin' like a motherfucker" album to deriding it a year later when it turned out to be "all backpackin' music, you're lucky to go double wood with that shit." The Prince keeps working, but so do the thieves.