In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

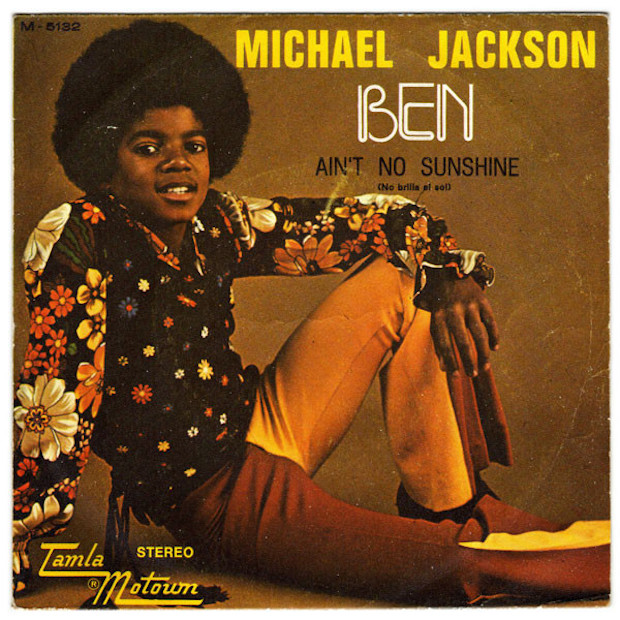

Michael Jackson - "Ben"

HIT #1: October 14, 1972

STAYED AT #1: 1 week

God, I wish I could hear this song the same way again. I wish I could hear any Michael Jackson song the same way again. I'm writing this less than a week after HBO first aired Leaving Neverland, the new documentary about two men who say that Michael Jackson sexually abused them when they were children. The movie is extremely difficult to watch. I've been taking it in in 10-minute chunks, and I'm still not done. Every detail has been sitting with me. There's almost too much to process.

Michael Jackson's story is one we've been seeing over and over again: a famous and powerful person who allegedly used his fame and power to get away with repellant sexual behavior. But because it's Michael Jackson, it takes on a whole new weight of significance. Part of it is that the accusations about Michael Jackson have been out there for more than 25 years, so we've had decades to make whatever mental calculations we needed to make to continue enjoying his music -- calculations now undone by that documentary. Part of it is that Michael Jackson is dead, so it's been nearly a decade since we've had to worry about the idea of a possible abuser benefitting because we wouldn't stop buying his music. But part of it is also that these two men's stories are so sad and moving and believable. And they're believable because it's Michael Jackson.

In the late '80s and early '90s -- the time covered by the documentary -- Michael Jackson could've gotten away with whatever he wanted. He found a level of fame that today's stars can't even contemplate. I was about the same age as the kids in the documentary, and Michael Jackson was the reason I started caring about music in the first place. Bad was the first album I ever bought with own money. I was fully and completely under his spell. In the documentary, we hear from the men (and, maybe more disturbingly, their mothers) about how excited they were to simply be in Michael Jackson's presence, and to experience the dreamworld he built for himself at Neverland. I would've lost my mind to get to do something like that. Michael Jackson had that effect on everyone, but he especially had it on kids. He knew that. And if we believe what's in the movie -- and I do -- he used it.

But Michael Jackson wasn't a pure monster. He had a context. He did not form in a vacuum. His story is complicated. Michael Jackson (allegedly) abused, and he had also been abused himself. He (allegedly) victimized, and he was himself victimized. Jackson's father would beat and whip him, and he would also systematically destroy his self-esteem, calling him ugly so much that he believed it. He was pushed into stardom because he was glowingly, overwhelmingly great at something, and because that something made money. He was globally famous at an age when it would've been absolutely impossible to adjust to that fame. Jackson himself said, many times, that he didn't have a childhood. His defenders make the same point. They're right. Jackson was so good at being a young pop star, and his early records are absolute marvels. Nobody else could've sung or performed those songs the way he did. And yet those records shouldn't exist. The career of the young Michael Jackson is a thing that should not be.

If Michael Jackson really did abuse those boys -- and, again, I believe that he did -- then he owns the responsibility for those actions. But some responsibility also belongs to the parents, and the record labels, that profited from pushing him into this deeply unhealthy life. And maybe some responsibility also lies with us, the people who bought those records, who enabled this entire fucked-up power structure to form. A 14-year-old kid shouldn't have been out there in front of the world, singing a love song to a killer rat. And yet that's "Ben," Michael Jackson's first solo #1.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=cwKWiZAuHoQ

In the 1971 horror movie Willard, the socially maladjusted young man of the title bonds and communicates with rats. A rat named Ben becomes Willard's best friend. Willard's rats take over his life, and then they start to kill the people who have been tormenting Willard. By the end of the movie, the rats turn on Willard, and they eat him alive, as he screams to Ben that he'd always been good to him.

It's hard to comprehend that a movie this weird and unsettling could even exist, but in 1971, it was a surprise hit. So a year later, the world got the sequel Ben, where the rat befriends a bullied little kid named Danny. Ben leads another rat army to protect Danny from his bullies, and Ben and Danny get along so well that Danny makes up a song for Ben -- a song about how they'll always be friends, about how everyone should have a friend like Ben. Then, of course, Ben starts killing people again. They didn't make another sequel.

The lyricist Don Black, who'd co-written a lot of themes for Bond movies, wrote "Ben" with the film composer Walter Scharf. They originally offered the movie's end-credits song to Donny Osmond, but Osmond was touring, and he couldn't record the song in time for the movie to be finished. So it went to Michael Jackson, the kid who'd provided the template for Osmond's career. The Jackson 5's records weren't selling the way they had a few years earlier, so Motown started pushing Michael as a solo artist. And he ended up with "Ben." Once again, nobody could've sung it better.

The funny thing about "Ben" is that the song offers no real indication that it's a song about a rat, though the line about "you're always running here and there" might be a clue. Instead, it's a simple, borderline saccharine song about friendship -- a song with a message pretty close to that of Bill Withers' "Lean On Me," which had hit #1 a few months earlier. The song opens with that same sort of simplicity -- a haunted acoustic-guitar figure and a tender voice. As the song builds, it gets cheesier: cutesy backing vocals, weepy strings, tootling woodwinds. And yet Jackson keeps the song grounded in a way that a more earthbound singer like Donny Osmond never could've done.

As a singer, the young Michael Jackson had this enormously expressive ability to come across as a lost little kid -- quite possibly because that's what he was. On "Ben," he conveys a whole hell of a lot: his tenderness toward this Ben, his naked need to convey that tenderness, his gratitude that he's no longer alone in the world, his heartbreak that everyone else doesn't know a friendship that wonderful. With that remarkably nuanced and emotional vocal, he elevates a song that might've been pure treacle in another singer's hands. It's magical.

"Ben" came out nearly 20 years before the first sexual assault allegations against Jackson hit the news. Jackson presumably wasn't abusing any kids when he made "Ben." And yet the song is now tainted anyway, thanks to the idea that Jackson, at some point in his life, took that incredible communicative ability -- that magic -- and used it to hurt kids. When we talk about cancel culture, about the fog of evil that now surrounds so many once-beloved public figures, it's not about being offended, or about feeling self-righteous because we've successfully demonized these famous people in our midst. It's not about feeling guilty, either. It's about the way joy becomes complicated. To me, at least, it's about how we can't hear these same songs that we once loved without feeling a sinking sensation in our stomachs. And that sensation is now there with "Ben." It'll be there with a whole lot of other #1 Michael Jackson songs, too.

I'm not quite sure what to do with that feeling. In this column, I have given rave reviews to songs that Phil Spector produced, and Phil Spector is an actual convicted murderer. There have been other monsters in this column, and there will be more. (We'll get to R. Kelly when we get to him.) A lot of these people made great music. But there's no way to objectively review music. Objectivity in music criticism doesn't exist. I'm still sorting out how I feel about Michael Jackson, about these songs that I've loved for my entire life. I imagine I'll be doing this for years, maybe for the entire rest of my life. So for now I'll just say that "Ben" is a beautiful song, beautifully sung. And right now, I really don't want to listen to it.

GRADE: 8/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince's beatbox-driven 1987 track "Rock The House," which opens with the Fresh Prince and Ready Rock C doing a routine that interpolates the "Ben" melody:

(DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince's highest-charting single is 1991's "Summertime," which peaked at #4. It's an 8.)

BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's Pearl Jam's 1994 song "Rats," which ends with Eddie Vedder singing a few bars from "Ben":

(Pearl Jam's highest-charting song is their 1999 cover of Wayne Cochran's "Last Kiss," which peaked at #2. It's a 7.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's the incredibly strange character actor Crispin Glover's video for his incredibly strange "Ben" cover, recorded for the soundtrack of his incredibly strange 2003 Willard remake:

THE NUMBER TWOS: Bill Withers' sex-dazed funk hymn "Use Me" peaked at #2 behind "Ben." It's a 9.