Britpop was over. The frenzied moment that had consumed the middle of the decade was in decline, even if not as obviously or tragically as the correlating grunge era had ended across the Atlantic. Through the final years of the '90s, the genre's principal artists were all still releasing colossal works. But whatever cultural movement they had all been lumped into together was waning, each of them wandering off into their own headspaces and abandoning the signifiers and themes that had defined them just a couple years prior. A different chapter was beginning. But, 20 years ago today, one of the era's luminaries released one last wearied sigh, one last fractured document to say goodbye to the decade, to the millennium. Twenty years ago today, Blur released their heartbreak masterpiece 13.

It's not as if British music faltered in the late '90s. It was, if anything, perhaps even richer than the arms race of classic albums that had characterized the zenith of Britpop. But the last few years of the decade were the genre's great comedown period, in which sprawling and strung-out and darkened albums -- albums that were simultaneously more blown-out and more insular and personal -- replaced the panoramic cultural portraits that preceded them. In August of 1997, Oasis released their drug-fueled ego trip Be Here Now. The same year saw masterworks from once-ancillary figures of '90s British music: the turn-of-the-millennium pop of the Verve's Urban Hymns, the turn-of-the-millennium voyages of Spiritualized's Ladies And Gentlemen We Are Floating In Space, the turn-of-the-millennium paranoia of Radiohead's OK Computer.

Several of those albums suggested a new guard arriving to take the reins of British music, but not before Pulp returned with This Is Hardcore in 1998, the bleary soundtrack for the death of Britpop. And if This Is Hardcore played out as a seedy and wearied conclusion to it all, 13 was the beleaguered epilogue a year later: directly birthed from the genre and its era, completely removed from its cultural tropes and aesthetic cues, demarcating the final end of one chapter and the beginning of something else.

Blur had already transformed a couple times over. After being late to the Madchester party, they discovered their voice with Modern Life Is Rubbish, embarking on the Britpop "Life" trilogy that would make them superstars. But after the crystallization of their vision on 1994's Parklife and its lurid endgame on 1995's The Great Escape, they did the unthinkable: They went to America. Having said what they wanted to, they exploded their sound, engaging with Stateside indie styles on their 1997 self-titled outing and, in a roundabout and accidental way, winding up with their most widely recognizable composition in the intended goof of "Song 2."

These predecessors were all aesthetically expansive. But 13 was frazzled and harrowing and adventurous in ways no other Blur album before or since has matched. "This is the sound of someone losing the plot," Jarvis Cocker sang a year earlier, as if summing up the collapse of Britpop for everyone. In 1999, Blur sounded as if they were abandoning all awareness of that plot. 13 was the sound of a band that would never look back.

Of course, there was a plot to 13 -- or, rather, a great deal of narrative surrounding it, which two decades on still makes it a crucial entry in Blur's timeline and in the life of their frontman Damon Albarn. The album, famously, stemmed primarily from the end of Albarn's relationship with Elastica frontwoman Justine Frischmann. For much of the decade, they'd been a Britpop celeb couple, and the final disintegration of their relationship left Albarn wounded and searching. What came out of him and Blur next was a strange mixture, an album that's often downtrodden and defeated emotionally but liberated creatively.

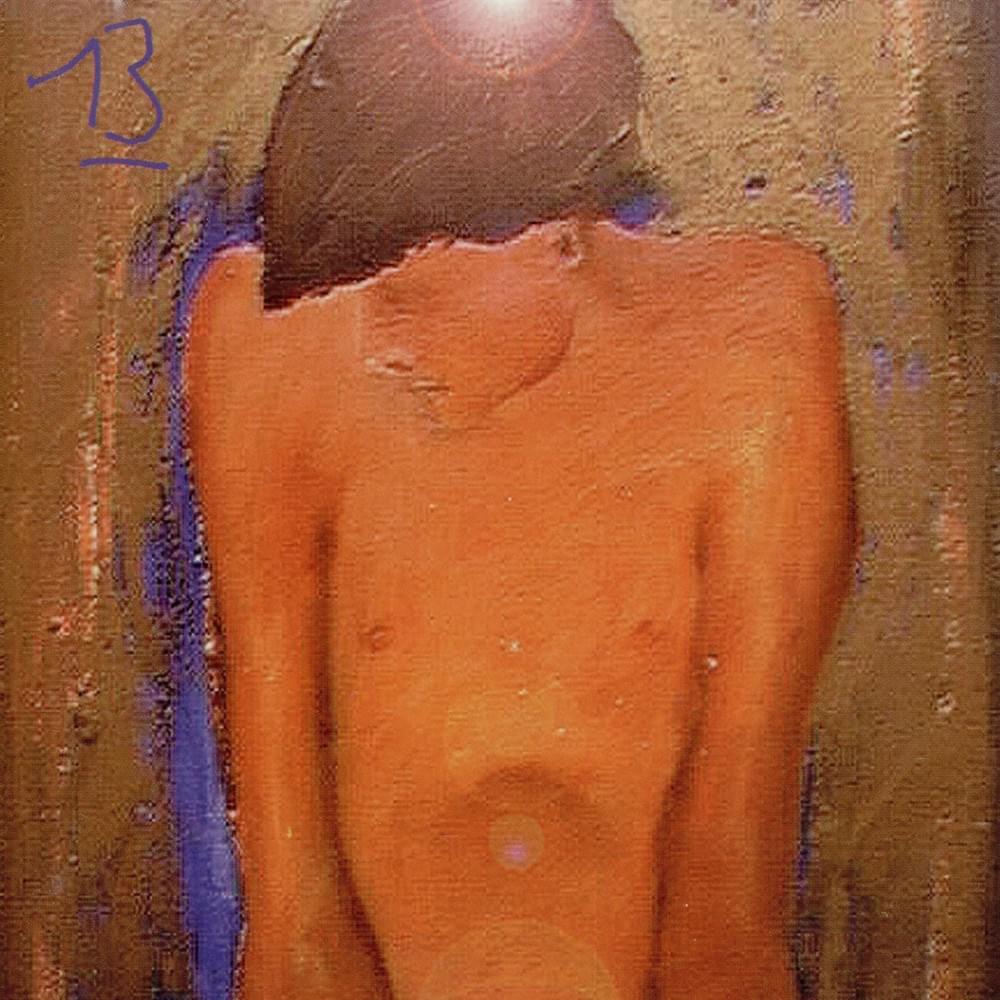

Blur had rendered melancholy beautifully before, especially on career highlights like Parklife's "This Is A Low" and The Great Escape's "The Universal." But those had been installments in greater tapestries, Albarn's kaleidoscopic character studies of British life at the end of a century. He had never written from an explicitly personal place before, and 13 entirely changed this. Reeling from the loss of his relationship with Frischmann, he channeled longing and confusion and pain into songs that themselves were often breaking apart, or into songs that stand as some of the band's most beautiful and heartrending compositions. The band's visual language changed accordingly, too, as they fully abandoned the Technicolor Pop Art vibes of their previous albums for an oil painting done by guitarist Graham Coxon, a painting that communicated the dirty and inward-looking sounds of the album as much as it communicated its blend of physical and emotional hurt.

The whole thing, of course, opens with "Tender." A totemic introduction, "Tender" remains not quite like anything else in Blur's diverse catalog -- a towering Britpop anthem aided by gospel, a lachrymose exorcism that can sound like the lowest point in your life at the same time as it can sound like a true salve. "Tender is the night" are the first lyrics Albarn sings on the album, sharing words with the title of a F. Scott Fitzgerald novel, tapping into the desperate romanticism of another artist with an infamously fractious and public relationship. The song's power is in how Albarn begins alone, remembering a partner who's no longer there and singing paeans to love, and how the instrumentation continues to grow around him so that he is far from alone by its finale. Without any grand sweeping changes, the song gently climbs upwards, the chorus of voices by the end playing out like the healing Albarn pleads for in the lyrics.

If only the journey was that simple. "Tender" is one of the only moments on 13 that approaches true release. From there, 13 fires off in a lot of directions, almost all of them leading towards bleakness. There's the caustic "Bugman," the numbed routine of "Coffee & TV" grasping for the promise of "We can start over again," the throbbing haze of "1992," the spare loneliness of "No Distance Left To Run," effectively the album's closing statement. Perhaps the most striking tracks are "Battle" and "Caramel." Both of them are haunting, spaced-out sagas, perfect representations of Blur's experimental ambitions for 13 and the meditative headspace of the album thematically.

Those latter examples came from another of 13's defining stories, that of heroin use. Hinted at throughout the years, and more explicitly discussed by Albarn earlier this decade, this was an era in which a lot of people in the scene were falling deeper into heroin use. Though Blur had offered narcotic odes before -- like the self-titled's opener "Beetlebum" -- 13 is heroin music almost across the board.

Albarn's been careful when approaching the subject. The creative exploration, the unlocking of a whole new vein of his songwriting at this juncture, he'll credit that to heroin. But it's also a wildly destructive force, one that lends 13 a depressive zone-out sound that once more aligned it with all the great comedown albums in Britpop's final stretch. Like Be Here Now, Ladies And Gentlemen, and This Is Hardcore all did in their own ways, 13 combined a kind of unsexy hedonism with drained emotional landscapes. In the end it proved to be one of the band's more difficult listens, but also perhaps their most rewarding, enduring, and evocative.

13 was, in many ways, the apex of Blur. The band had already restlessly sought out new sounds and ideas in the five albums they'd released in the preceding eight years. And the Britpop albums remain pivotal to the story of '90s England and its music scene. Many fans might still identify one of those as their favorites, and Blur's best songs are fairly evenly distributed throughout.

The nature of 13 demands a stronger connection. British listeners may have related to the scenery of the "Life" trilogy, but 13 is the sort of album that ingrains itself in a person's life, that is there in our own darkest moments. Many of its songs, from "Tender" to "Trimm Trabb" to "No Distance Left To Run," remain amongst Blur's most beloved. And all of these existed on an album that should have sounded scattered and damaged and yet came together into such a moving whole that it seemed, definitively, to solidify the notion of Blur as true artists.

It was, as it turns out, also essentially the end of Blur, at least as we once knew it. When the band reconvened to record another album, the strain of the 13 sessions had left its mark. Coxon soon left the band, leaving total creative control to Albarn. Just as 13 continued the argument that Blur would not just be a pop band from a particular era of British music, the album also marks a major turning point in Albarn's career. After breaking up with Frischmann, he'd moved in with the artist Jamie Hewlett -- a cohabitation that soon yielded Gorillaz. Albarn's songwriting, the ways he could manipulate his voice, would continue to mutate wildly from the adventurous templates laid out by Blur and 13.

By the time Blur returned with Think Tank, sans Coxon, the music was more of a piece with the electronic and Middle Eastern/North African traditions Albarn was exploring elsewhere. Ever since, he has followed through on what 13 suggested. Blur would never look back from here, and Albarn embarked on another two decades of prolific exploration into operas, Afrobeat, more personal singer-songwriter turns, the globally-minded project of Gorillaz for a new digital generation. Even a full Blur reunion -- resulting in 2015 comeback album The Magic Whip -- was the rare occasion in which a band seemed to reappear not when it was convenient or when they'd gotten bored, but when they'd truly come up with something else they wanted to say.

Looking back on it now, that's the mystifying quality of 13. It sits right in the middle of all these conflicts, shrouded with tension. A band and singer broken down, but also set free. An album documenting the collapse of a movement and era, while joining in the murky transitional phase into a new one. An album about losing people and losing a part of yourself in the process, but then also an album about self-discovery. An album about the end of things, that wound up hinting at unlimited possibilities to come. At the time, maybe it wasn't possible to hear that, maybe it just sounded like a more mature and weathered Blur grappling with romantic turmoil. Two decades later, it stands as one of the great albums from the end of Britpop and a key work in Albarn's career. Two decades later, the end of the road can sound like the future at the same time.