Even in their earliest zine interviews, Mogwai had a way of undercutting their own seriousness. In the summer of 1996, when Britpop was still in its heyday, the Glasgow band traveled down to London to play a show at the Highbury Garage, where they also spoke with a fanzine called Algal Zonation. Then still a four-piece, their accomplishments to-date listed in the article included touring with the Pavement-esque Scottish indie band Urusei Yatsura, and guitarist/occasional vocalist Stuart Braithwaite pulling double-duty as the drummer in Eska (another Pavement-esque Scottish indie band). Lobbed some light questions, Stuart often answered first in earnest, with bassist Dominic Aitchison or drummer Martin Bulloch following dryly.

Do you have any interesting or unusual hobbies?

Stuart: Me and Dominic are UFOologists [sic], we drive up a road near us and look for them.

Martin: I play drums.

Where do you get your inspiration from?

Stuart: I would say that I am inspired by things that are original and amazing, anything by My Bloody Valentine…

Dominic: So many things are cool -- having a good day, good clouds, a good cup of tea.

Mogwai's collective sense of humor in those days was not so readily apparent in their recordings. As makers of mostly instrumental rock, there wasn't really a way around that, unless they wanted to follow math rockers Don Caballero and A Minor Forest in giving their long and wordless songs silly titles. Aside from the occasional "I Am Not Batman" or "Mogwai Fear Satan," they hadn't gone that route either. The emotional heft of the rise-and-fall belters that they initially built their reputation on -- early single "Helicon 1," "Like Herod" and the aforementioned "Mogwai Fear Satan" from Young Team, their 1997 debut album -- gave the impression that here were the young men, the weight on their shoulders.

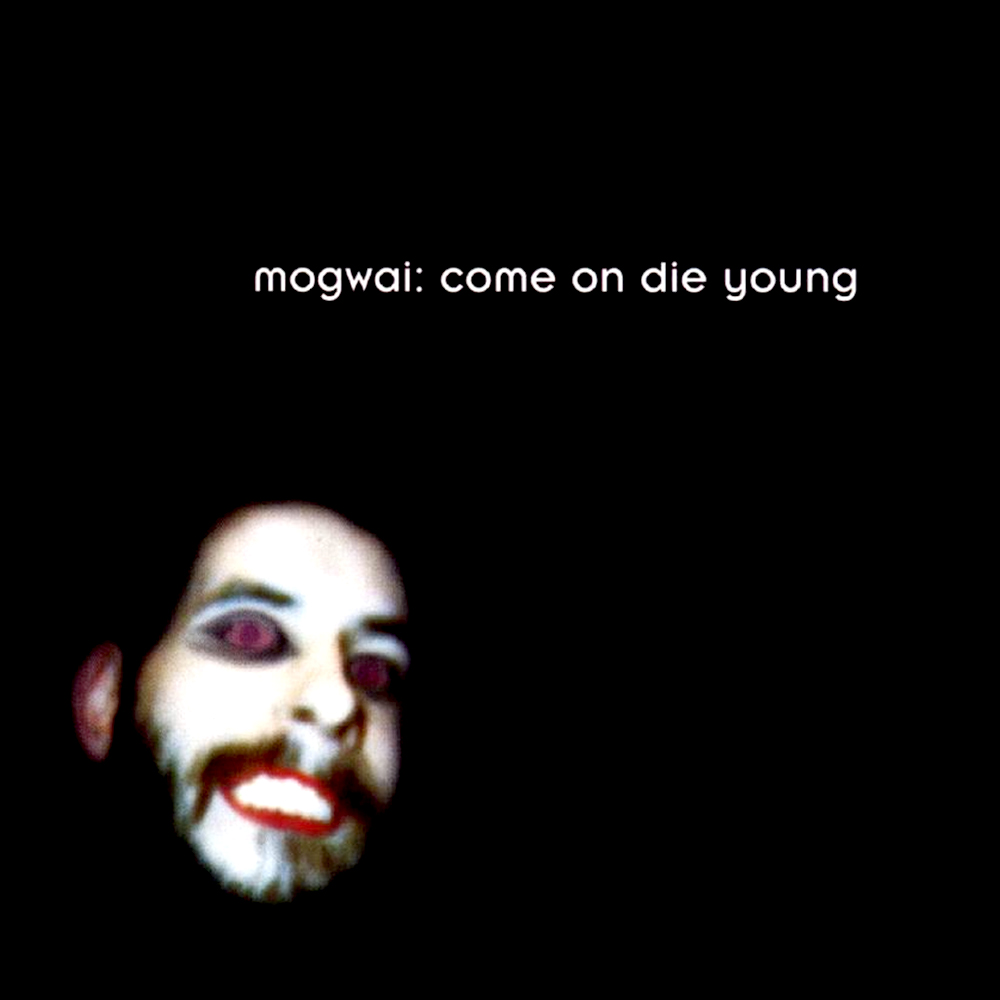

On its arrival in the early spring of 1999 -- 20 years ago today -- the look of their second full-length did little to dispel that image. The cover: stark black, with a small malevolent visage in the lower left corner. The title: Come On Die Young. But the more the eye lingered on it, the more the odd exaggeration of the face (that of Aitchison) started to sink in, with its cartoon gleaming teeth and lips, and the flat purple eyes. The title, like that of their debut album from two years earlier, was a nod to Glasgow's then-pervasive youth street gangs, which were known as "young teams." The references surely went over the heads of many fans outside the British Isles.

In both name and atmosphere, Come On Die Young flirted with menace but defused it in the same stroke. Speaking to the Montreal Gazette in 2003 about how their then-latest album, Happy Songs For Happy People, had previously gone by the working title Bag Of Agony, guitarist John Cummings said he thought they would have ultimately settled on a less humorous title, "...because it's certainly tedious in interviews trying to explain what you meant when you didn't actually mean it at all." He cited a past example: "'Come On Die Young? What, you want people to kill themselves?' Eh, no, not really!" Withholding and nocturnal, Come On Die Young was of a different character than their previous material. When the outbursts finally arrived, they were more abrupt and agitated than the triumphal crests of Young Team. Without much in the way of lyrics to corroborate the mood, the music's intent was left open to interpretation, forcing listeners to look elsewhere for any hints.

Gone from the liner notes this time around were the nicknames that the members of Mogwai had adopted for Young Team, and which reappeared on the UK-only No Education = No Future (Fuck the Curfew) EP in 1998, a 12" which took its name from local graffiti (as did Come On Die Young) that railed against a then-new initiative in the Scottish county of Lanarkshire that imposed a 9pm curfew on those under the age of 16. Now, pLasmatroN, DEMONIC, Cpt. Meat and bionic were back to being Stuart, Dominic, John, and Martin, along with their multi-instrumentalist friend Barry Burns formally joining the fold to make five. A few lines down, though, a curious statement appeared: "mogwai wear kappa clothing."

The credit appeared right below a similar one which read "mogwai use zildjian cymbals," but a drum sponsorship was much more believable. Surely a band of this gravity wouldn't hook up with a company that makes trendy tracksuits? That this was likely a Mogwai in-joke seemed all but confirmed when they upped the ante in the liner notes of their EP + 2 release, which came at the end of 1999: "Mogwai wear Kappa and Adidas clothing. Representatives of Nike, Puma, and Umbro may contact them at the P.O. Box address." Then again, the members of the band could be spotted wearing Kappa clothing around this time, and even included a song called "Kappa" on Come On Die Young.

The casual image such a wardrobe presented did seem to have a sincere appeal to the band. Braithwaite told the Sunday Herald in Scotland a week before Come On Die Young was released, "Our music is so disorganized and unpompous and down to earth...I mean, you wouldn't get ELO wearing tracksuits." (He actually meant Emerson, Lake, And Palmer, but the point was made.) Mogwai dropped the Kappa shout-out after EP + 2, and it was generally assumed that if the affiliation was ever legitimate, it had run its course. Not long ago, Braithwaite acknowledged in an interview that, "It wasn't an official endorsement, but they sent us a box of tracksuits." Last year, Mogwai even paid it forward in a way when they provided band-branded uniforms to a Glasgow primary school soccer team in need.

The Kappa overture wasn't even the only semi-serious fashion statement that Mogwai would make in 1999. More notorious were the T-shirts the band had printed up to sell at that summer's T in the Park music festival held at an airfield north of Edinburgh. Emblazoned with the simple and direct statement that "Blur: Are Shite," the shirts were an amusing punch up at one of that year's main stage headliners. News of the merch circulated in the music press shortly before the festival, and Braithwaite dug his heels in about the assessment of one of that decade's most acclaimed British bands, memorably being quoted as declaring, "It's factual and if there's any legal problems about it I'll go to court as someone who has studied music so I can prove they are shite."

From the vantage point of the present day, it is notable that Mogwai were making these public projections of their slanted sense of humor right around the release of what turned out to be their starkest, rawest album. Even on the record itself, they set up a kind of balance from the beginning. Young Team had opened up with a reading from a Norwegian student's review of a show the band played in that country, which euphorically asserts that "If the stars had a sound it would sound like this," amongst other lofty praise. To set the stage for Come On Die Young, Mogwai turned the mic over to Iggy Pop and the impromptu dissection of punk rock he gave as a guest on a Canadian TV interview program in 1977. Lofty praise was also bestowed in that speech: "What sounds to you like a big load of trashy old noise," Iggy offers after a pause in which he can barely contain his sly smile, "is in fact, the brilliant music of a genius...myself."

Aside from confirming what Trainspotting had already indicated a few years before, that Scottish rock culture had a deep and abiding love of Iggy Pop, the deployment of this monologue to open up Come On Die Young was strategic. It connected in listeners' minds the principles of punk rock with the spacious, clanging hour-plus of (mostly) instrumental music that was about to follow, and also defused any prior impression that Mogwai might be a touch too self-important. The songs were unhurried, and in the second half their lengths began to kiss the ten-minute mark, but this was not intended to be ponderous music. "There were a lot of ideas on the first record; it was overloaded with them," Braithwaite told the Sunday Herald, "so we decided to be a bit more subtle. It's the difference between how fast you ride your bike and how slow you ride it -- it's always harder to ride your bike slow."

"Punk Rock" premise in place, Come On Die Young then lurches into its acronym title track, "Cody," where Braithwaite gives his first up-front vocal performance. The song is a weary sigh beyond the band's years at the time (they were in their early twenties), lacing laments for old friends and sad songs together with searching lap steel played by guest musician Richard Formby. "And the way that it is, I could leave it all/ And I ask myself, would you care at all?" made for a drastic pivot from Pop's righteous soliloquy. Those were also the last intelligible words that listeners were left to go on; for the rest of the record, they were on their own to contend with its meaning.

What do Mogwai follow the slow motion heartbreak of "Cody" with? The sound of a football game broadcast on television. Once again, they are quick to chip away at their own heaviness. "Helps Both Ways" bleeds into "Year 2000 Non-Compliant Cardia", which bleeds into "Kappa," which bleeds into "Waltz for Aidan." Track divisions on the first half of the album can feel almost arbitrary, and to a distracted ear the sequence could easily be mistaken for one long piece of music. Braithwaite recalled that early on in the recording process they realized all the songs were in a minor key. Mogwai were also making a conscious effort to move on from the quiet/loud dynamic that they were already concerned about getting stuck in, but that dynamic was still very much a part of their DNA. Come On Die Young is hardly quiet/quiet; Bulloch's drums, for one, are abrasively front-and-center throughout, especially in that early stretch.

Mogwai traveled all the way to upstate New York to record with Dave Fridmann at his Tarbox Road Studios in rural Cassadaga, where they seem to have put the high ceiling of the main recording room to use. The cold abandoned warehouse vibe probably would have come through no matter where they recorded the album. Still, Fridmann brought a subtle warmth to a set of songs that were drawing inspiration from the Cure's goth years and the artsier edge of American underground rock. This was when the "children of Slint" comparisons started to appear, but surely Come On Die Young helped sell a few copies of Spiderland as well.

Fridmann, having recently steered the lush psychedelic achievements of the Flaming Lips' The Soft Bulletin and Mercury Rev's Deserter's Songs, made for a good choice of producer in this regard. Though Braithwaite would state that the decision to record Come On Die Young where they did was also driven by the more grounded motive of placing themselves somewhere free from distraction where they'd be forced to focus, the insight and supplemental instrumentation that Fridmann brought to the table helped fill it in. Though the unadorned aggression of some of the music may have seemed more a fit for a producer like Steve Albini (who the band would connect with a couple years later for the ridiculously long, crushing "My Father My King"), Come On Die Young was already skinless and on edge enough, it didn't need any help in that regard.

Come On Die Young tries to hold back as long as it can, but its grip loosens through the second half. Song lengths suddenly double; "Ex-Cowboy," "Chocky," and "Christmas Steps" clock in at a combined half hour of the total running time. The penultimate "Christmas Steps," a re-recorded version of "Xmas Steps" from the No Education EP, is positioned to be the climactic wait-for-it noise release, but when the moment comes, even that song proves to be more of a steady builder than a dive off a cliff into seas of distortion. Come On Die Young winds down having never fully shaken its feeling of being pent up, never fully stepping out from the unnerving shadows that surround it.

Mogwai's reputation-cementing opus to the beauty found in gloom ends -- how else? -- with a slight return to the opening ceremony, titled "Punk Rock/Puff Daddy/ANʇICHRISʇ." Absurdist song titles remain a hobby for the band ("Don't Believe the Fife" from their 2017 album Every Country's Sun is a recent winner), but that one might still top them all. Though they have long since toned down their rock culture rhetoric in interviews, and have gone on to establish themselves in the respectable realm of film and television soundtracks, their instinct for in-jokes hasn't been completely repressed. "We take our music pretty seriously," Braithwaite said in 2001, "but we've never taken anything around it particularly seriously." Never was that more true than in the Come On Die Young days.