There's a point in many young rappers' lives when they become infatuated with MF DOOM. Joey Badass mined volumes of Special Herbs compilations for beats on his debut album. Milo scoured filesharing service Kazaa to find DOOM loosies in his pre-highschool years. Odd Future compatriots Tyler, The Creator and Earl Sweatshirt looked like toddlers meeting a mall Santa when they came face-to-mask with the rapper in 2013. DOOM's left his metal fingerprints all over alternative-minded hip hop, and has inspired artists of all stripes to mask their identities over a two-decade period in which the concept of a"private life " has all but disappeared. For these reasons, DOOM's often deemed influential -- rightfully so, just based on how many artists cite him as formative to their careers. But apart from an assonance-laden non-sequitur here and an anonymous identity there, is anyone really imitating his singular career path? In our extremely online era, can anyone imitate it?

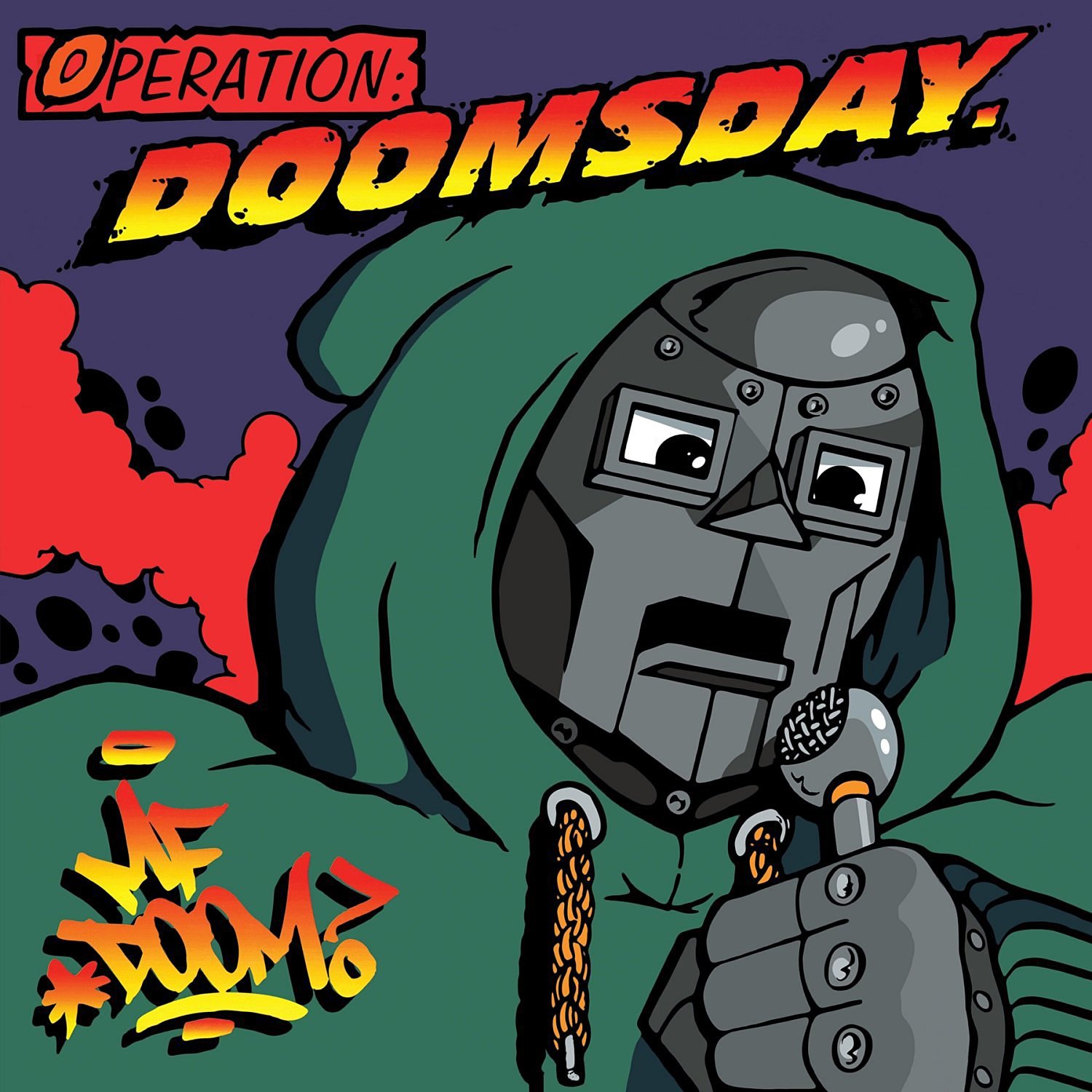

Twenty years ago this weekend, DOOM released his solo debut, Operation: Doomsday. It's an immediately engaging display of his raw talent as both a rapper and producer, as well as an engrossing origin story for the most popular of his many alter-egos. But looking back on the circumstances preceding Doomsday's releaseand the cult success story he became, the thing I can't shake is how impossible it would be to recreate DOOM's early career path in 2019. His rise is inextricably linked to a specific moment in technological, cultural, and rap history. I'm not so much talking about surface-level concerns like the popularity of boom-bap or the logistics of sampling the Beatles'"Glass Onion, " Steely Dan's"Black Cow, " and the Scooby Doo theme on a no-budget indie album. It's the late '90's radically different industry politics and hype machine that played much larger roles in how DOOM came to be.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Before he was DOOM, Daniel Dumile was Zev Love X of the wildly underrated Long Island trio KMD. Why are they underrated? Their 1991 debut, Mr. Hood, is good enough to nestle in alongside albums by the neighboring Native Tongues collective as a sterling example of posi-vibes East Coast rap, but its far darker, more complex follow-up never received the release it deserved while KMD were still intact."If Black Bastards had come out in 1994, I think it would have been a huge underground classic, " 3rd Bass member and early Dumile collaborator Pete Nice once said of KMD's sophomore album. Unfortunately, a few Billboard writers misconstrued its cover art and made the album an unmarketable pariah. Columnists Terri Rossi and Havelock Nelson seemed to think KMD were depicting the lynching of a offensively-rendered black man. In reality, it was intended to be a white man in blackface."If it was anyone being hung there, it was Al Jolson or Ted Danson, doing that stupid shit he did, " said DOOM in a later interview, referring to two prominent perpetrators of blackface.

Had Rossi and Havelock actually listened to Black Bastards, they may have still been shocked by an angrier, more violent album than Mr. Hood, but there's no way they could've construed its candid discussions of racism as anti-black. Their outrage around the artwork effectively blacklisted the album and prompted Elektra to drop the group. A few years ago, DOOM cited the much-publicized outrage over Body Count's"Cop Killer, " released a year prior, as the label's cause for caution, but also added,"I think it was more like, 'Is this product marketable? Can we sell it?' If they'd found a way to sell it, it wouldn't have been a problem. "

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

These days, we're lucky enough to see most albums that prominently protest racism or bigotry elevated into the spotlight. To Pimp a Butterfly, Lemonade, A Seat at the Table, DAMN., and Dirty Computer are some of the most acclaimed albums of the last five years, and while all are decidedly more sleek and shiny than the grimy, haphazardly-mastered Black Bastards, there's still plenty of praise for similar rhetoric in a thriving underground populated by artists like Earl, JPEGMAFIA, Open Mike Eagle, and Armand Hammer. It's almost impossible to envision an album as wittily political as Black Bastards -- let alone any album -- getting shelved because of its artwork in 2019 (see: Pissgrave's gruesome Posthumous Humilation warranting a Pitchfork review earlier this year). It's also insane to imagine a time in which Billboard writers wielded the power to effectively end artists' careers.

Suppose we consider Elektra only gave up on KMD because they weren't bankable enough. Had the group come out a few years later, they would've had a vibrant collection of indie rap labels to fall back on. Black Bastards would've been right at home on Stone's Throw, Babygrande, Rhymesayers, or especially Def Jux, but none of those existed in '94. Any cultural cachet that's now associated with jumping down from a major to an indie in order to release grittier material didn't really register during the commercial gold rush of early '90s rap.

The fact that Black Bastards was a"lost " album until its eventual release in 2001 added to the mystery surrounding Dumile, as did the sudden and tragic death of his brother and fellow KMD member DJ Subroc. The details on DOOM's life between '94 and '99 are murky at best, thanks in part to DOOM himself, who's fluctuated between saying it was a"really, really dark time " during which he was"damn near homeless " and on other occasions, claiming that he was"just doing regular stuff, just raising my son. " Not to go too deep into a parallel universe here, but had Black Bastards gotten its due, it would've been much harder for Dumile to disappear, and he probably wouldn't have faced near-homelessness.

People close to Dumile often cite this dark period as the reason he created the MF DOOM character, an amalgam of Fantastic Four villain Doctor Victor Von Doom, G.I. Joe villain Destro, and the Phantom of the Opera (according to DOOM). Blake Letham, AKA KEO, the visual artist who helped DOOM design his now-iconic mask, has noted that his friend was"disgusted with the whole industry for a while. " Dante Ross, the Elektra A&R that signed KMD, said that,"Sub[roc]'s death, understandably, made DOOM a very angry person. "

Upon his return to music, anonymity was DOOM's main goal."In the beginning he'd throw on a bandana, or whatever he had to do, " said Letham,"the idea was to conceal his identity. " Not only did this goal manifest itself in his physical presentation, but also in his adoption of fictionalized characters and constantly-shifting narrative perspectives in his music, and in how he chose to release his first solo music. Between 1997 and '98, Dumile released three nondescript 12 " singles -- all of which would later appear on Operation: Doomsday -- on Fondle 'Em, a tiny label started by NYC hip-hop legend Bobbito Garcia."I think DOOM enjoyed putting out stuff the way we did it, with no politics or any of that, no record sleeves, no CDs. " Garcia said of those inaugural releases."Just put the record out and it will speak for itself. "

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Those singles weren't widely distributed, and at least initially, neither was Doomsday."It's the epitome of underground labels, no promotion, " said DOOM in a 2001 interview."The album did get to Germany, to certain select places in Cali, but it didn't get the widespread availability it could have had at the time. A lot of people couldn't get it."

For that reason, most people's first experiences with DOOM lacked context."Man, it must've been great to hear all this music chronologically as it was happening, " remarked rap critic Andrew Nosnitsky in an NPR segment on Black Bastards' 20th anniversary, with interviewer Eric Ducker citing how difficult it initially was to"reconcile how the bookish and playful young Muslim guy in KMD went on to become this demented street super villain character named MF DOOM. " Milo noted that in his earliest experiences with DOOM, he was,"hearing stuff from Madvillainy next to Operation Doomsday next to some KMD track. " Those guys have either a few years or a few volumes of rap knowledge on me, so my introduction to DOOM came much later, but it was no less mystifying. When I heard Cee-Lo's hook on DOOM and Danger Mouse's"Benzie Box "- --"His name's DOOM/They wonder just who is he " -- I had to know more.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

If we moved DOOM's timeline ahead 10 or 20 years, I would know more. Even if the same fate somehow befell Black Bastards, there'd be more attention paid to his juicy, redemptive narrative. Even if he went to the same lengths to achieve anonymity, he'd be quickly sniffed out like Earl in Samoa or Rick Ross' past as a corrections officer. Even if he still envisioned a no-frills release strategy Doomsday, it'd be more readily available to the public, probably wouldn't be released on a radio DJ's tiny indie label, and almost certainly wouldn't be a label's first-ever full-length.

The most inimitable aspect of DOOM's rise, though, is its word-of-mouth spread. In the NPR interview, Nosnitsky poetically sums it up:"secrets could still move slowly back then. " Most breakout stories and career trajectories in music 20 years ago would play out completely differently in 2019, but DOOM's is one of the few that looks irretrievably encased in amber.