On first pass, "Army" seems like your standard Ben Folds class clown routine. His voice drops in out of nowhere -- "Well I thought about the army/ Dad said, 'Son, you're fuckin' high!'" -- and we're off to the races. Robert Sledge's overdriven bass melody surges beneath Darren Jessee's bopping beat, Folds unspools some madcap piano theatrics, and before you know it a buoyant brass section is enthusing along with them. Like many Ben Folds Five songs, it's a hell of a lot of fun. Except if you pay attention to the lyrics, it's actually a terribly depressing narrative about the various failures throughout Folds' life.

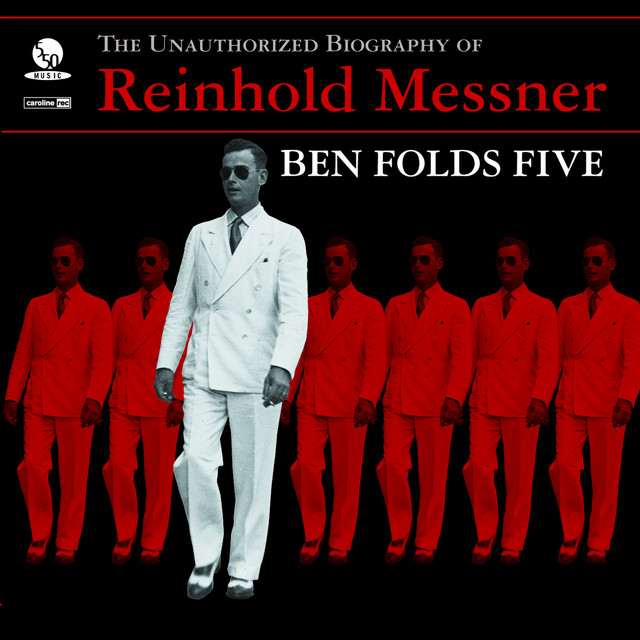

The "Army" narrator drops out of college after spending $15K on "three sad semesters." His band breaks up and reforms without him a month later. Multiple ex-wives despise him. According to Folds, the song is an essentially accurate retelling of his life. He really did go to college after his dad discouraged his enlistment idea, only to flunk out in debt. His band Majosha really did break up in 1990, after which several members, including Folds' own brother Chuck, started a new band called Bus Stop without him. He really was two divorces deep by 1999, when "Army" became the lead single from Ben Folds Five's The Unauthorized Biography Of Reinhold Messner. (It turns 20 years old this Saturday.) So even if "Army" is jubilant and even euphoric at times, it feels most honest when all that bombast scales back and Folds plaintively confides, "Been thinkin' a lot today..."

He was apparently spending a lot of days like that in the lead-up to Reinhold Messner, the last of Ben Folds Five's original trilogy of albums. Anger, frustration, sadness, resentment, and self-doubt had been cornerstones of the first two Ben Folds Five LPs, but on those records Folds often channeled his negative emotions into comedy. By updating classic piano-pop into a '90s context and forbidding guitars, he and his bandmates had carved out a unique place within alternative rock. Taking cues from ivory ticklers across the 20th century -- Rodgers & Hammerstein, Paul McCartney, Elton John, Billy Joel -- the Chapel Hill trio wrote sing-along anthems founded in instrumental virtuosity, sometimes scathing and sardonic, other times doe-eyed and sincere. On the band's 1995 self-titled debut Folds was the lovable wimp, and on 1997 breakthrough Whatever And Ever Amen he was the vengeful dork. As he worked through his traumas from childhood up to the present, even his most melancholy moments emanated a "gee-whiz" quality. Even the band name was a joke.

Reinhold Messner was different. The same musical muscles were being flexed, but this time everything was heavier and more serious. Folds seemed to be walking around in a fog. Maybe the success of "Brick," Whatever And Ever Amen's solemn abortion ballad that broke out at MTV and become the band's signature song, had convinced Folds to lean into his dark side. Maybe he was tired of being perceived as a cloying jokester and wanted to rebrand himself as a serious artiste. Or maybe he just couldn't laugh off whatever was gnawing at him anymore. Whatever the reasons, the third and final collection from Ben Folds Five's initial run was submerged in shadows. "Army" was the obvious single because not only was it a phenomenal pop song, it was the only tune on the album that didn't sound like a resigned sigh -- and even "Army" was ultimately a lament.

This should in no way be read as a dismissal. All three of those Ben Folds Five albums are great in their own way. The debut established a compelling template and contains some moments of pure inspiration; despite some undercooked moments, you can sense the band's thrill at the sound of their ambition coming to fruition. Whatever And Ever Amen, while sometimes off-putting in its unchecked vitriol, improved on that template and is probably still song-for-song the strongest collection of Folds' career. I consider it a classic, but I never got around to celebrating its anniversary for reasons I can't recall. So instead here I am revisiting the weird, sad, underrated curiosity that for years served as the band's swan song.

Reinhold Messner was a real person, the first mountaineer to scale Everest without the aid of artificial oxygen, but the band was unaware of him when they named their album. His name also proliferated on fake IDs around Houston when drummer Darren Jessee was growing up, which made it an esoteric way to introduce the project's self-examination. Even knowing the context, it's a bit of a misnomer. Folds had already been interrogating his adolescence on the band's two prior albums, and although he continued to do so here, the album feels preoccupied with more adult concerns, from regret and loss of innocence to hospitalization and death.

In parallel, the music is statelier and more sober. Reinhold Messner errs closer to chamber-pop than anything else the group ever recorded. It begins with the perverse and wildly satisfying "Narcolepsy," a proggy epic that merges the band's usual piano rock with neoclassical orchestration. As movement after climactic movement unfolds, Folds describes falling asleep involuntarily while his lover cries streams of tears. The big finish builds in intensity as Folds repeatedly insists, "But I'm not tired!" He designed the tender breakup ballad "Don't Change Your Plans" to be just as grandiose, but producer Caleb Southern convinced him to chop off a long instrumental passage up front, leaving behind a wistful beauty of a pop song that ranks among his finest work. Overflowing with gorgeous flourishes, it's basically '70s sitcom theme music. It drifts like the breeze until it soars like the wind, carrying Folds away from someone he loves for reasons he can't fully explain.

Things get even sadder with the rhythmically charged "Mess," with its dejected chorus: "And I don't believe in God/ So I can't be saved/ All alone, as I've learned to be/ In this mess I have made." He remembers a dead friend on the tearjerker "Magic" and questions some diagnosis of his own on the drowsy "Hospital Song." After the deceptively upbeat "Army" comes a couple epilogues of sorts: The jaunty "Your Redneck Past" plays like one of McCartney's "Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da" goofs, while the meandering lounge groove "Your Most Valuable Possession" pulls the voicemail-from-concerned-parent trick years before Frank Ocean did it. He continues to spell it out plainly on "Regrets," which sets a range of sour memories against brisk jazz fusion that might otherwise soundtrack metropolitan life in a movie scene.

The project ends on a more positive note, first with the easy listening encouragement note "Jane" and then with the gentle and optimistic "Lullabye." Folds recalls being sung to sleep on a flight as a child: "Goodnight, goodnight sweet baby/ The world has more for you than it seems/ Goodnight, goodnight/ Let the moonlight take the lid off your dreams." After so much woeful pageantry, it's unclear whether we're to receive this flashback as a cleaning of the slate or an ironic callback to a clearly off-base prediction, but given Folds' saccharine tendencies and the song's reverent tone, I suspect it's the former.

The future Folds had to look forward to in reality was Rockin' The Suburbs, a solo album that blew up commercially by blowing out all his most accessible impulses. That one set the stage for a long and varied career, cheesier and more sentimental than Ben Folds Five's and seemingly more profitable too. Folds has penned many a mushy ballad since then -- including several on Ben Folds Five's 2012 reunion effort The Sound Of The Life Of The Mind -- but never has he sounded crushed under the weight of life like he did on Reinhold Messner.

In hindsight, the record's pessimistic tone feels like a band accepting defeat, but at the time Folds had high hopes. As he told an iTunes interviewer years later, "I think in a way it shows how naïve we were, and idealistic we were as a band to think the music business would care about us extending ourselves and developing and being something different, because that record was a failure -- in almost every way that you can fail. As a commercial release, it didn’t sell up to anybody’s expectations; critically, it got sort of lukewarm reviews; and yet, I think that was our best work. I think it’s a great record."

This album about failures, then, is in one sense another failure to add to the pile. Except Reinhold Messner really is great. It truly did deserve more attention upon its release. Is it Ben Folds Five's best work, as Folds believes? Probably not -- too many dreary passages interrupting the bursts of magnificence lend the album a musty quality that usually has me skipping around. Listening straight through tends to leave me in the doldrums, and there are moments -- like the big earnest "sha-la-la" climax on "Magic" -- where what should be high drama hits more like goopy melodrama. But if it's not the group's greatest achievement, it is undoubtedly their most audacious and ambitious creative statement, the kind of bold chapter more discographies could benefit from. So even though it's an overwhelmingly sad record, in the big picture it leaves me feeling glad. Folds could have joined the army. Instead he made this.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]