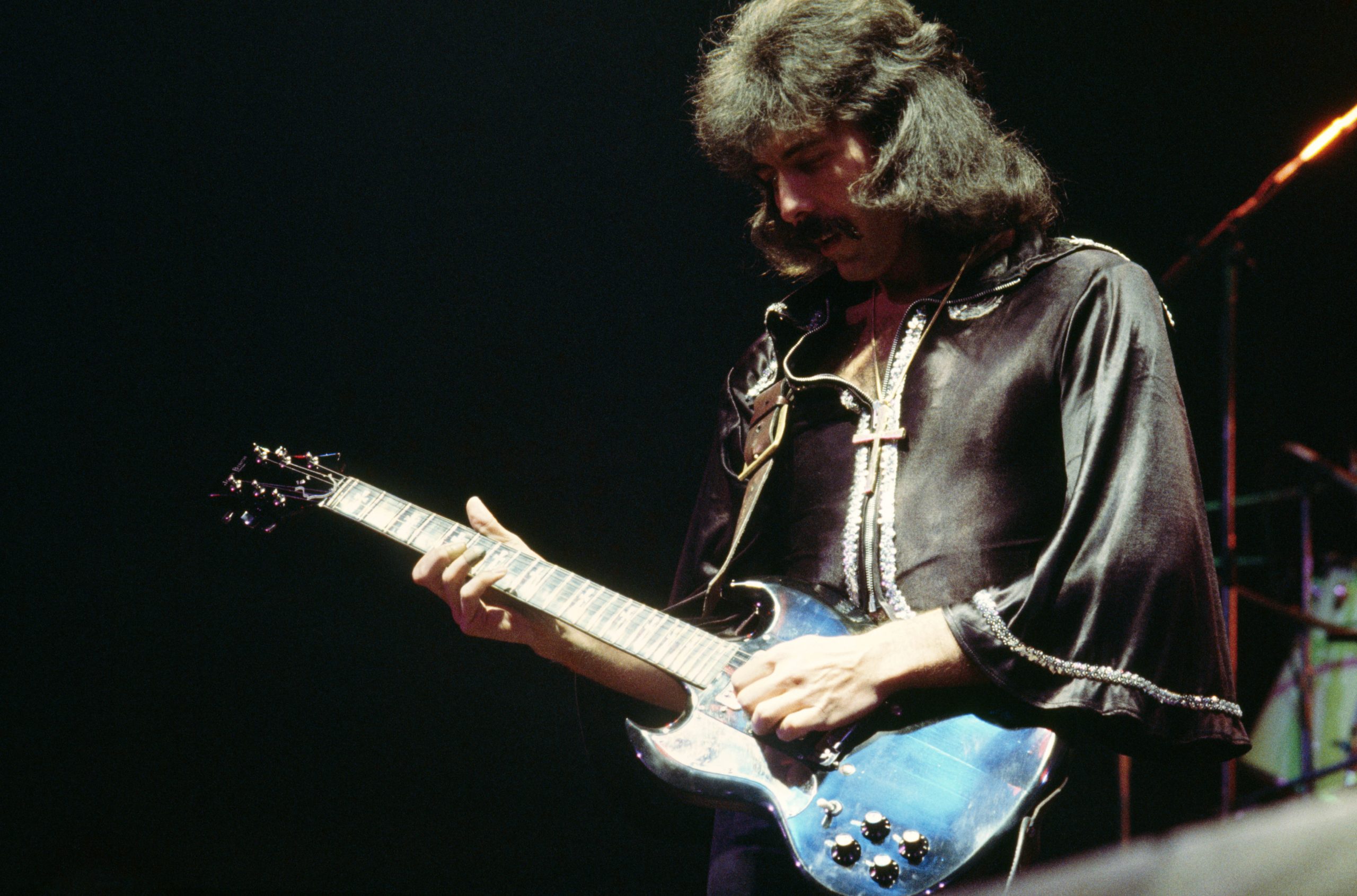

When you're a metal god, people want to know about the time you lost your fingers. "One day, the person that would be sending me the thing to weld never turned up, so they put me on this giant, huge press -- a guillotine-type press. I don't know what happened, I must have pushed my hand in," Tony Iommi said in an interview with Loudwire's Ryan J. Downey at the Musician's Institute in 2017, recounting a particularly gnarly 'I'm not even supposed to be here today' incident at the industrial factory he worked at when he was 17. "Bang! It came down. It just took the ends off [my fingers]. I actually pulled them off. As I pulled my [hand] back, it sort of pulled them off. It was left with two stalks; the bone was sticking out the top of the finger."

As the story goes, detailed further in a 1997 Guitar World Online column, his friend and foreman played Django Reinhardt for Iommi while the teenager was convalescing and coming to terms with the medical prognosis that his once-promising guitar career was on indefinite hiatus. "You know, the guy's only playing with two fingers on his fretboard hand because of an injury he sustained in a terrible fire," Iommi remembers the friend saying, likely while the spirit of Reinhardt shredded through some gypsy swing that still challenges those with full complements of phalanges.

Inspired, the future Black Sabbath guitarist developed a number of innovative methods to work around his injury, perhaps influencing the sound and style of the genre he'd soon father in the process. That's the popular myth, anyway. The man himself was a bit more regretful when speaking to Team Rock in 2016, not quite aligning with the all's-well-that-ends-well legacy that has been applied to him: "I would have liked to have not chopped the ends of my fingers off. It became a burden. Some people say it helped me invent the kind of music I play, but I don't know whether it did. It's just something I've had to learn to live with."

That last line might as well be the refrain of musicians who have been forced to take a detour onto the road to recovery. And that might be most musicians. Given the fallibility and fragility of the human body, it wouldn't be a surprise to find that many have been afflicted by an injury that has inhibited or curtailed their playing.

What is surprising, though, is the number of musicians who have reported injuries either caused by playing or whose preexisting injuries have gotten worse due to the normal, expected demands of the trade. An oft-cited 2012 study by Prof. Dianna Kenny and Dr. Bronwen Ackermann of "professional orchestral musicians in Australia" found that 84 percent of those surveyed suffered playing-related injuries. Granted, the majority of these injuries aren't as dramatic as Iommi's day-job dismemberment, such as the varying gradations of common repetitive strain injuries, but they're still debilitating, mentally taxing, and possibly life-altering.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

The video above is pulled from Troy Tipton's contribution to the Chops from Hell instructional series. Along with his brother Jasun, Troy would push the technical limits of progressive metal in Zero Hour. Each album increased the band's exposure, earning the quartet critical raves. Nevertheless, at its peak, Troy started experiencing issues with his elbow. "Basically, his ulnar nerve was crushed with the bone because he was doing bicep curls," Jasun said in a Sonic Perspectives podcast last year. "And what ended up happening, he wasn't getting any circulation and the nerve itself was just not generating. So, he was losing all feel."

By Jasun's account, Troy persevered, recording the band's 2008 album Dark Deceiver right on the heels of a busy touring schedule. The plan was to head back out to hit some more festivals, but due to the structure of his insurance plan, Troy needed to schedule "ulnar nerve entrapment surgery" (known as "cubital tunnel release surgery" in some literature) following his doctor's emphatic recommendation. He went under the knife. And then came the aftermath.

"Troy did his best and everything to try and make things work," Jasun remembered. "Every time he took a step forward, he was taking two steps back. Literally to the point where his left [hand] was just falling off the fretboard, man."

After speaking with other providers, Jasun believes that ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction (also known as Tommy John surgery, baseball fans) would've been a more successful procedure. But what was done was done. Without Troy at full capacity, Zero Hour split. To his credit, he'd eventually lay down admirable contributions for Abnormal Thought Patterns and Cynthesis before transitioning to vocals for the Tiptons' new project A Dying Planet. The band's debut, Facing the Incurable, was released last year. It opens with the 14-minute "Resist," featuring guest vocals by Paul Villarreall. Here's a snippet of the lyrics:

A ligament thickening

Dysfunction and tingling

Compressing excessively

The pain is so unreal

I'm suffering physically

It's mentally

Mentally draining

Free me from this agony

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

While something of a worst case, Jasun's retelling of Troy's story is not unique, sharing familiar beats with others that have been published over the years: the intense habitual workload that leads to injury, difficulty of finding musician-knowledgeable medical help, and psychic toll of losing your grasp on what you've worked so hard to achieve.

"Your value as a musician depends on your ability to play at a high level," guitarist David Sobel said in a piece in Johns Hopkins Magazine that profiled Dr. Serap Bastepe-Gray, underscoring both the common cause and psychological aftereffects of musician injuries. Sobel's injury was due to overuse, born out of constant practice and playing in order to master his beloved craft and further his career: "I was that starving musician who can't pass up a $100 gig."

But it's not just the gigs that cause injury, it's what happens in between those gigs, too. For the CBC, Claire Motyer asked physio/massage therapist Pauline Beaud about the root causes of overuse for a piece exploring why students were dropping of music schools:

Some risk factors she identifies include: inadequate knowledge of the body and how to lead a healthy lifestyle; anything putting more stress on the body, such as posture, technique and inadequate practice breaks; consulting a health practitioner too late; and environmental or emotional stress.

If it reads like simply being a musician is a risk factor, that echoes what violinist Reinhard Goebel told The New York Times in 1996: "Being a musician can be an accident." Writer James R. Oestreich clarified: "What he seemed to mean was, 'Being a musician is an accident waiting to happen.'" And it does feel like there's a devil's bargain that takes place somewhere along the traditional path to success: that the harder you work, the more likely you are to unintentionally shorten your career. But, then again, you don't know you're going to get injured until you're injured.

To that end, it's hard not to wonder how metal's specific set of risks stack up. For instance, metal's twin motivators of escalating extremity and unceasing progression mixed with it being, generally, a young person's DIY genre on a shoestring touring budget seems like a particularly volatile combination. From an anecdotal perspective, a young metaller probably doesn't spend too long thinking "I could practice with proper technique to protect my future health" before straining to learn "The Trooper" alone over summer break. Unless someone tells you otherwise, feeling that resulting dull ache is a rite of passage, a signal to yourself that you too are willing to silently suffer for your art like those who came before you. The downsides are years away until, suddenly, they're not.

In a great piece written by Andy Hermann for LA Weekly, Jill Gambaro, whose book The Truth About Carpal Tunnel Syndrome still sits in Amazon's "Repetitive Strain Injury" charts, was attempting to get musicians to consider the long term. "With repetitive strain injuries, the more you do something, the worse it gets," Gambaro said at a conference. "It's so easy to ignore and I'm asking you please, don't do that, because your body's trying to tell you something." The tricky part, though, is undertaking preventive measures when you feel fine.

"Many musicians understandably have an 'if it ain't broke, don't fix it' mentality when it comes to practice and performance routines," wrote Dr. Jonathan Kretschmer, PT, DPT, MM in an email to me. "After all, their routines have made them, in many cases, great players. Unfortunately, sometimes those routines lead slowly and inexorably to injury, and problems can crop up quickly without much warning."

Kretschmer, who runs the musician-focused physical therapy website PTformusicians.com, not only has the medical credentials to back up his expertise, but the music background. Before physical therapy, he was a Juilliard-trained trumpet player who played in many symphony orchestras. After suffering an embouchure injury, he rehabbed with David Shulman, PT, a noted therapist who has been working with musicians since the 1980s. Per PTformusicians.com's "About" section, the "experience was a transformative one," and soon Kretschmer would begin his next career as a medical provider. From 2015 through 2018, he'd also develop and teach Health And Wellness For The Musician at the San Francisco Conservatory Of Music.

"I primarily treat classical musicians but I've definitely heard from some metal musicians, some quite prominent," Kretschmer wrote. "Most common issues include soreness when playing, numbness and tingling, back and neck aches, 'locking up' when attempting to execute fast passages, etc. In particular, guitarists most commonly report back, neck and wrist soreness. Some report whole arm pain, it really just depends on their jobs and the demands of what they play."

And play they will, even when injured. "As for getting a musician to stop practicing, good luck! This is one of the reasons why injuries are so often difficult to recover from." That said, Kretschmer recognizes that simply stopping playing can cause harm in a different area. "I very rarely recommend a musician simply stop playing and wait for something to heal, because not playing leads to loss of technique and weakness. Most often players require manual therapy and relative rest.... [Relative Rest] simply refers to playing less, and less intensively, than normal, while allowing the body to recover on its own. Movement and practice are important, even when injured, it's just a balance that needs to be reached in order to encourage recovery."

Naturally, like in sports, "recovery" has different connotations and expectations depending on one's perception. "I encourage musicians to think of themselves as elite athletes," Kretschmer explained. "You hear of basketball players getting injured all the time, taking 'time off' for rehab, and then returning to play. In fact, these athletes are not taking time off at all, they're doing intensive therapy tuned just right by an experienced clinician who understands the healing rates of tissues in the body, exercises and modalities that encourage healing that accelerates the timeline."

What gets tough is finding that experienced clinician. Musicians just have a different set of needs that don't fit into a one-treatment-fits-all recovery plan. Instead of the larger muscle groups frequently treated in sports medicine, their strengths lie in the small muscles. Of course, they also have a whole host of different anxiety-inducing stressors that they may not know they're fighting against, such as a subconsciously instilled perfectionism. Treatment is further complicated by how health care, particularly in this country, tends to favor those with money living in prime locales. Lastly, there's just simply not knowing what you don't know, meaning you're less likely to question a diagnosis or treatment plan if you're unprepared. "That's why I set up my website so people have somewhere to go for reasonable information in making decisions about how to deal with whatever injury they may have," Kretschmer wrote.

Along with Kretschmer, organizations like Performing Arts Medicine Association, Healthy Performers, Athletes And The Arts, and others have focused attention on musician-related health care along with advocating for preventive practices to be taught in music schools. As the CBC piece noted, this even extends to the Alexander Technique and its offshoot Body Mapping, two approaches short on research, but have their fervent believers. And, as a next step, there's a growing focus on the psychological impact of an injury on a mind trained to make music.

Healthy Performers's Jennie Morton published The Authentic Performer: Wearing A Mask And The Effect On Health in 2015, which "draws together the physiological, psychological and socio-cultural aspects of being a performer, and views them in the context of health and wellbeing." Morton features prominently in the LA Weekly piece, lamenting the "culture of silence" surrounding musician injuries. Hermann's takeaway was that musicians had a "fear of losing work," but I wonder if it's also because depression and anxiety are difficult things to talk about.

Kenny and Ackermann's study of Australian musicians, found that "seventy-five percent of the musicians showed the expected relationship between pain and depression," leading to the conclusion that "physically based treatments of performance-related musculoskeletal pain that do not address associated anxiety and depression might not prove to be effective." This mirrored what Morton told Hermann: "The people I see with so-called 'physical injuries,' there's always a huge emotional component to that. Anxiety drives muscle tension, which then makes their playing more risky. It's all intertwined. You can't really separate the two."

"It's all intertwined." That line keeps repeating in my head. Despite knowing this stuff intellectually and being hypersensitive when it comes to portrayals of depression and anxiety, I've noticed that, in my writing, I tend to treat injuries as little more than flavor text, as if they're just something that happened before or after the music. It's weird. Rereading my blurb for last year's Immortal, it's clear to me that I'm using Demonaz's injury as a framing device, similar to how Iommi's de-fingering became a foundational text for metal because those beholden to causality like me see what it presaged.

In a different light, this is a quirky side effect of the eternalism of recorded music. Unlike the player, the music they played never goes away. The player, then, always feel as though they're on the periphery of returning to whatever peak was captured on tape. But that reduces humans down to just the sounds they made, charactertures of the superficial context I can easily see.

All of this is to say that I feel like a massive dingus for checking Zero Hour's Encyclopaedia Metallum page every few months to see if the status cell flipped back to green. I didn't understand the extent of Troy Tipton's injury. He was a sound that I liked and I was impatient that sound wasn't back, like how the players on my fantasy baseball team are just number columns that I occasionally have to move to the injured list, that a few annoying clicks for me is a prolonged, grueling, potentially depressing recovery for someone else. As a fan, any injury is temporally abstract in that way, a cruel lapse in object permanence.

And yet, these injuries are hard to conceptualize for anyone outside of the sufferer. "My brother is a very strong person because I don't know what I would do if I couldn't play guitar," Jasun Tipton said to Sonic Perspectives' host Gonzalo Pozo, both taking a beat to really let that sink in. I don't know what I would do. There's just so much personal context surrounding these injuries, how could I ever know? How could I be trusted to not twist the story into something else, something that will better serve some surface-level narrative, something more recognizable to me?

It's easy to lose sight of the humanity of these musicians because they've amassed inhuman abilities that I can never fathom possessing. That they might break down is a pretty human thing, though; that one's passions might send them hurtling towards the void sooner than expected. To come out the other side is the most human thing of all. People are, naturally, curious about that. They want to know how Tony Iommi, human, lost his fingers. It kind of sucks when that's your story, when you're the accident that happened. But, thanks to a growing number of experts who are there to help, it's possible to learn to live with it. –Ian Chainey

10. Vultures Vengeance – "The Knightlore"

Location: Italy

Subgenre: heavy metal

From the first strains of "The Knightlore," you feel a jolt to the SPINE as a rush of GLORY floods the central nervous system. Senses sharpen; tired muscles come alive; something stirs in your loins. Vultures Vengeance plays epic trad the old way, the right way, the only way worth playing. Melody looms large; riffs ring true. In your mind's eye, a pitched battle rages across time and space: destriers charge and footmen fall, arrows blacken the sky, and a bloodless battle plays out in technicolor. "The Knightlore" amounts to one long cavalry charge -- into glory ride -- melodies streaming in the wind like tattered banners. Afterward comes the reflective calm: guitars untether and solos unfurl as survivors gather to mourn the fallen; daylight seeps into night as the song recedes; and the carrion birds circle above, waiting their turn. Vultures Vengeance embodies the ragged spirit of victory snatched from the jaws of defeat, summoning the stalwart sounds of heavy metal legends like Omen and Manilla Road in both riffage and subject matter. There is nothing new under the sun in metal, and there's certainly nothing new here. But what's old lives on, undying and fantastic. [From The Knightlore, out 5/10 via Gates Of Hell Records.] –Aaron Lariviere

9. Inculter – "Towards The Unknown"

Location: Fusa, Norway

Subgenre: thrash

Inculter is thoroughly Norwegian blackened thrash, which I guess we have to acknowledge as its own distinct thing now that it has evolved into its own distinct thing. A police lineup, one occurring in some alternate plane where inciting spontaneous headbanging is a crime (Utah?), would include Nekromantheon, Aura Noir, Deathhammer, Condor, and others. There's definitely a throughline connecting those usual suspects, one that's actually woven out of a few threads pulled from early thrash and speed metal, the more sanguinary NWO_HM, and, of course, the kind of Quorthonian Ratlord black metal with riffs to spare. Inculter has some of that and does right by some of that, but like its peers, it's also doing its own thing, formulating its own methodology when it comes to calculating how best to lodge its boot up your ass. If there was any concern whether Fatal Visions, the quartet's sophomore LP and first as non-teens, was worth a spin, those in the know...uh...know that my quality assessment is corroborated by the Edged Circle Productions cosign, a label that has a small discography but high hit rate. And two of the rippers present and ready for duty can claim some of that success: rhythm section Cato Bakke (bass) and Daniel Tveit (drums) also thrash it up in Reptilian (covered it) and Sepulcher (should've covered it). Anyway, yes, the thrash. Let's talk about the thrash. The thrash is good. The riffs, which are comparatively undistorted in that delightfully unmodern Kill 'Em All kind of way, are splendidly nimble, switching between lightning-quick palm-muted tremolo rhythms and untamed leads. Inculter is at its best when six-stringers Remi and Lasse Udjus tap the gas pedal, the resulting Gs pinning your head to the head rest, signaling to your brain that, oh yeah, this thing could actually turn all of us into windshield chili. In other words, it's no two-decade-late crossover Prius putterer that runs on energy derived from Anthrax's lost potential. This works the best on the one-two punch of "Final Darkness" and "Towards The Unknown," where lesser thrashers would start to rattle with speed wobbles. But, with Bakke and Tveit keep things aligned with a punky energy, the band goes supersonic, erecting the arm hairs of any metaller keen on the quicker stuff. Definite shower beer material; what future weekends will be made of. [From Fatal Visions, out now via Edged Circle Productions.] –Ian Chainey

8. Mesarthim – "Ghost Condensate I"

Location: Australia

Subgenre: atmospheric black metal

I don't recall "Trance" being listed alongside "Atmospheric Black Metal" on Mesarthim's Metal Archives page, but it's there now, right where it should be. Electronic music has played a bigger role in Mesarthim's music over time, adding a lighthearted element to the space traveling escapades of the Australian duo. You could also call Mesarthim's music "cinematic," and you wouldn't be insane to say you hear elements of power metal in there, too, or, as one Bandcamp review noted, music from the videogame Metroid Prime. This is all to say that what was once more easily boxed in along with other black metal-leaning bands obsessed with the stars above no longer fits there. The smatterings of styles and inspirations now pour over old limits, and the result is stranger, more unpredictable, and ultimately uplifting than ever. [From Ghost Condensate, out now via the band.] –Wyatt Marshall

7. Fluoride – "Deterioration"

Location: Philadelphia, PA

Subgenre: grind / hardcore

Reader, if I can write for one waffer-thin second about my personal life without inflicting too much harm, let me write this: It has been a month. This music writer, whose sole purpose is to make time for new tunes, hasn't had much time for new tunes. I know, say it ain't so. Truly dark days, darker than the last Game Of Thrones screened in a black hole wedged deep inside the b-hole of the giant space turtle that is, in fact, all the way down. Needless to say, when the opportunity has arisen and new tunes are nigh, I've been reaching for stuff I know will put my head in a vise and close the jaws until I can't feel anything anymore. So, despite the oodles of brand newness (Darkthrone, Psudoku) and out now-ness (Filtheater sounds like a legion of jackhammers reenacting Mutant League Football in a cardboard factory; it's great) that I'm manically itchy yet wholly unprepared to shoehorn into the column this month, I figured it's time to tip over the trash can that is my brain and slosh out what fluoride has liquefied. Fans (lol) of the column will recognize the name as we spotlighted this trio back in 2017. Doug actually wrote this: "Ian and I frequently joke that we could do an entire Black Market-style monthly column consisting only of DIY grindcore...." Welp...hello 2019, and hello disentanglement, fluoride's new 12-track detonation consisting only of DIY grindcore. The basics of disentanglement's sound is close to the band's self-titled how-do-you-do, but more violent and caustic, with the once-slightly skram-y blades sharpened into fine-pointed riffs. The guitars, and there's somehow only one dude playing guitar here, occasionally spill over into Discordance Axis-y strobe-light atonality, milking strident amp howls that are perverse ear candy for the slightly askew. Still, fluoride always takes a few beats to re-calibrate and simplify and punch you right in the goddamn eye, thudding thunderously with devastating slow riffs. Stuff just works. I've played this back-to-back with the too-punk-for-this-column Protocol and (1) fluoride holds its own against one of the most ruthless EPs of the year and (2) I'm like 99 percent sure I have CTE. Guitar, drums, vocals shouldn't be this heavy. And, indeed, disentanglement is heavy. I've been known to sneak in some questionable shit into this metal column, and while this kind of has shades of something I would've gone to see at a Unitarian church way back in the day, I think the blasting aural miasma will shake awake any jaded metaller. Such as myself. Especially this month. [From disentanglement, out now via Nerve Altar, React With Protest, and To Live a Lie.] –Ian Chainey

6. Vulture – "Stainless Glare"

Location: Germany

Subgenre: speed metal / thrash metal

(Prelude by Ian Chainey)

"A song titled 'Death Tone' shouldn't suck that much ass," Thanos sneered, his gloved fingers twitching. "But the B-side is rad as he-". Vultures Vengeance's protestations were cut off by the sickening snap. Just like that, Manowar turned to dust and was removed from history, along with their retro-minded metallic spawn. In their place, speed metal took root and came to rule the land, becoming the long-term foil of thrash. In this post-apocalyptic wasteland where Joe Biden was president of the Massage Therapist Association Of America, a new carrion-picker glides through the sky, seeking fresh flesh. Farewell, Vultures Vengeance. Enter: VULTURE.

(Fugue by Aaron Lariviere)

From the first strains of "Stainless Glare," you feel a jolt to the GUTS as a rush of DANGER floods the central nervous system. Senses sharpen; tired muscles come alive; something burns in the loins. Vulture plays thrashing speed metal the old way, the right way, the only way worth playing. Horror looms large; riffs ring true. In your mind's eye, a city burns while the dead riot in the streets: soldiers retreat and guillotines fall, smoke blackens the sky, and a moonlit massacre plays out in slow motion. "Stainless Glare" amounts to one long murderous rampage -- a merciless onslaught -- melodies cleaving the night like a reaper's scythe. The calm never comes: instead, guitars thrash and burn like a vagrant in a burning dumpster; dueling leads splash garish light across scenes of carnage; and the carrion birds circle above, waiting to taste spoiled flesh. Vulture embodies the madcap mayhem of Argento at his best, summoning the violent sounds of speed thrash legends like Razor and Iron Angel in both riffage and subject matter. There is nothing new under the sun in metal, and there's certainly nothing new here. But what's old lives on, unburied and fearless. [From Ghastly Waves & Battered Graves, out 6/7 via Metal Blade Records.] –Aaron Lariviere

5. Murg – "Strävan"

Location: Bergslagen, Sweden

Subgenre: black metal

We noticed all of the "Where's Murg?" posts the last two months, so here we go: here's Murg. Don't get us wrong -- we've been big Murg fans since way back, and this was always going to land here. Few bands distill icy wrath like the Swedish duo, channeling the spirit and sound of the early '90s into a modern, ferocious brand of black metal. "Strävan," the title track, is a sneering, stomping work of horror -- a swaggering tyrant of a song that flattens anything in its path. But there's more than just majestic menace, here, with bone-chilling unease closing in from all sides as the song moves on. Murg has embraced the mid-tempo march before, slowing things down to wring every last ounce of displeasure from each and every note. It's hair-raisingly effective on "Strävan," a track that comes as close to legitimately scary as anything you'll find on this column, and just another example of why Murg is one of the best black metal bands operating today. [From Stravan, out now via Nordvis.] –Wyatt Marshall

4. Sadness – "Eye Of Prima"

Location: Oak Park, Illinois

Subgenre: depressive black metal

Sadness is a hyper-prolific one-man band that moves freely between genres, pulling from atmospheric black metal, shoegaze, and expansive post-rock palettes at will. If you've spent time exploring atmospheric black metal and its various affiliates on Bandcamp, it won't come as a surprise that Sadness has found a following on the platform; this sort of lo-fi, anthemic work thrives there, but rarely does it approach the level of deeply moving, absorbing excellence seen here. "Eye Of Prima" spends the majority of its nearly nine minutes exploring a draining, troubling forward march. The painful progress, though, is broken up by, and anchored on, one of the more gorgeous choruses I've heard in some time -- a longing, bittersweet paean to someone, or something, beautiful and out of reach. [From Circle Of Veins, out now via the band.] –Wyatt Marshall

3. October Tide – "Our Famine"

Location: Sweden

Subgenre: melodic death/doom

One of my favorite parts of committed metal fandom is randomly setting aside an indefinite period of time and committing my full listening attention to a single narrow subgenre -- like dark metal perhaps, or bands that sound just like Summoning but are not actually Summoning. Recently, I dove deep to revisit one of my favorite metallic rabbitholes: the microgenre known as melodic death/doom. Unlike its heavier, less melodic cousin -- epitomized by true death/doom bands like Winter, dISEMBOWELMENT, and Krypts (see below) -- melodic death doom sets aside the gut-rending churn of atonal death metal played horrifically slow, instead focusing on gloomier but less brutal sounds. In reality, it's a fusion of mid-tempo melodeath and gothic doom. And if we're being honest, and we may as well be, the quiet bits are usually lifted wholesale from embarrassing sadboy alterna-rock, the kind that's so powerfully immune to trends that it sounds perpetually 10 years out of style no matter when you hear it -- tidally locked to lamedom. It is a testament to the power of metal that melodic death/doom somehow doesn't suck, despite itself. Everything is despondent by default; lyrics dwell on things like rain or feelings, or the feelings you have when it rains. Digging into the highlights of this scene is easy, as there aren't many bands that can actually pull this off. Katatonia are (or were) the leaders of the pack, practically inventing the style wholesale and churning out one evolutionary classic after another; a phenomenal band despite their later penchant for bad drum loops and random Tool riffs (though I love them nonetheless). Daylight Dies, one of the few American bands even attempting this sound, are responsible for a few of the genre's best riffs, least-bad clean vocals, and one of its best albums overall, the 2006 masterwork Dismantling Devotion. Which brings us to October Tide: Originally formed as a "heavy" side project of Katatonia back in the late '90s, October Tide took the early Katatonia sound to its final destination on 1997's stellar Rain Without End, also the last album to feature Jonas Renske doing death growls. Unlike some of their peers, October Tide typically sticks to harsh vocals and darker guitarwork, which helps them overcome song titles like "I, The Polluter." Fear not, friends: the riffs don't lie. [From In Splendor Below, out 5/17 via Agonia Records.] –Aaron Lariviere

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

2. Krypts – "The Reek Of Loss"

Location: Finland

Subgenre: death/doom

Imagine falling down a well, or being thrown. Your day wasn't great before that -- a few hours earlier you tried to jump a puddle and lost your feet -- of course you did -- fell hard to smack the pavement, twisting your ankle and soaking the ass of your jeans in the process. But it can always get worse. Hours later, don't ask me how you got here, you're falling 30 feet, 50 feet, more; tumbling head over heels, scraping hands, feet, knees, and face down a rough-hewn rock channel dug into the earth. As time seems to slow, you pause to reflect that the puddle must have been foreshadowing, a grim omen from a dumb novel. You smash the surface and catch a lungful of putrid water, wishing in that moment the impact was enough to snuff out your lights, but of course you're still here, still trying to breathe liquid. You sputter and squirm, trying to flail your limbs 'til you find the surface, clawing towards the air, towards freedom from this horrific turn of events. But the fall was worse than you thought. Your body isn't following your commands, not really, and consciousness slips away. Sometime later, who knows how long, you wake and crack an eyelid. Stone walls rise above, slick with slime, rising, rising to a faint pinprick of light above, and what must be moonlight. You can't feel your feet, or your arms, or much of anything besides the water and the cold. The stinking, stygian water soaking through the collar of your shirt; the cold soaking into your bones. The water can't be very deep, you surmise, to leave you broken but breathing at the bottom of the shaft, tangled up like a broken kite. You should be frantic, but the numbness in your limbs is pervasive; it does something to your head, and you feel a bit fuzzy is all. As you lay there, staring up at that dim, distant glimmer of light -- knowing where this is going, trying not to think about it -- you hear something in the back of your head. A chiming guitar, dreary and comforting. It's all in your head, like a ringing in the ears; not actually real real, but real enough. It sounds like a song, an ugly one, but you'll take it. At least you're not alone down here. [From Cadaver Circulation, out 5/31 via Dark Descent Records.] –Aaron Lariviere

1. Remete – "Stillness"

Location: New South Wales, Australia

Subgenre: atmospheric black metal

Following Woods Of Desolation's 2014 landmark atmospheric black metal album As The Stars, mastermind D, the man responsible for all the heartrending, sky-splitting riffs, disappeared. The sustained silence following As The Stars was something of a cliffhanger. Woods Of Desolation had been around for some time, but As The Stars reached a new level of critical and, in our small world, popular acclaim. A follow-up was eagerly awaited, and we're still waiting. But at the very end of 2017, D returned with two new projects -- Remete and Unfelled -- and a revival of his incredible muscular atmospheric black metal project Forest Mysticism. All are excellent, but D has outdone himself with Into Endless Night, Remete's debut full-length. I can't stress enough that you should seek out this album in full (link below), but "Cold Within," the opener, will get the message across. Pained, gorgeous melodies collide with infectious, full-throttle, and raging blasts, here, while surreal instrumental passages achieve bliss. Everything here is deeper -- the vocals are absolutely ferocious but unusually expressive, the guitarwork inundating, by turns invigorating and even tender. Give it a listen -- it opens up one of the best albums of the year. [From Into Endless Night, out now via the band.] –Wyatt Marshall