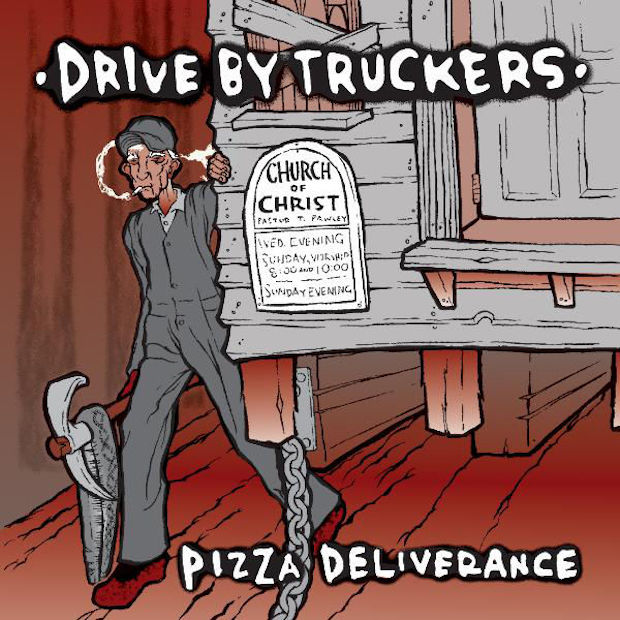

Released 20 years ago tomorrow, on May 11, 1999, Pizza Deliverance is the second album by the Drive-By Truckers, but it's actually more like a debut. The Athens, GA band -- boasting at the time a loose lineup of whoever showed up to crowds, insisting that rehearsals were a waste of time, and playing to larger and larger audiences -- had been working on these 14 songs since their first notes together. In fact, they'd even used two of these songs -- "Bulldozers & Dirt" and "Nine Bullets" -- on their debut 7" single, which they self-released in 1996 when almost no one was releasing vinyl. But when it came time to actually record a full album in 1998, they enjoyed a weird burst of creativity, wrote a bunch of new tunes, and collected those on their actual debut, Gangstabilly. And it's not hard to see why they would be excited to be recording "The Living Bubba" and "Panties In Your Purse" and "18 Wheels Of Love," all of which remain staples in their live sets two decades later.

By 1999, Patterson Hood, Mike Cooley, and Rob Malone had started working on what have become known as the "Heathens" songs, which constitute one of the most ambitious undertakings in Southern literature at the end of the century. They wrote about people and places that weren't typically mentioned in novels or rock lyrics: unreformed rednecks, country crime lords and the yokel henchmen they hired, people like Sheriff Buford Pusser of Walking Tall fame, people like Ronnie Van Zant of Lynyrd Skynyrd and the racist governor of Alabama, George Wallace. They were portrayed with all their contradictions intact, as the band depicted the South as a place of both pride and shame. Subsequent albums, especially 2001's Southern Rock Opera and 2004's The Dirty South, would play like collections of prickly short stories, funny and sad and sometimes inscrutable: the bedrock of the band's catalog and legacy.

Pizza Deliverance became a clearinghouse for older songs that didn't quite fit this new mode of songwriting, a means of closing out one chapter so they could push ahead with this new one. They had to leave much behind to move forward. Part of what they left behind: the country kitsch humor, derived from the likes of Mojo Nixon in the late 1980s as well as alt-country upstarts like Southern Culture On The Skids and BR549 (who notoriously rewrote The Andy Griffith Show as something akin to a Hieronymus Bosch painting). As those album titles and even that band name suggest, the Truckers weren't especially cautious about playing up some of the kitschier aspects of southern culture. What's amazing, however, is the degree to which these early songs -- and especially the ones on Pizza Deliverance -- complicate that impression by taking their subjects very seriously and rendering their characters with a compassion that can be disarming.

Take "Bulldozers & Dirt," the very first Truckers song. Accompanied primarily by a mandolin that sounds like it's been restrung with rusty barbed wire, Hood sings about a man who marries a woman he tried to rob, then falls under the spell of her teenage daughter. To distract himself, he drives a bulldozer around in their backyard, relocating piles of red clay and dirt over and over and over. "I've lived with your mama for 11 years, through good times and bad times, fistfights and tears" Hood sings. "But something comes over me when you come near, so won't you come over and sip on this beer." As the first-person pronouns suggest, he's singing from that man's conflicted point of view, and there's not a lick of condescension in the song or anything else that suggests a punchline.

The Truckers at this stage in their career were best when they were subverting Southern kitsch tropes. One of Hood's best songs is "Margo And Harold," about two Southern oddballs who ought to come off as objects of humor. And they do, of course, but Hood's too fine an observer of details to make them merely objects of derision: "Midlife crises, high on Dilaudid, Valium, and crystal meth/ Harold and Margo, feeling no pain/ Fifty and crazy, big hair and cocaine." Ultimately he's intensely scared of this outrageous couple, but also he admires their recklessness, their headlong approach to life.

The surprise of Pizza Deliverance, however, is Cooley, who emerges as an equally deft songwriter. An inventive and mischievous lead guitarist who can triangulate Crazy Horse, Sonic Youth, and the Buckaroos, he didn't start writing songs until the mid 1990s, following the breakup of his and Hood's previous band, Adam's House Cat. "I started writing songs the way everybody starts writing songs -- by taking personal experiences," he told me recently. "It started out as a therapeutic thing, because I was in such a dark, sad place. I was trying to get stuff out of my system, and it felt pretty good."

He had only one song on Gangstabilly, a startlingly empathic ode to a divorcee called "Panties In Your Purse," but Pizza Deliverance proves that was no fluke. It's the first time he shows he can keep up with Hood, then as now a prolific songwriter. "Uncle Frank" ought to buckle under the weight of its concept, but Cooley relates the history of north Alabama from the perspective of a man displaced by progress: The construction of Wilson Dam might have supplied electricity to the region's hollers and hills (and even powered historic sessions at FAME and Muscle Shoals Sound Studio), but it displaced people like Uncle Frank, a man who "never had a job or needed one in his life." Those final lines sketch out a dark fate for the character, as Cooley's economical lyrics beautifully understate the tragedy. It's one of the finest moments in their catalog.

Not every song holds up quite so well. "Zoloft" is a one-listen novelty, and "The President's Penis Is Missing" was already dated political commentary even in 1999. And then there's "Nine Bullets," written during a time when Hood was suicidal (i.e. his late 20s) and fantasizing about offing himself and those around him. He tries to leaven the grim subject matter with some odd humor about missing socks, but it's still a song about planning a mass shooting. Especially after "Guns Of Umpqua" off 2016's American Band -- a song about a school shooting victim that stops time for a few beautiful, sad moments -- "Nine Bullets" sounds weirdly flippant in hindsight. Maybe that's meant to defuse the situation, to suggest that the narrator never had the intention of enacting his plan, but it remains oddly off-putting on an album defined by its creators' empathy and compassion.

Pizza Deliverance ends with "The Night G.G. Allin Came To Town," which ought to be a joke song but ends up being so much more. Less about the notorious shock rocker's only Memphis performance and more about the reactions to all the thrown feces, it looms large in Trucker lore. I've heard people say that it was a peace offering, that Hood wrote it to mend his relationship with Cooley, that he was trying to persuade his old friend to join the Truckers. Both of them dismiss any notion of a falling out between them. "I wrote 'G.G. Allin' as a birthday present to him," says Hood, "because I knew it would make him laugh. Every line of that song is just spot on a moment in time from our lives when we were so down and out and laughing hysterically."

In the song the two friends are sitting in a booth at a diner in Memphis, hungover and piss broke, sipping coffee and eating hash browns and listening to the couple in the next booth discuss Allin's show the previous week. "Honey, I don’t believe this ... It says he took a shit on the stage and threw it into the crowd. But he was gone before the cops could come and shut him down." Even today I wait for the punchline, and it's a good one: Allin was "gone before the shit came down." And then there's another: "Punk rockers paid $12 to be shit on!"

But then the song keeps going, and Hood narrows the focus until it's just him and Cooley -- the two mainstays in the Truckers, the only two members who played on Pizza Deliverance and who are still in the band. They've never shied away from singing about their rock idols (see: "The Living Bubba," "Carl Perkins' Cadillac"), but this is less about living up to someone else's standards and more about living up to your own. It's a song about how not to be a rock band, although I've never been able to pinpoint the song's exact moral. Maybe it's: Don't do it just for spectacle. Or: Don't shit on your fans. Or maybe it's something only the two of them understand, a secret joke among them. Whatever the case, they've been heeding that lesson now for 20 years.