"You're too old. Let go. It's over. Nobody listens to techno."

That was Eminem in 2002, giving some sincere and heartfelt advice to Moby. Like a whole lot of the things Eminem said when he was at the peak of his fame, it hasn't aged all that well. (Another thing that hasn't aged well: Eminem lobbing a homophobic slur at Moby on that same song.) Factually, Eminem was right, at least about techno. Very few people in 2002 were listening to techno, the dizzy and breakbeat-driven dance music variant where Moby first made his name. Techno, and the underground rave scene that produced it, had more or less been legislated out of existence, the casualty of a new wave of parental drug panic. But Moby wasn't making techno anymore. And everyone was listening to Moby -- or at least hearing him, whether they wanted to or not.

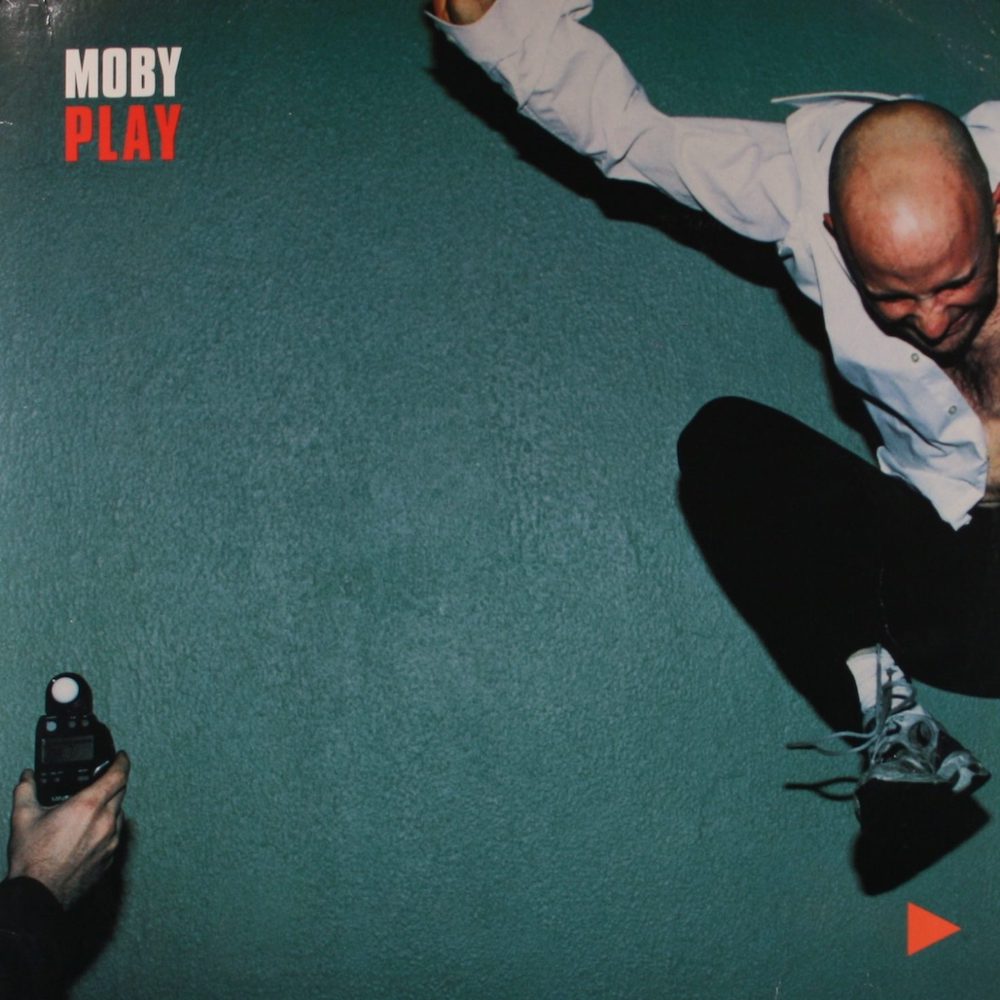

Moby's Play, which turns 20 today, has now sold about 12 million copies worldwide. Those are mind-boggling numbers to anyone who is not Eminem, and yet they don't even tell half the story of Play. The real story of Play is how the album made its slow bleed into popular culture. Within a few years of the album's release, Moby had licensed every one of the album's 17 tracks to advertisers, or movies, or TV shows, or some combination of those three. Even if Play hadn't become the circa-2000 soundtrack for every last slightly-hip-office-worker dinner party, the Y2K equivalent of High Violet or some shit, it still would've become an inescapable ambient thrum. It was the album that you couldn't escape if you tried, the transactional backbeat of the first dot-com boom. It sounded like capitalism.

This was an unlikely turn of events. Moby had already had a long and strange career before he put together Play. After playing in teenage Connecticut hardcore bands and playing rap records in New York nightclubs, Moby had found himself drawn to the rave world. He started making techno tracks, tracks that fused frantic abandon with starry-eyed melodic sensibilities. Moby was canny, and a trick like the sample of the Twin Peaks theme on 1990's "Go" was enough to make the song into the pre-internet equivalent of a viral hit. He also knew that the underground rave scene, a world of faceless producers with interchangeable alter-egos, was begging for a big-tent star, and he became that. He was an outsider weirdo with an irresistible-to-writers backstory: He's a Christian libertarian who makes bacchanalian dance music! And he's a vegan, whatever that is! Critics fell all over Everything Is Wrong, the 1995 album that swung from frothing house to tantrumy hardcore punk to ethereal neoclassical. But Moby threw away all his goodwill on Animal Rights, a turgid alt-rock album that nobody much liked. When he made Play, he was thinking about quitting music and going to school for architecture.

Play itself had its own weird genesis. A writer friend gave Moby his copy of Sounds Of The South, a box set of ancient field-recorded folk and blues songs that the musicologist Alan Lomax had collected. Moby sampled a few of those songs, using the voices of these long-gone poor black performers and building glassy, loping electronic dance tracks out of them. Those tracks don't make up all of Play. There's also some head-blown synthpop, a bunch of downtempo murmurings, and a noisy experiment in late-'80s industrial. But if Play has a soul, it's in those old samples. (And maybe it's also in the sample of early-'80s rap originators Treacherous Three, folk musicians in their own right, on Play's big-beat jam "Bodyrock.") In his time, Moby had been considered a futurist, and yet here he was, digging into these mythic and ancestral American sounds.

Maybe those old blues samples were a gimmick, or at least an aesthetic hook. But they worked. Critics loved Play to pieces. They read things into those old samples. Depending on who you asked, Moby was a new kind of folklorist, reframing the ghosts of our cultural past through the sounds of the day. Or he was a trickster, refashioning forgotten detritus into dancefloor gold. Or he was an opportunistic plunderer, a white man capitalizing on the labor of these forgotten black musicians.

All of those readings made their own kind of sense, and none of them really got at how the album sounded. Play was pretty. It felt like ideal background music, music to zone out to when you were working or studying or staring blankly out your window. Moby might've been drawing old sounds, but he was also pioneering a new one: Upwardly mobile muzak. You could feel cool for liking the stuff on Play. You could feel confident that nobody would clown you for playing what was essentially a moodier Fatboy Slim record. You could jam "Porcelain" in a car and feel like you were in a Miramax movie. The music swung smartly between genres and textures and vocal tones, but it never demanded too much of you. It always rolled out pleasantly, lending its easy sheen to whatever else might've been happening.

In a way, licensors and advertising firms and soundtrack coordinators understood Play better than critics did. (They might've also understood it better than Moby, who spent the shows on his endless Play tour busily pinging around stages, grabbing turntables and guitars and bongos, acting like some kind of neo-punk messiah. Those shows were fun, but they were almost comically distant from the chilled-out money-spending music that Moby was making.) Even more than the Massive Attack or Sneaker Pimps tracks that had been soundtrack-bait in the years before Play, Moby's music would bubble unobtrusively under car chases or sex scenes or coffee commercials, making cynical mass-market storytelling appear slick and of-the-moment.

This was nothing new for Moby, who, two years before Play, had released the film-music collection I Like To Score. (Such a cut-up, that guy.) And yet Play kicked that tendency into anther gear, dumbing down its tempos to double its dollars. And slowly but suddenly, it was everywhere. By the time Eminem let loose on Moby, the entire American populace had been quietly pickled in Play for years.

Play was comfort food. Because of those old samples, Play -- like the O Brother, Where Are Thou? soundtrack, another massive left field hit from the same year that also borrowed songs from the Alan Lomax archive -- touched some collective note of ancestral longing in an age when it seemed like technology had taken over everything. (If only we knew!) But because of its synthetic textures, Play also made use of that same technology, and it never sounded anachronistic. The album never pushed. Instead, it gently nudged us into our present.

Before Play, artists tended to be embarrassed about the very idea of licensing songs to commercials. It just seemed like a lame thing to do. Moby, who was already lame, had nothing to lose. And so Play marked some inflection point, a moment of rupture where we all decided to rethink the ethics of licensing. In the years that followed, indie bands would consider it a win if Volkswagen wanted to use a piece of a song. It lost all its stigma, and Moby was the entire reason for that. He rewrote the rule book. He did it at the right moment, too. Play came out at the beginning of the Napster revolution, the moment just before young people generally lost all interest in paying money for music. For all we know, Napster is the way so many of those ad execs and soundtrack coordinators heard Play in the first place. And suddenly, Moby's success looked like a roadmap for survival in an uncertain time.

Play did what it did in new ways. "South Side" eventually became a hit once Gwen Stefani jumped on it, but that was a case of radio programmers playing catchup. The album was a hit that wasn't driven by hits. Instead, Play bloomed through the slow seepage of all those syncs. And the success was really something. Play made Moby famous. For a brief moment, he was a superstar, able to put together a touring summer festival and book David Bowie and OutKast and Incubus to play under his banner. Moby moved in new circles -- the sorts of circles where you can rub your dick on Donald Trump or hook up with indie-film darling Christina Ricci (so big ups if you bought his CD). That success didn't really last, but Moby will presumably be rich for life off of Play and what it wrought.

Twenty years later, the chief legacy of Play isn't exactly musical. It's in all that ad money that recalibrated the music economy. And it's in the very notion of chillout music. Downtempo electronic music existed before Play; Moby made plenty of it himself. But before Play, the chillout thing was a vague offshoot of rave culture -- the tent where you'd go when the drugs were starting to wear off. But 20 years after Play, chillout is a branded playlist that seeps in over office speakers, designed to keep your productivity up while creating a pleasing open-flow work environment. It's algorithmically derived background nothingness. It's the sound of coding, of clickety-clack laptop busywork, of your youth wasting away.

We're all too old. Let go. It's over. RIP to techno.