In case you missed it, the Red Hot Chili Peppers love California. It is, in fact, so hard-wired into their identity that, if you were so inclined, you could release a parody track called "Abracadabralifornia" and people might even mistake it for the real thing. They have often made their sound, themes, and identity synonymous with at least one interpretation of their state of origin. You know this about the Red Hot Chili Peppers. And people already knew this about the Red Hot Chili Peppers when they named an album Californication, of all things, and sent it out into the world 20 years ago tomorrow.

For many young people around the country, the Red Hot Chili Peppers were a gateway band -- a popular group through the '90s alt-rock boom from whom you could trace the paths back to different progenitors than those of their peers. (Plenty '90s rock acts could point you to Hendrix, but RHCP could also point you to Parliament.) And as such, they were also the first impression of a lot of things for those young listeners, whether you were a teenager when Mother's Milk came out or whether you were of the next generation, RHCP one part of your introduction by way of their massively successful late '90s singles.

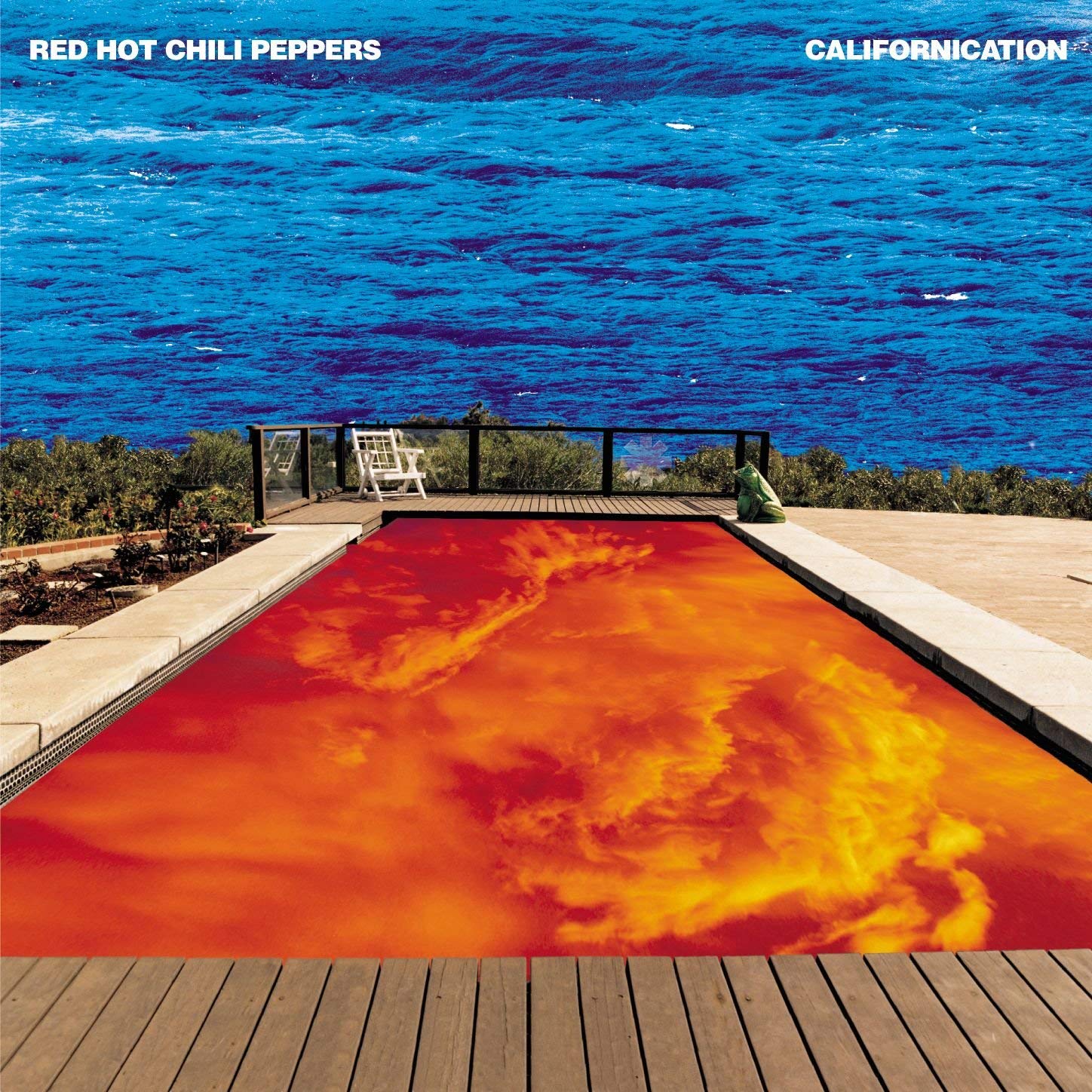

If you were part of the latter group, Californication might live on as their definitive work, rivaled only by their 1991 breakthrough Blood Sugar Sex Magik. This, in some ways, was the album that seemed to capture everything this band was always supposed to be. It made them feel, at the time and aided by a clutch of singles destined to soon be ubiquitous in every small town shopping mall and on every small town alt-rock station, as the embodiment of a certain kind of late '90s iconography. Extreme sports and artificial energy drinks and turn of the millennium graphic fonts attendant to both. The same sun-drenched place glimpsed in '90s alt-rock videos, where everything seemed more saturated than it could possibly look in real life.

It didn't matter if this was authentic or the stuff of skateboard video games and sunglasses stores. This was yet another small chapter in America's long history of mythologizing California, the Golden Coast and the frontier and the full realization of this country's identity. The Peppers, for better or for worse, felt like the total fulfillment of that promise, a vaguely cartoonish one for the end of a century.

"Californication," the song, despite being named with a very characteristically RHCP pun, was actually about the darker side of things. You see that name, and you'd immediately assume it was another piece of ribald funk with Anthony Kiedis offering up a semi-juvenile rap. Instead, it's a fairly mournful, balladic composition. There are still some clunkier lines, naturally, but there are also some truly poignant ones. Rather than a celebration of their hometown and its mythology, "Californication" echoed the addiction, alienation, and self-destruction that had actually colored the individual lives of the Chili Peppers' members.

The song touched on another trope, of the young person lured in from somewhere in the middle of the country, drawn to one of the urban centers sitting at America's polarities, only to be eaten alive upon arrival. It was not Kiedis straining out the name of his favorite state, as in the chorus of "Dani California" seven years later, searching for drama by letting that West Coast iconography fill in the blanks. It actually, truly, sounds pretty sad when he sings "Dream of Californication."

Californication, the album, is not exactly "dark." But it is more consistently gentle and somber than they had ever been before.At this point, this band, and its individual members, had been through it. And you could hear that in the music. Californication represented apreviously hard-to-imagine prospect: an older, ever so slightly wiser Red Hot Chili Peppers.

The Chili Peppers had already come back from horrible circumstances. They had already lost one guitarist and friend to drug addiction, when Hillel Slovak overdosed in 1988. It compelled Kiedis -- whose tumultuous upbringing and relationship with substances would be further detailed in his 2004 memoir Scar Tissue, named for one of Californication's key tracks -- to get clean. His struggle would continue on through the '90s, with one relapse casting a shadow over 1995's already-troubled One Hot Minute. After Slovak's death, they'd hired a kid named John Frusciante, and the band went on to release albums that started to gain wider and wider traction, initially peaking with Blood Sugar Sex Magik. The explosion of fame proved a lot to process, and Frusciante departed the band and subsequently battled a brutal heroin and cocaine addiction through the middle of the decade.

The ensuing years were not easy for the rest of RHCP either. Aside from Kiedis' personal struggles, the prospect of following Blood Sugar Sex Magik was challenging, especially as they tried to find a groove with their new guitarist, Dave Navarro. The chemistry never quite developed, and despite having some strange, enduring RHCP tunes, One Hot Minute was regarded as a disappointment by every metric -- the hits weren't big, it didn't sell as well, neither critics nor fans embraced it. Navarro would leave the band, and Flea convinced Frusciante to rejoin the fold.

It was a strange place to be. RHCP had already been around since the early days of the '80s, but they were now approaching the other side of another decade, one that had granted them stardom. They had already undergone runaway popularity, the valleys that can follow; they had already undergone addiction and recovery and loss in multiple cycles. The only album they had released since their breakthrough had been written off as a failure. And so, going into the late '90s, they had rebuilt what in hindsight can easily be called the definitive Chili Peppers lineup -- Kiedis, Flea, Frusciante, and Chad Smith. And they were positioned for, in need of, a comeback moment. They got one.

Whether it was the travails of life or having Frusciante back, RHCP returned with an album that broke new ground for them artistically. Softer, more introspective, more tasteful. Kiedis, suddenly, could really, really sing when he wanted to. (There're plenty of annoying honks across the album still, but there’s also singing.) It was a rebirth for the band creatively, personally, and narratively. Californication became a huge success, surpassing the heights of its predecessors and unleashing a series of singles that became some of the band's pivotal tracks.

Along with the aforementioned title track and "Scar Tissue," Californication also featured "Otherside" -- a genuinely pretty and cathartic composition that ranks amongst the band's very best. It's hard not to hear the reintroduction of Frusciante as being crucial to songs like these. In his second run with RHCP, there was always something odd about seeing him onstage. He seemed sadder and weirder than the rest of the band, or at least than the music they made. And that in turn pushed RHCP in this era, Frusciante's guitar work effortlessly shifting between clean and fluid, then percussively funky and precise, classicist then wildly creative. Say what you will about the resulting sounds they made collectively, but RHCP could always boast a small collection of musicians who played off each other perfectly. Frusciante was vey much a part of that, his guitars adding just the right textures to the rhythms of Flea and Smith, his background keens lacing Kiedis' melodies with melancholy.

There were still remnants of the old Chili Peppers, especially in the sex funk of "Get On Top" and "I Like Dirt" and "Purple Stain." "Around The World" felt like a next step from the funk-rock of their past, not a retread nor repudiation, almost summing up the band's extremes: the tightly wound verses giving way to a soft-alt-rock chorus, Kiedis rapping then showing off those new hooks he could deliver. And then, still ... scatting towards the end of the song.

All of which is to say that, the more mature iteration of RHCP some of us saw in this stretch of their career wasn't ever 100% true, nor was the aging/soft version decried by those who missed the partying goofball pranksters of the past. If you still wanted RHCP to be fun and silly and puerile, there was a bit of that on Californication. If you had been curious what would happen if earlier, mellower tracks like "Under The Bridge" and "Breaking The Girl" had not been outliers, you got your answer on Californication. Across its 15 tracks, the album had a whole lot of room for all the moods and sounds this band wanted.

And oftentimes, those explorations, those sounds of a just-about-middle-aged Red Hot Chili Peppers, resulted in some of their best songs, including but also beyond those major singles. "Parallel Universe" remains one of their nimblest and most propulsive rock songs. Working off an inverted structure, "Savior" flipped between thunderous verses and dreamlike, wispy choruses (or chorus stand-ins).

Frusciante's guitar work was once more notable in "This Velvet Glove," crystalline pinpricks and acoustic strums functioning like steadily intensifying rainfall in the verse before whipping sheets of water around in the chorus. Fans gravitated towards closer "Road Trippin'" as a quiet and matter-of-fact tribute to friendship, especially the longterm kind the band possessed, the kind that weathered awful ups-and-downs.

It was fitting that Californication concluded with a tribute to journeys taken together, to the endurance of close bonds amidst trials and defeats. After their respective battles through the middle of the '90s, Californication was the sound of four guys coming back together, still with some unspoken musical connection between them in their bloodstreams, and revitalizing each other. They crafted themselves a turning point.

From here, their magnitude was confirmed. Rather than continuing a potential decline set off by One Hot Minute, Californication redirected the path upward, to sustained status as one of the world's last gigantic rock bands, to Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame inductions, to a striking amount of albums sold.

But more important than material metrics, Californication remains one of the prime arguments in a messy, surprisingly convoluted career if you are going to try and make your case for the Red Hot Chili Peppers. As popular as this band has been and will remain, debates will never go away regarding their actual quality. There is certainly a lot of embarrassing output to their name, and they're being one of those bands you can get into easily at 13 years old always seems to saddle them with a guilty pleasure status as you get older.

But some interesting things happened with Californication and the albums that followed through the next 10 years, during Frusciante's second stint. Californication, By The Way, even Stadium Arcadium -- these albums have the same genre collision the band had always toyed with, but there's a lot of other stuff crashing together, too. Good ideas and bad ideas; prodigious musicality and amateurish lyrics; moments of actual beauty and gravity mixed with high school level come-ons.

Chances are none of that was on the mind of kids who found this album in 1999, though. They weren't on mine, at least. At the time, it was the sound of these four guys reunited, at the height of their powers, not without missteps but able to evoke some fantasy place somewhere else. Later, you could decipher the darkness hanging at the edges, too. But for a while, the Red Hot Chili Peppers offered music that sounded like a transmission from the West Coast that was just as glamorous as more respectable Californian legends. Whatever you think of this band, that world they created resonated for a lot of young people then. And because of that, there's something about Californication that still resonates today.