There are a million theories as to when exactly punk was born. Some say it was the moment when Richard Hell first used a safety pin to hold his tattered clothes together; others pinpoint it to the release of the Damned's epochal 1976 single "New Rose." But for Mike Watt, it was somewhere between minute eight and minute 11 of Peter Frampton's "Do You Feel Like We Do." As the Minutemen/fIREHOSE bassmaster once quipped: "Peter Frampton sang, 'Do you feel like I do?' No, I don't. You're wearing a kimono!"

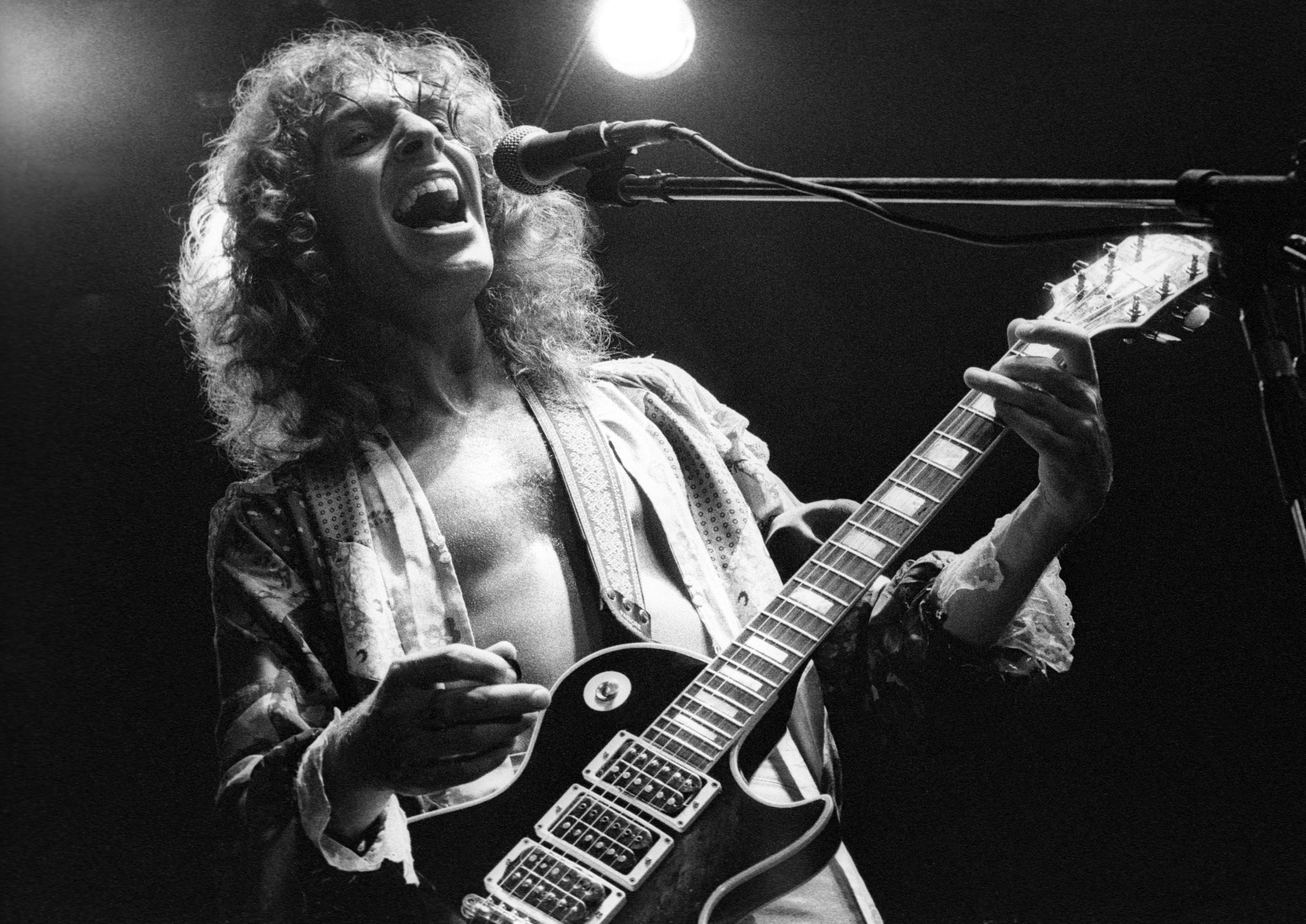

Originally appearing on Frampton's 1973 sophomore effort, Frampton's Camel, "Do You Feel Like We Do" is better known today as the final track on side four of the 1976 double-album concert document Frampton Comes Alive!, where it gets stretched out to twice its original length. And depending on your age and tolerance for fretboard theatrics, the song either represents a model of '70s rock in excelsis, or a not-so-crash-course in Why Punk Needed To Happen. The live version runs nearly 14 minutes, during which Frampton puts on an arena-rock clinic using every trick in the playbook: jazzy Santana-esque mysticism; raunchy, Zep-heavy grooves; a fist-pump chorus; a guitar solo; an extended acid-funk breakdown; a spotlight turn from Bob Mayo on the keyboards; another guitar solo; a call-and-response section where Frampton asks the crowd several times whether they are all indeed feeling like he does. And then: the coup de grâce that would forever become the very first thing you think of when you hear the name "Peter Frampton" — the talk box solo.

Thanks in large part to that saliva-soaked gimmick, Frampton Comes Alive! transformed this unheralded singer/songwriter into a new kind of guitar hero for a new generation, at a time when hard rock was starting to outgrow its blues roots and acquire more of a pop polish. Upon the album's release, Frampton was already 10 years into his career, having fronted '60s British Invasion hopefuls the Herd in his teens, before joining blooze-rockers Humble Pie and providing some six-string assistance on George Harrison's post-Beatle opus All Things Must Pass. Despite those impressive credentials, Frampton's initial solo efforts failed to connect with a mass audience in the early '70s, perhaps because it was unclear if he was trying to be a heavy-duty, jam-happy rocker or a sensitive cosmic folkie. But by 1975's Frampton, he found a comfort zone somewhere in the middle, earning him his first Top 40 album in the US and enough clout to start headlining theaters.

Frampton had quit Humble Pie in 1971, just before they broke out with the release of their legendary live set Performance: Rockin' The Fillmore. ("I felt as if I had made the worst decision of my career," he said.) Seeing his former bandmates soar to success while his own solo career crept along at a more incremental pace, Frampton decided to replicate the formula, releasing a live album that would double as a career overview to bring his new fans up to speed. Of course, we now know the gambit worked — though like everything in Frampton's career up to that point, it was a slow and steady climb to the top.

When it hit stores in January 1976, Frampton Comes Alive! debuted in the lower depths of the Billboard charts at 191. But regional radio airplay and word-of-mouth gradually coalesced into nationwide exposure, and in April, the album hit #1 and stayed there for the next 10 weeks. While the garbage-strewn streets of London were paving the way for punk, Frampton Comes Alive! chased away the black clouds hovering over a post-Watergate America. Racking up sales of over eight million in the US, it became the official feel-good soundtrack to basement rec-room parties, backseat makeout sessions, and Friday night open-window aimless drives. (As noted rock scholar Wayne Campbell once observed: "Everybody in the world has Frampton Comes Alive! If you lived in the suburbs you were issued it. It came in the mail with samples of Tide.") The album swiftly transformed this consummate musician's musician into the biggest pop star in the land, a veritable Leif Garrett with a Les Paul. To understand the sheer magnitude of this shift, just imagine, say, Kurt Vile suddenly becoming as popular as BTS.

There's no single magic-bullet theory as to why Frampton Comes Alive! blew up the way it did. Certainly, its release was perfectly timed to capitalize on the surging appetite for live albums in the mid-'70s, following a trail blazed by the Allman Brothers Band's At Fillmore East, Deep Purple's Made In Japan, and KISS Alive! Back in the '60s, live sets tended to take the form of crudely rendered cash grabs, but in the '70s they came to symbolize something greater. In an era where your interaction with an artist was mostly limited to staring at their record cover for hours on end, live albums functioned as a primitive form of social media — a forum for not only experiencing their music in a more naturalistic setting, but also a medium through which the posters on your walls came to life. For many fans, a live record was where you could actually hear a favorite singer's speaking voice for the first time, making the stage banter as iconic as the songs they introduced. (Inevitably, their importance has diminished as artists have become more accessible in the digital age, and a simple well-timed YouTube clip can do all the heavy career lifting a double-vinyl set once did.)

But while Frampton Comes Alive! bears all the hallmarks of what we now call arena rock, it's not technically an arena-rock album. Like many of the legendary live records of the period — like the Who's Live At Leeds — it's really a small-theater-rock album, capturing an artist at the crucial turning point where years of playing clubs have translated into bigger bookings, but there's still an adrenalized intensity to the performance that has yet to calcify into clockwork arena-act proficiency. Captured primarily at San Francisco's Winterland Ballroom (and supplemented with recordings from shows in Long Island and Plattsburgh, NY), the magic of Frampton Comes Alive! is that it sounds like Frampton is performing for a crowd 10 times its actual size.

More than just provide an anonymous roar between songs, the audience heard on Frampton Comes Alive! practically deserves mechanical royalties. You'd be hard-pressed to find fans more enthusiastic than the ones watching Peter Frampton play in 1975 before he became world-famous, and many of the record's enduring charms can be chalked up to them — like the way their handclaps perfectly lock into the funky sway of "Doobie Wah" as if they were an auxiliary percussion section, or how they hang onto every chord change in the solo acoustic instrumental "Penny For Your Thoughts" like parents excitedly watching their kid perform at a school recital. And where a live album is supposed to make you feel like you were at the show, the truly special ones remind you that being at the show isn't the same thing as knowing exactly what's happening onstage. When you hear the crowd mysteriously erupt during the "Do You Feel Like We Do" breakdown for no apparent reason, it's the audio equivalent of craning your neck around the tall guy standing in front of you — and it's only when you hear Frampton start squealing through his talk box that you understand what all the fuss was about.

For the millions of people who experienced Peter Frampton for the first time through Frampton Comes Alive!, hearing those rapturous crowd reactions made you want to be part of what sounded like the happiest cult on the planet. And the exuberance of those fans seems to have a noticeably humbling effect on Frampton himself. For all the fretboard wizardry and talk-box showboating heard on Frampton Comes Alive!, the album's greatest special effect is Frampton's own natural voice, which betrays an unvarnished, vulnerable quality you just don't hear in his overly mannered studio recordings. (For instance, while the live version of "Lines On My Face" retains the dazed, nocturnal quality of the original, Frampton's subtle changes in vocal inflection and emphasis on the chorus deepens the song's emotional impact exponentially.) And what really stands out when you hear the album today is how much the songs read like a diary of Frampton's own becoming — when he sings the line, "I wonder if I'm dreaming/ I feel so unashamed/ I can't believe this is happening to me" on "Show Me The Way," the lyric's original romantic intent is recast as an awestruck realization that his years of hard work were finally paying off.

That song and the equally sentimental serenade "Baby I Love Your Way," have kept Frampton in regular oldies-radio rotation for the past four decades. But their enduring popularity above all else in his canon has created a one-dimensional image of Frampton as a '70s soft-rock novelty. As a result, Frampton Comes Alive! has come to be seen as a fleeting commercial phenomenon more than a serious musical statement. It's rarely mentioned in the same breath as Rumors or "Led Zeppelin IV" or other era-defining rock classics, and is routinely shut out of Best Albums Of The '70s lists put out by major publications. Growing up in the '80s, you never saw Peter Frampton shirts at the head shops alongside the regulation Stones and Floyd tees. For years, Frampton was something of a pop-cultural punching bag, subjected to desecrating Dinosaur Jr. covers and an appearance on the Reality Bites soundtrack that mostly served to underscore what a square Ben Stiller's character was. And to date, Frampton's never been the beneficiary of an indie-hipster reclamation effort, like what Vampire Weekend did for Graceland or, more recently, Bon Iver for Bruce Hornsby.

For many, Frampton Comes Alive! is an artifact frozen in time, a shorthand signifier of '70s-rock excess like "more cowbell!" and "FREE BIRD!" However, much of this reputation has little to actually do with the album itself, which, in its absorption of myriad '70s styles, stands today as the singular missing link between proto-metal and yacht rock. Rather, the album's legacy has been unfairly tarnished by what came immediately after.

It's fitting that the gatefold vinyl version of Frampton Comes Alive! doesn't open up like a regular double album; it unfolds downward like a reverse-centerfold, with Frampton's golden-godly face taking up most of the front cover, and the rest of his body below the fold, his hands playing his guitar. Alas, that would prove to be an all too fitting metaphor for an artist who, following his long-gestating career breakthrough, got swiftly sucked into a star-making machine that valued his visage over his musicianship, and tried to turn him into something he wasn't.

Frampton's first post-success release, 1977's I'm In You, reintroduced him as a bare-chested boudoir balladeer. While he was able to move a couple million copies on hype alone, his rocker reputation took a serious hit; a starring role in 1978's critically savaged Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band movie pretty much killed it completely. (To add injury to insult, Frampton was nearly killed in a car accident in the Bahamas that year.) And despite trying to stay current by dabbling in new wave, by the early '80s, Frampton's albums were barely denting the Top 200. While Frampton is synonymous with the '70s, there was something very 21st-century about his rollercoaster career trajectory. Frampton was essentially a viral success before the term existed — and then he basically got milkshake-ducked for the crime of wearing a buttonless blouse and shiny pink pants.

But if Frampton's story stands as a cautionary tale of how quickly fame can turn into infamy, his career since the '80s has anticipated another 21st-century reality: the need for musicians to take control of their brands and nurture their limited but loyal fanbases in creative ways. In 1987, Frampton was invited by his old school chum David Bowie to play on Never Let Me Down and the subsequent Glass Spider Tour — a moment that's often seen as a nadir for Bowie, but given Frampton's fortunes at the time, it was a much-needed shot in the arm. Since then, he's sporadically released new music at his own casual pace, putting pursuit of his passions — be it a Grammy-winning collection of stylistically eclectic instrumentals or the all-blues covers set he's putting out this week — over chasing the charts. (His talk-boxed rendition of Soundgarden's "Black Hole Sun" now sounds especially poignant in light of Chris Cornell's passing, as if the song was being channeled through an apparition.) And in the gaps between records, he's kept himself busy with all manner of side hustles, from serving as a musical consultant on Cameron Crowe's Almost Famous to duetting with pro wrestlers on reality TV shows.

More than just show artists how to survive in an unforgiving industry, Frampton has shown us how to survive a seismic career upheaval with class and sense of humor intact. Frampton harbors no misconceptions that most people know him for one album and one album only. As he joked in a 2017 interview, "Look, no matter what I do, that is going to be the first thing that people say when I leave this planet: 'Known for…'" And he's never shied away from an opportunity to poke fun at his former-teen-idol-status by playing the straight man to TV's most obnoxious cartoon dads.

But most importantly, he's never lost the joy of playing for the fans who've stuck by him, even as the arenas and stadiums of old have been replaced by casinos and wineries. And that's why the news of his imminent retirement from the road is especially sad. Frampton's heart is still very much in the game, but his body can no longer keep up: Earlier this year, he revealed that he's been diagnosed with inclusion body myositis, an inflammatory muscle condition that will eventually impede his ability to play guitar. So this month, he's taking the talk box out for one last tour of duty that will wind down in October in Concord, California (located just outside the city that first made him a star, San Francisco). And when he sings "Do You Feel Like We Do" for the last time, it'll be a reminder that the song was never about a rock star demanding fealty from his followers, but the inclusive, self-effacing mantra of a guitar god who's always carried himself with the humility and grace of a mere mortal.