In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

Silver Convention - "Fly, Robin, Fly"

HIT #1: November 29, 1975

STAYED AT #1: 3 weeks

Disco music changed when the Europeans got ahold of it. In early-'70s America, disco was an underground club culture, one based around the gay and black bars of New York and the frisky R&B that the DJs in those bars would play. The music was an outgrowth of soul -- in particular, the luxuriant, orchestrated soul of Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff. A lot of the early disco hits in America were basically just fast, simple funk songs. But European producers heard those sounds and figured out something else to do with them. They mechanized those sounds, using drum-machine pulses to make the music into endless-repeat floor fodder, a sound completely removed from American funk and soul. That story -- which fundamentally changed both disco and American pop music in general -- starts with Silver Convention's "Fly, Robin, Fly."

A lot of the credit for the creation of Euro-discojustifiably goes to the Italian-born genius Giorgio Moroder, who will become an important figure in this column in years to come. But while Moroder and his collaborator Donna Summer were figuring out their world-shaping sound in Munich, they were also picking up tricks from two other Munich-based producers, both of whom were friends and collaborators of Moroder.

Sylvester Levay had grown up in what was then Yugoslavia, and he'd moved to Munich in 1972. There, he'd met his German-born collaborator Michael Kunze, a lyricist who'd started out writing German protest songs and showtunes in the '60s. Together, Levay and Kunze had gotten together to make "Save Me," a bubbling, insistent 1975 synth-disco track. They'd put together "Save Me" in four hours, using session backup singers and eventually deciding that they didn't need to finish the song. "Save Me," which barely has any lyrics, sounds like a backing-track demo. It sounds like a beat that's just sitting there, waiting for a singer to come in and add the lead vocal. But Levay and Kunze decided that they didn't need a lead vocal, that the song would be more interesting without one. They released "Save Me" under the name Silver Convention, since Levay's nickname was Silver. "Save Me" didn't chart in the US, but it was a hit around Europe, and suddenly Silver Convention had an identity, and a formula.

When "Save Me" blew up, Levay and Kunze figured out that they needed to make an album. That album, 1975's Save Me, was really just 10 different variations on "Save Me," and "Fly, Robin, Fly" was one of those variations. The lyrics of "Fly, Robin, Fly" are just six words, repeated into infinity: "Fly, robin, fly / Up, up to the sky." The singers who recorded the song didn't speak English, so it made sense to give them a short phrase, one that they didn't have to remember. Those words were effectively meaningless. They could've been anything. (Originally, the song was going to be called "Run, Rabbit, Run"; Levay and Kunze changed the words only minutes before recording the track.) For nearly six minutes, those words return again and again -- a prayer, a koan, a riff. They're simply part of the mix, a human face on a proudly robotic piece of music.

Around those six words, Levay and Kunze build a precision-tooled wonderland. The bass is insistent and endless, a merciless burble. The drum beat is even simpler: a kick and a snare, metronomic in their insistence. Around those elements, Levay and Kunze add flourishes: bongos, guitar-ripples, organs, strings. Those melodramatic strings are the only things that really recall anything about Philly soul. They're also probably the least effective thing about "Fly, Robin, Fly" -- distant echoes of the chintzy Love Unlimited Orchestra splendor that the Germans would soon forcibly eject from disco.

Before becoming half of the team behind Silver Convention tracks, Kunze had written music for actual German ads. Levay and Kunze certainly knew that they were making commercial pop music. But this was pop music that was confrontational in its minimalism. And Levay and Kunze almost certainly saw themselves as part of the lineage of art-music -- insurgents using disco as a vehicle to radically shift German music from its oompah past. The liner notes of the Save Me album claim that Silver Convention "belongs to a new generation of artists who have broken with the established image of German music." And it's probably not too much of a stretch to guess that Levay and Kunze saw themselves as kindred spirits of fellow German electronic pop auteurs Kraftwerk, who'd had a global hit earlier in 1975 with the 23-minute synth symphony "Autobahn." (Somewhat incredibly, "Autobahn," had peaked at #25 in the US, and the Autobahn album had even made it up to #5.)

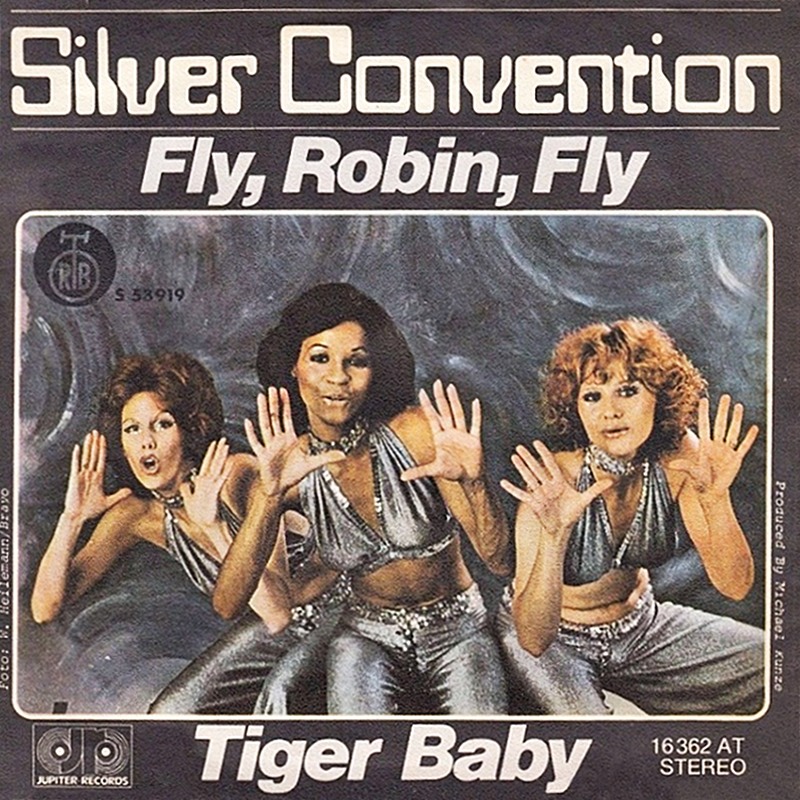

But whether or not Levay and Kunze saw themselves as artists, they still ran Silver Convention as a mercenary pop business. The same session singers who'd sung on "Save Me" once again added their vocals to "Fly, Robin, Fly." Those are not the women who we see on the "Fly, Robin, Fly" single cover, or in the video. In the process of transforming Silver Convention from a studio project into an actual functioning group, Levay and Kunze replaced the session singers with three women who'd all been individually signed to Jupiter Records, their label. These women were performers, so they became the faces of Silver Convention, even though they'd had nothing to do with making the actual music on the single. In their own way, then, Silver Convention were just as much a fictional pop construct as the Archies.

And just like "Sugar, Sugar" before it, "Fly, Robin, Fly" is effective machine-pop music. That bassline swallows you up, and the little things around it -- the dinky piano riff, the string line, the human voices -- serve to push it even deeper into your brain. But that same simplicity is also what undoes it. "Fly, Robin, Fly" was intended as utilitarian music -- music that would fade into the background while people lost themselves on the dancefloor. As a result, the song can become a little bit hard to take. The repetition is the point. But if you're listening to "Fly, Robin, Fly" in any context other than the dancefloor, a sound that starts out hypnotic and electrifying can gradually become exhausting.

Somewhat amazingly, Silver Convention were not a one-hit wonder, though we won't see them in this column again. The similarly single-minded 1976 single "Get Up And Boogie" peaked at #2. ("Get Up And Boogie," like "Fly, Robin, Fly," has a set of lyrics that only consists of six words: "Get up and boogie! That's right!" It's a 7.) After that, Silver Convention never got anywhere near the top 10 in the US, but they kept making music into the late '70s, and a lot of their tracks were European hits. The different members of the group also made solo singles, and Silver Convention represented Germany at the Eurovision Song Contest in 1977, coming in eighth with their song "Telegram." More importantly, they paved the way for Giorgio Moroder and Donna Summer, who would make the Silver Convention formula into something deeper and more sophisticated and who would radically reshape pop music in the process.

After Silver Convention finally went inactive, Kunze went back to writing music for the theater, while Levay moved to Hollywood and went to work with Moroder, doing arrangements for Moroder film scores like Flashdance and Scarface. Kunze also composed the themes for American '80s TV shows like Double Dare, Otherworld, and Airwolf. (His Airwolf theme fucking slaps.) Levay did his own movie scores, too, including The Creator, Mannequin, and motherfucking Cobra. That makes him a weirdly big part of my childhood, and maybe yours, too.

GRADE: 6/10

BONUS BEATS: Method Man and Redman interpolated "Fly, Robin, Fly" on "How High," an Erick Sermon-produced single for the soundtrack of the 1995 documentary The Show. "How High" peaked at #13 on the Hot 100. Here's the video, in which Meth and Red play Beavis and Butthead and then get into a helicopter chase:

(Method Man's highest-charting single is the 1995 Mary J. Blige collab "I'll Be There For You/You're All I Need To Get By," which peaked at #3. It's a 9. Redman, on the other hand, has never been in the top 10, a fact that I find upsetting.)