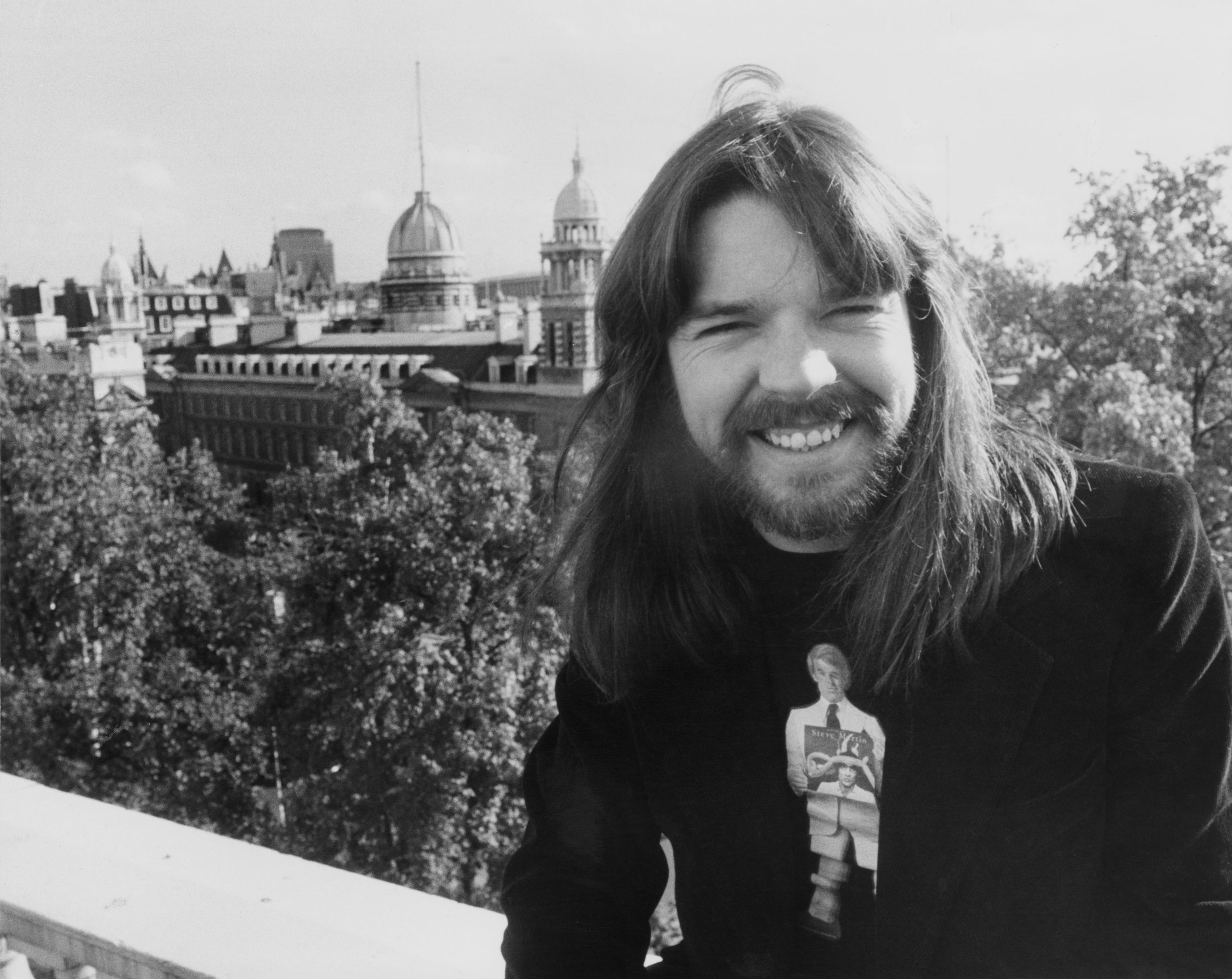

Bob Seger's "might be the strangest career in the history of rock and roll," wrote Dave Marsh in his 1978 Rolling Stone profile. Two years before, Seger, having spent over a decade working his way through a competitive Detroit rock scene and retiring a few times, had just broken through with back-to-back career-defining LPs: Live Bullet, one of rock 'n' roll's great live albums, and Night Moves, a contender for best car record ever. In 1978, he released Stranger In Town, arguably his best album.

Marsh, also from Detroit, was one of the great frenemies of Seger -- he often reviewed Seger with backhanded praise, cringing over a huge talent wasting his potential -- and he was relieved that Seger finally became famous. Like most critics and even some fans, Marsh admired the idea of Seger more than his actual music. He was holding out for the day when everyone, including Seger, would catch up. "These days," wrote Marsh, "an interest in Bob Seger seems much less exclusive ... Yet somehow, he's still the same guy who struggled for fifteen years to get any kind of break out of Detroit at all."

We're still catching up to Seger. Before he godfathered heartland rock, Seger was pushing forward the same proto-punk that his neighbors the MC5 and the Stooges would later perfect. When he got bored of that, he shifted from hot-shot guitarist and singer to full-time frontman, now writing songs championing the earlier, more playful rock 'n' roll that came from his childhood heroes Fats Domino, Little Richard, and Jerry Lee Lewis. By the time he got to "Turn The Page," he had lived that song for years. He meant every word of it. And when the rest of the world first heard Alto Reed's famous saxophone riff that kicks off "Turn The Page" on Live Bullet, they discovered what Detroit already knew: Bob Seger is one of rock 'n' roll's greatest songwriters.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Rock 'n' roll (not rock) songs like these now singlehandedly sustain the jukebox industry. Another such song is "Night Moves."

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

People love "Night Moves." People love talking about "Night Moves." There's a book of people talking about "Night Moves." It's a good song. "Night Moves" still holds up.

Another such song is "Old Time Rock And Roll."

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

You've heard this song. Even if you haven't, you've heard it. It's that song from Risky Business. It's the playlist deep cut to every Applebee's and some Olive Gardens. Go to any sporting event, wait seven minutes, and you'll hear Seger's boogie, which he technically didn't write, and see Randy and Nance swooning the night away. You've heard the idea of "Old Time Rock And Roll" your entire life. It's a fun song. It's meant to be fun.

If you're my age, "Old Time Rock And Roll" might be the opposite of fun. If you're my age, you may think this song represents the worst of baby-boomer nostalgia, a reactionary cancer that continues to strangle the earth and millennials, and that Bob Seger, who comes from the same city as Eminem and Kid Rock, is responsible for climate change, white nationalism, and late capitalism. Maybe that's true, too. Maybe both are true. "Classic rock can be a marketing scheme," wrote Steven Hyden in Twilight Of The Gods: A Journey To The End Of Classic Rock, "and it can also be transcendent." In an age where we're reevaluating the classic rock canon -- and the cost of transcendence -- is Bob Seger worth keeping?

There's also "Ramblin' Gamblin' Man," recently featured in Quentin Tarantino's Once Upon a Time ... In Hollywood.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

It's a good song. It might be Seger's most purely enjoyable song. A brilliant director and maybe the least self-aware human alive, Tarantino probably picked this song because it's a great car song. Maybe he wished he could crawl into Brad Pitt's car and drive off into the pre-Manson Hollywood night to the tune of Seger glorifying being a flake. Maybe it's satire. Maybe he's pulling a "joking not joking" troll for the sake of trying to make provocative art. Whether you think I'm overreacting or not going far enough will probably reveal how you feel about Seger, and maybe all of classic rock.

Seger has many litmus-test songs like this. He has albums like this, too. They all range from classics to classics for their time to just ... of their time. They're all at least fascinating, especially everything he released until 1980. When MTV came around, he happily bowed out to focus on touring for his fans and spending more time with his family. He passed the heartland-rock torch to John Mellencamp, a Seger fan and his equivalent in my home state of Indiana. (I grew up just a couple of hours outside Detroit, close enough to relate to the city's Midwestness yet far away enough to mystify it in my head.) Mellencamp, for better or worse, would later pass the torch to Kid Rock.

Seger remains present in strange ways. In 1987, he and his most famous collaborators, the Silver Bullet Band, earned a star on the Hollywood Walk Of Fame right outside the doors of his longtime label, Capitol. The same year, he earned his only #1 hit with "Shakedown," which might be his worst song. In 1994, "Against The Wind" was featured in Forrest Gump, another litmus test for your perspective on his legacy. To my understanding, he is the only inductee of both the Rock And Roll Hall of Fame and the Songwriters Hall Of Fame who has written a song specifically addressing climate change. He's sold over 100 million records around the world, and until two years ago, his music was almost impossible to find. (Much of his music still isn't available to stream.) He is the rock 'n' roll embodiment of the Midwest, in all its glorious down-to-earthiness and inferiority complexity; he nails that Midwest feeling of feeling like you have to earn your place in the world while constantly feeling out of place in it, a feeling he makes universal.

And you can't talk about Bob Seger without mentioning Detroit, or his actual hometown Ann Arbor. Seger is probably OK with that. "I don't think it was really a choice; it was where I lived and where I felt comfortable," said Seger in the photobiography Travelin' Man. "By being in Detroit, I can keep things in perspective and just work as much as I can but also have a life outside of it where I'm grounded and where people put me in my place."

Detroit is often credited as rock's great city. It might be more accurate to say it's one of music's great cities, which gave birth to two other important musical developments: Motown and techno. Seger would likely agree. Still, he does deserve credit for his involvement in Detroit's rock scene, which shared with Motown and techno a machine-like consistency and rhythm. (Berry Gordy produced songs like an assembly line; the Motor City Five changed its name to the MC5 because it sounded more like a car part; the Belleville Three turned steel into euphoria and called it techno.) Seger, who worked in an auto plant, would perfect this motor sound and evolve it into his classic rock 'n' roll songwriting.

Detroit also was home to some of music's great tastemakers, all of whom in some way would play a part in Seger's career. This was the city that produced Creem magazine, a middle finger to Rolling Stone and coastal media types who, still to this day, can't find Indiana on a map. ("He's a man of sanity and insight," Lester Bangs, Creem's most famous alumnus, wrote of Seger in 1978. "I respect Bob Seger as much as almost anybody I can think of in the music business today.") Other people who at one point called Detroit home: radio deejays Ed "Jack The Bellboy" McKenzie, Tom Clay, Robin Seymour, "Frantic" Ernie Durham, and a young Casey Kasem; the Grande ("Gran-dee") Ballroom's Russ Gibb; White Panther Party co-founder and MC5 cheerleader John Sinclair; and the Hideout's Dave Leone and Ed "Punch" Andrews. If you know anything about Bob Seger, you know Punch Andrews, who would become Seger's longtime manager. He is either the hero or villain of this story. There's evidence for both.

"Did [Seger] make Punch Andrews or did Punch Andrews make him?" said Mitch Ryder, one of maybe six other Detroit musicians who might have had a more direct impact on rock music than Seger, in Steve Miller's juicy, and contentious, 2013 oral history, Detroit Rock City. "I think Punch has done a remarkable job handling his image ... I just don't feel he served his fans as well as he could have." Later in the same interview, Ryder called Seger "one of the greatest writers we've ever produced." (It's worth noting that Punch also managed Kid Rock until 2007's Rock 'N' Roll Jesus.)

Seger was a hometown hero, even if he wasn't always beloved. Here's how Robin Seymour remembered a young Seger in Detroit Rock City: "Bob Seger did one of his first big live things at the Roostertail, where I was putting on events. He had his Beatles haircut, a little cap on, and he walked on the stage and had to walk right off; he was so nervous he had to go throw up. I went over to Punch Andrews, his manager, and I said, 'Get him out of here, I won't have anybody doing my shows on drugs.' Punch says, 'He doesn't touch drugs. He's nervous, he's scared to death.'" Mike Rushlow, also in Detroit Rock City, on an early Seger show: "Bob Seger wore this giant hat, and he came out [for a show], and the first thing he said was, 'Well, I'm not going to play any of my old stuff.' Everyone was like, 'Get off the stage! Where's the Stooges?'"

These are not the sexiest rockstar stories ever. No one is more aware of Seger's anti-rockstar qualities than Seger himself. "I've always considered myself an antistar," Seger said in Detroit Rock City. "I don't move well in a crowd, at cocktail parties, and such. I'm sure the Mick Jaggers, the extroverted rock stars do very well in that scene. But I'm an introverted person, basically ... it has nothing to do with developing a mystique or anything like that. That's not the way I am. I just don't deal very well with people I don't know."

Seger is equally humble (and honest) when speaking about his abilities. "I think my lyrics are stronger than my melodies," said Seger in 1994. "I wish I was as strong as Paul Simon, I think he's remarkable. I'm not a bad melody guy, but I'm not as good as others. I'm also not as good lyrically as Leonard Cohen, Tom Waits, or Don Henley. I think I'm just in between ... Some of my melodies are good and some of them are not so good. But I think I've been blessed with a voice that can put across certain things."

Seger might be a better songwriter than a rockstar, yet you can't imagine anyone else singing his songs. He captures that one-beer, small-town sadness better than anyone else, and any Seger narrator, for better or worse, could be Kacey's space cowboy. You go to other rockstars to project what you wish your life sounded like, with all its drama and fight-or-flight glory. You may go to Seger to hear yourself.

2019 might mark an end for Seger. His farwell tour is scheduled to end in Philadelphia a few weeks from now. By this time next year, one of rock 'n' roll's most underrated songwriters and live acts will have called it a day. One day, we will lose him, along with, for better or worse, the rest of the classic rock pantheon. Before that day, and while we still have him, let's take another look at Seger.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

The place to begin with Seger is his "latest" release, 2018's Heavy Music. Throughout the '60s, Seger fronted various backing bands experimenting with his songwriting and sound. The best songs from this exploratory era are on Heavy Music which highlights his better releases from 1966-67 with his band at the time, the Last Heard, all released on Cameo-Parkway Records. Come for the good-to-great garage rock via "East Side Story," "Vagrant Winter," and "Persecution Smith," stay for the bizarre Beach Boys-like "Florida Time" and the hilarious James Brown rip-off "Sock It To Me Santa."

To get a sense of what Seger was going for at the time: He made his TV debut with this hilarious lip-sync of "East Side Story" on Swingin' Time. (This passionate live drumming would give Japandroids a run for their money.)

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Most of these songs did OK locally and went nowhere outside Michigan. The title track was the first Seger track to chart nationally and was the first of several should-have-been breakthroughs. However, Cameo-Parkway went under, and the track remained a local hit. This devastated Seger. In his 1980 Rolling Stone cover story ("Bob Seger finally settles a fifteen-year score with rock & roll success"), he admitted to having suicidal thoughts around this time. It seemed like nothing would track. Seger, though proud to be a Detroit hero, was destined to only remain that. (This also was around the time Motown offered Seger a contract, and Punch Andrews declined.)

Towards the end of 1967, Seger would sign to Capitol, change his band's name to the Bob Seger System, and officially start phase two. It would start on a high note, even if it was underwhelming at the time.

In 1968, Seger released "2 + 2 = ?," his first Capitol single. Though he had mostly moved on from protest songs in the '70s (a notable exception is "U.M.C. (Upper Middle Class)"), Seger began his career writing decent protest songs with "East Side Story" and the anti-Vietnam War psychedelic jam "2 + 2 = ?" This is the only time you can ever imagine Seger coming from the same scene as the Stooges. More important, it's the rare Vietnam War protest song by a major artist that hasn't been overplayed. (To all the film producers who read Stereogum, all seven of you: stop using "Fortunate Son" and use this song.) This also is one of Jack White's favorite Seger songs; in 2017, the fellow native Detroiter reissued the single on limited vinyl through his Third Man Records. If you like the idea of the Doors but can't stand Jim Morrison, "2 + 2 = ?" might be more your speed, as it's one of Seger's best and strangest deep cuts. It also was his first of many flops on Capitol.

Fortunately, Seger's second single, "Ramblin' Gamblin' Man" would do better. After being out for months, "Ramblin' Gamblin' Man" reached Billboard's Hot 100 chart at the end of 1968. Seger finally had a national hit, one that features one of the better uses of the Hammond B-3 organ. It's the first "great" song by the Bob Seger most of us know today. (John Mellencamp, in his foreword to Travelin' Man, described first hearing "Ramblin' Gamblin' Man" in his friend's car and forcing him to pull over so he could listen to the entire song. "If there really is such a thing as Midwest Rock," wrote Mellencamp, "it started for me that night.") "Ramblin' Gamblin' Man" also featured the first studio gig of his good friend, Glenn Frey. ("We remained friends forever because we were not in the same band together," said Seger in 2018.) Frey sings harmonies and plays acoustic guitar as nice support in the background, which is more pleasant than anything he did with the Eagles. "Rambin' Gamblin' Man" was Seger's first Top 40 hit. He wouldn't have another one for eight years.

The following year, both "2 + 2 = ?" and "Ramblin' Gamblin' Man" would appear on Seger's proper debut LP, Ramblin' Gamblin' Man. It was originally titled Tales Of Lucy Blue and featured said Blue on an album cover inspired by The Birth Of Venus. The album is aggressive, loose, and, by Seger standards, weird. About half the songs qualify as decent riffs on the Rolling Stones, and "White Wall" goes between the Who and early Tame Impala. It's not a good Bob Seger album, but it might be his most overall enjoyable record. Seger would never touch this kind of sound again, which is a shame; what probably sounded bland at the time now sounds like a revelation.

One reason why Seger may have dropped this sound sooner than later: the album didn't sell well outside Detroit. Seger finally had a national hit, and it wasn't enough to make him famous. Still as stubborn as ever, Seger carried on and planned his next move. Turns out, Capitol had already decided his next move. Disappointed in Ramblin' Gamblin' Man sales, Capitol decided that Seger's next album, 1969's still hard to find Noah, would focus on guitarist Tom Neme as the lead songwriter. Seger became the sideman in his band. Seger responded by enrolling in college, believing that he was done with music. He was in school for six weeks before he decided to come back to music.

The Bob Seger System returned in 1970 for Mongrel. Those who have been able to find a copy say it's good, with "Lucifer," featuring new keyboardist Danny Watson, as the standout.

"Evil Edna" and a live cut of "River Deep, Mountain High" also are worth seeking out. Of course, nothing from the record sold well outside Detroit. Same goes for Seger's last Capitol record for a spell, 1971's Brand New Morning. Credited to just Bob Seger, this is the sound of someone running out of ideas as they pivot to the solo acoustic LP. ("Everyone has down periods," said Seger in David A. Carson's Grit, Noise, And Revolution. "The acoustic album was the depths for me.") In a 1990 interview, Seger said that the album was buried in his backyard, never to be seen again. This might be a joke. At least "Railroad Days" is worth keeping.

Meanwhile, Flint's now massively popular Grand Funk Railroad proved that you could bypass Detroit and gain national attention right from the start. This must have destroyed Seger, who had just finished out his Capitol contract and was essentially back to square one as a Midwest star. At the end of the year, Seger, with one of his other backing bands, STK, played the Free John Sinclair benefit concert, where John Lennon premiered "John Sinclair," a loving tribute to another scene legend and a pretty bad song. At least Seger sounded good that night covering Chuck Berry's "Carol."

1972 is often considered the end of the golden age of Detroit's rock scene. By the end of the year, the MC5, who for a while was seen as Detroit's great rock hope, were pretty much done. John Sinclair became the butt of his joke. Ted Nugent, who has always acted like Ted Nugent, began turning the Amboy Dukes into his backing band. The Frost, perhaps Detroit's most underrated rock band, had been done for years, along with countless other bands who became as big as Seger in Detroit but could not get a national hit. 1972 was a hard year for Detroit music, with Motown moving to LA the same year. Nixon's overwhelming defeat of McGovern that year served as a back-handed metaphor for the end of an era. Seger felt like it was the end of his rope, too. If he did call it quits around this time, Seger might have enjoyed becoming a cult hard rock musician. Luckily for Seger, who still very much wanted to be famous, rock 'n' roll was entering its glory days of arena rock. Now signed to Punch Andrews' subsidiary label, Palladium, Seger carried on. The next phrase of Seger had begun.

This next phrase was underwhelming. At first. Seger's first Palladium LP, 1972's Smokin O.P.'s, again only credited to Seger, was mostly a covers album that included the Leon Russell-written "Hummin' Bird" and "Someday," the sole Seger original. ("O.P.'s" stood for "Other People's Songs.") Next year, Seger released Back In '72. This album now is more important than good. It's the first album that features members of what would later become the Silver Bullet Band. It also featured Seger's first of many collaborations with the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section, who would become the secret weapon to Night Moves.

There's also "Turn The Page." The live version is still the defining take of this song, though the original version features that perfect saxophone intro that was specifically written to hit your feels in the gut. It's one of rock's great saxophone riffs, and I hope Tim Robinson, another proud Detroit son, uses it in the next season of I Think You Should Leave. That song, along with the rest of Back In '72, was the best thing Seger had done up to that point. Dave Marsh highlighted "Rosalie," which Seger wrote for CKLW's Rosalie Trombley and how she wouldn't play most of his records (she apparently loved "Rosalie"), and it would later be covered by Thin Lizzy. In his initial review, Jon Landau wrote, "[Seger] belongs at the very top of the rock 'n' roll heap. Back In '72 is just the record to put him there." Landau was right and wrong.

Seger's next album, his seventh, was called, uh, Seven, and it was released on Warner's Reprise in 1974 and later reissued on Capitol. Though it's still credited only Bob Seger, many see this as the first real Silver Bullet Band album. Now freed from balancing guitar and singing, Seger could now focus on being a frontman and, more importantly, a better songwriter. The most famous track might be the album opener "Get Out Of Denver," which Seger claimed never happened.

Though his albums were still not selling too much outside Michigan, Seger had now developed into a formidable touring live act, now opening for in-their-primes Kiss and Bachman Turner Overdrive. In 1975, he would finally level up on-record.

Now back on Capitol, Seger released Beautiful Loser, still credited as a solo album but featuring the Silver Bullet Band. Goofy and maybe, maybe-not self-aware album cover aside, you can hear the new and improved Bob Seger right away, with more involved collaborations with the Silver Bullet Band and Muscle Shoals. (After this album, the Silver Bullet Band became official.) "Katmandu," a not so subtle wish to escape the music industry, became the big hit, but the real winner is "Jody Girl," one of Seger's best ballads. There's also a cover of Tina Turner's "Nutbush City Limits," the most rifftastic jam to namecheck Labor Day, and "Momma," as if you needed more proof that Seger was a momma's boy. The following tour included Seger and the Silver Bullet Band playing a two-night stand at Detroit's Cobo Arena on 9/4 and 9/5 in 1975, which the band decided to record. Within a year, those live takes would make up Seger's first gold record and his national breakthrough.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=attPbjuxli0

1976's Live Bullet was released out of necessity. At the time, Seger's next album wasn't ready yet. After seeing how well Kiss' Alive! and Peter Frampton's Frampton Comes Alive! sold, and being smart (stubborn) enough to believe he put on a better live show, Seger decided to release his first live album as a placeholder between studio albums. (The legend goes that Capitol at first passed on Live Bullet because it sounded too similar to Frampton Comes Alive!.) Capitol made the right move. To this day, Live Bullet is still one of the best-selling live albums of all-time, and it's often called one of the best live rock 'n' roll records of all time.

Live Bullet is one of the best live rock 'n' roll records ... of 1976. Unfortunately, many Seger newcomers may find the actual sound of the album underwhelming. This can be chalked up more to the era than the actual performance. Charlie Allen Martin, a fine drummer, sounds like he's pounding a turkey sandwich. Even Seger is aware of the album's limits. "The performances were above average nights," he says in Detroit Rock City, "but not the peak of what the band can do. Technically, it's far from perfect." Far from perfect, but still compelling. The album is most famous for the live version of "Turn The Page," which is the version you hear on his 1994 Greatest Hits compilation. The album's highlight might be the one-two punch of "Travelin' Man" and "Beautiful Loser," or the killer cover of Van Morrison's "I've Been Working."

Seger had finally arrived. He would get bigger with his next album.

Robert Christgau called Night Moves, released a few months later in 1976, rock 'n' roll for "sweet sixteens turned thirty-one," at the moment "What if?" becomes "What happened?" The "sweet sixteens turned thirty-one" line comes from "Rock And Roll Never Forgets," Seger's best album opener, to what is perhaps the Bob Seger album. Seger was 31 years old when he wrote that song, and Night Moves explores that feeling of moving into adulthood when rock 'n' roll, which sounded fun and romantic at 16-years-old, now sounds terrifying or sad. It's also one of rock's great car records; Night Moves is one of only two CDs that I've ever destroyed from overplaying in my car. (The other is Green Day's Dookie, another perfect car album for different reasons.)

In an interesting twist, side one features the Silver Bullet Band while side two features Muscle Shoals playing behind Seger, even though the entire album is credited to Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band. The album is mostly lean and brings out the best of his songwriting. It includes his best album opener, songs that could have been on Exile On Main St ("Sunburst"), and a decent if somewhat cringe-worthy take on Sly & The Family Stone ("Come To Poppa"). "Mainstreet," inspired by Ann Arbor's Ann Street, might secretly be Seger's best song. Even his Eagles parody, "Ship Of Fools," is smarter than any actual Eagles song.

There's that title track, too. "It took a long time to write," said Seger in a 1977 interview on what might be his greatest contribution to the rock canon. "I wrote the first verse and then got stuck for two or three months. I wrote the second verse and got stuck again for another five months before I could finish it." The original song was called "Suicide Streets" and was Seger's attempt at turning American Graffiti into a song. He pretty much nailed it. At least Rolling Stone thought so; released as a single at the very end of 1976, the magazine named it the best single of 1977. Seger would get even bigger, and maybe even a little better, the following year.

A reason why Stranger In Town isn't considered Seger's best album might be because it came out right after Night Moves and was seen as Night Moves Part II. However, Seger's follow-up is compelling and is often stronger, albeit not as consistent. Unlike the wide-ranging Night Moves, Stranger In Town deals with a specific theme dear to many Midwesterners: the mystique of Los Angeles. Specifically, the album deals with how, when you finally take your chance and move out of the Midwest to follow your dreams, you realize it's not all that it's cracked up to be. You could read this as Seger coming to grips with finally finding national success and not knowing what to do with it -- the Midwestern boy in "Hollywood Nights." But you can still turn your brain off and drive fast to this entire album and have a time. "Still The Same," "Till It Shines," "We've Got Tonight," and "Brave Stranger" are all beautifully introspective, playing the sentimental sunset to a Tom Waits sunrise. And yes, there's "Old Time Rock And Roll." (Speaking of California, Seger co-wrote "Heartache Tonight" around this time with Glenn Frey.) Three winning albums in a row, Seger would get even bigger with his next album. There's debate if he got better.

"I was aiming for a totally commercial album," Seger told The Los Angeles Times in 1983. "Maybe it was a little too commercial, but I wanted to make sure I had three hit singles on it. I never had a #1 album and I wanted one." Seger sums up Against The Wind and the rest of his '80s better than anyone else. He also succeeded. Against The Wind became his first and only #1 album, and it earned him his first and only Grammy (Best Rock Performance By A Group). It's the sound of an artist who doesn't have to try anymore, which is the kind of artist who usually wins Grammys. This was the same year he landed on the cover of Rolling Stone; if anyone deserved the mainstream success at this point, it was Seger, even if he made the album equivalent of making out with Bob Ross. This also would be the last breath of Seger's roots-rock phase before he pivoted to the sleek '80s. The title track is one of his best songs, though sometimes I think "Long Twin Silver Line" is the better track. But other than those two, "You'll Accompany Me," and "Fire Lake," there's not much here to make you reconsider any ill will towards Seger. (Marsh called it Seger's worst album upon its release.) Later in 1980, Seger would record shows in Detroit and Boston for his second live album, 1981's also good but not as memorable Nine Tonight.

In 1982, Seger released The Distance, which is a good Bob Seger album produced by Jimmy Iovine. As I finish this sentence, I've already forgotten about the album. (Except for "Roll Me Away," a good song that sounds close to what most nerds think the War On Drugs are trying to do.) The Distance does have an interesting backstory: Seger was originally encouraged to release a double album, but he was concerned that fan would not be able to afford a double LP during a recession. This would become the first of many new albums that would help morph heartland rock into recession rock. A year later, Risky Business introduced teens to Tom Cruise and Seger.

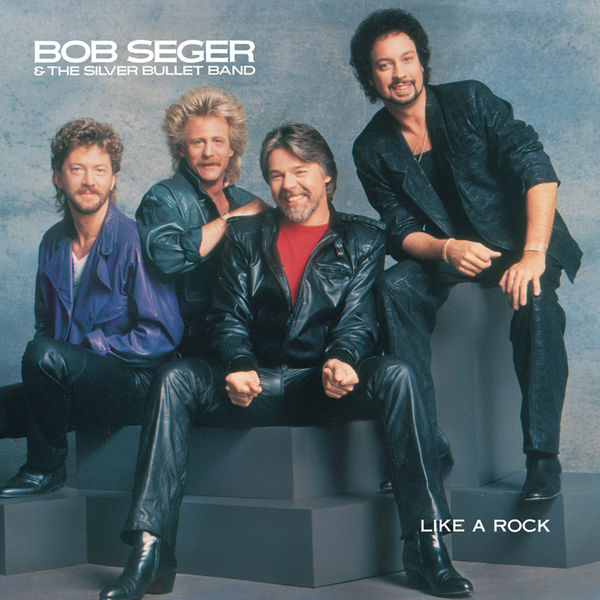

The next album, 1986's Like A Rock, is more memorable, but maybe not for the right reasons. First, there's the album cover.

And the album sounds exactly like this photo. It's as Reagan-core as the famous Chevrolet commercial that used "Like A Rock"; Top Gun, released the same year (hello again, Tom); and America's disastrous war on drugs. (Album opener "American Storm" is Seger writing about drug addiction, albeit a more nuanced take on cocaine abuse.) It was around this time that Seger wrote "Shakedown" for 1987's Beverly Hills Cop II. The song earned him a #1 pop hit and an Oscar nomination for Best Original Song. To this day, this is his only #1 hit song. It's a bad song.

Seger's next few releases, ranging from OK to not bad, marked a withdrawal from recording: 1991's The Fire Inside, in which Seger tried to sound like John Mellencamp, whom for years had been the new king of heartland rock; 1995's It's A Mystery, featuring the last Silver Bullet Band album full of new music; 2006's Face The Promise, Seger's return to music after a decade retirement; 2014's surprisingly engaging Ride Out; and 2017's I Knew You When, a tribute album to Glenn Frey that also features covers of Lou Reed ("Busload Of Faith") and Leonard Cohen ("Democracy").

Ride Out, though not available on streaming, is worth seeking out, as Seger seems, since at least the '70s, the most fired up about playing for and reaching a modern audience. In addition to a cover of Woody Guthrie via Billy Bragg and Wilco's "California Stars," Seger takes on debt, gun violence, and, most interesting of all, climate change, with the latter being the focus of "It's Your World."

"There's a UN report saying that climate change isn't 'coming,' it's here right now," Seger told Rolling Stone in 2014. "It stuns me that people like Marco Rubio, who seems fairly bright, would say climate change isn't caused by humans ... I've been told that a good deal of my fan base is Republican. But I don't think they all deny global warming. I think with a lot of them, cash is king and they want the jobs. I can understand that, but not if it's gonna wreck the future for our kids." (Seger to Rolling Stone in 2018 on Trump winning his home state in the 2016 election: "The second you get out of [metro-Detroit area], every rural area had a Trump sign. I never saw a Clinton sign. It was the rural people who elected him. They're very dissatisfied with Washington, and they thought he could do something different.")

Though he records less, Seger continues to tour to this day. And unlike other classic rock artists, he seems content with his elder statesman status. "An artist's biggest enemy is his history," Seger told Detroit Free Press in 2014, "it really is. So I'm up against that. It's an enemy but it's also a friend, because it makes you want to do better." After a scary neck injury in 2017, Seger is back on the road for what is pegged as his final tour. He was originally scheduled to play his final show back in Indiana, in the very same venue I saw him nearly 13 years before as a young teen going through the classic rock canon. I hope he keeps playing.