Last month, Travis Scott released Look Mom I Can Fly, a documentary centered around his blockbuster 2018 album Astroworld. The film spends a good deal of its time at Scott's concerts, where he's gained a reputation as a raucous performer who sends his youthful audiences into frenzies. The stage diving, the circle-pit-baiting, the shirtless dudes, the hypebeast attire -- that's all set dressing you'd expect if even remotely familiar with Scott's image and sound. But unless you or someone you love is a Travis Scott stan, it might surprise you to learn that, to many of those VLONE-clad novice moshers, this goes beyond turning up, and even beyond simply enjoying the music.

"In high school and shit, I was like, super depressed, I had no one to turn to," one young man tells the camera. "[Scott] was the first person to let me know that I wasn't alone." "He changes your heart," one fan near-tearfully gushes about the rapper. "He makes you feel love -- like somebody loves you out there." Another is even more direct, addressing the camera as if it were Scott himself: "You saved my life."

It's not uncommon for people to have such powerful, life-changing connections to their favorite music. It's a little more surprising when that's true for fans of an artist whose catchphrase is "it's lit!" and who's behind auditory bacchanals like "Sloppy Toppy" and "Beibs in the Trap" (this is gross oversimplification of Scott's artistic palette, but stick with me here). In outward appearance, swaggery, self-consciously hip hip-hop may not look like a salve for severe depression, and that's probably due in part to history. Got any clips of anyone saying that Puffy and Mase saved their lives? How about Snoop and Dre? This is a completely unscientific metric, but Google searches for Puff, Mase, Snoop, and Dre's individual names inside of quotes with "____ saved my life" all net results in the single digits. Travis Scott nets 236. It's not that those older guys haven't made heartfelt music with heavy themes -- they have -- and it's also not entirely because their heydays occurred before the blog era (Pink Floyd, the first old band that popped into my head, snags 198 "saved my life"s).

The usually-surly Travis Scott talks about one artist, and one artist alone, in the breathless way that his fans talk about him. That artist nets 5080 results for the Google search in question. That artist is Kid Cudi.

"I feel like he's part of my story... There would be no Travis Scott if it wasn't for him," Scott said of Cudi in 2015. "He came and surprised me at the studio one day when I was working with A-Trak and took me on this drive in his car, played me new music. It was one of those moments -- I was like crying in the backseat... He talked to me about everything. I felt like my life was complete."

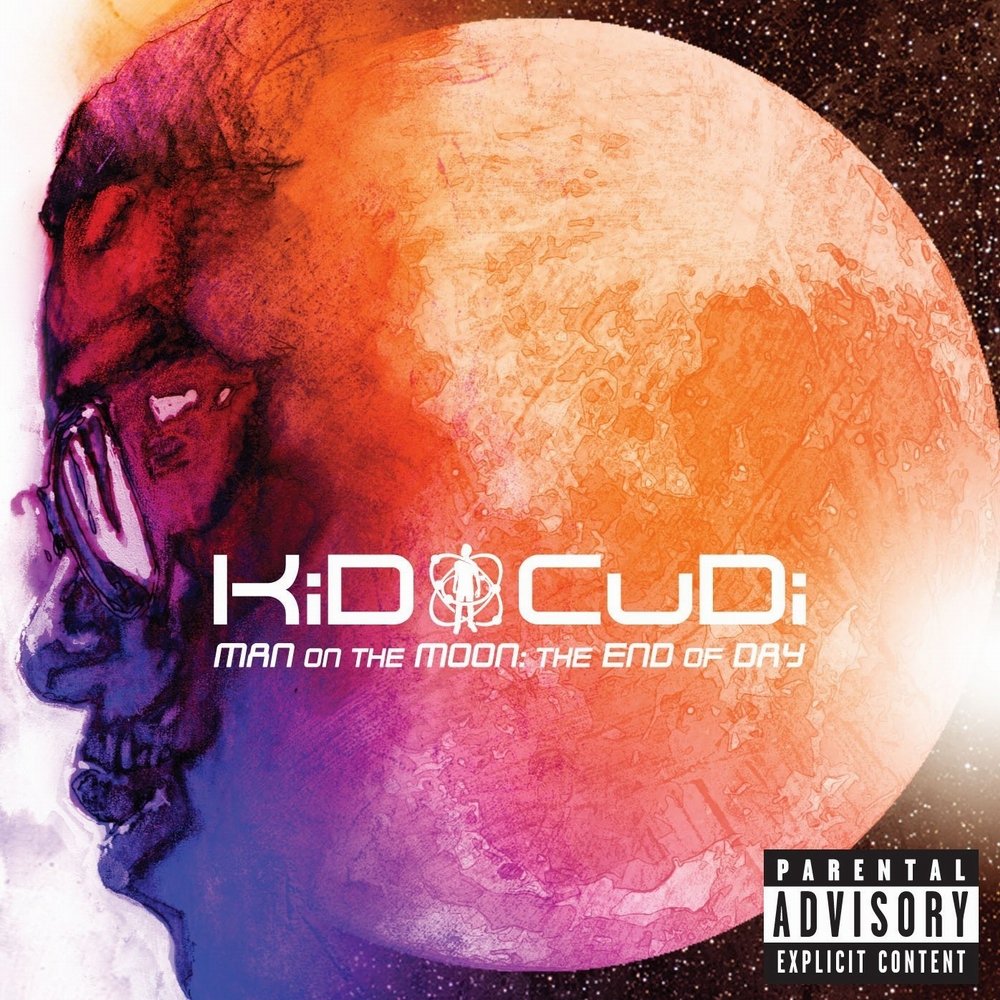

Scott's far from alone in his idolization of Cudi. Logic, Lil Yachty, Denzel Curry, Kyle, and Brockhampton's Kevin Abstract have all called Cudi's music either life-changing or -saving, to some degree. To rappers and rap fans of a certain age (or more accurately, below a certain age) who have struggled with depression, Kid Cudi has been instrumental in destigmatizing mental illness and addiction. He addressed his demons sporadically on his debut, the 2008 mixtape A Kid Named Cudi, but he didn't fully develop his whole therapy-with-swag approach until the following year's Man On The Moon, which turns 10 today.

Like catnip for late '00s blog omnivores and lonely stoners alike, the album's blend of introspection, pomp, druggy haziness, nerd rap, and indie rock was tailor-made for Kanye fans who also dug Vampire Weekend (whose "Ottoman" Cudi would freestyle over later that year), or Lupe Fiasco fans in the midst of the interminable wait between 2007's The Cool and 2010's Modest Mouse-sampling single "The Show Goes On." The synths are massive, the mixing is cavernous, the string sections are cinematic, the scope is grandiose. Every chorus sounds like Cudi's standing on the bow of a yacht with his shirt unbuttoned and flapping in the wind -- except instead of a yacht, it's the gaping maw of a black hole. "I've got some issues that nobody can see," he sings in one such instance, "And all of these emotions are pouring out of me." Indeed, MOTM cycles between all-out wallowing, escape via psychedelics, and inspirational anthems like a restless adolescent's take on the five stages of grief -- which may not be a coincidence, because Cudi chose to divide the album into five acts.

Cudi's choices to include "acts," to give the album a subtitle (The End Of The Day), to douse it in strings, and to get Common to do pseudo-Big Rube narration all over it may be overly dramatic, but they're harmless. Then he started shaming other rappers for not adopting similar gestures. In an interview with Arsenio Hall in 2014, he said, "The braggadocio 'Money, Cash, Hoes' thing needs to be deaded," adding, "I feel like if you're gonna be an artist, there's a time where you have to embrace the responsibility and understand that the power of music is so special and to be able to do it to a magnitude to reach millions of people." This explains Cudi's frequent use of low-denominator universalisms ("Why must it feel so wrong when I try and do right," "At the end of the day you can't regret it if you were trying," etc.) and it also shows that a sense of remove from the rest of hip-hop fueled Man On The Moon just as much as depression.

Closing out album opener "In My Dreams," Common calls Cudi "a voice who spoke of vulnerabilities and other human emotions and issues never before heard so vividly and honest." He's half right. Kid Cudi's on-record honesty was pretty game-changing, and apart from a few stylistic holdovers (such as the stadium synths at the end of "Heart Of A Lion" that sound like something Mike Dean would put on a similarly elephantine late-2010s Travis Scott song), his willingness to open up about issues that his most of his contemporaries refused to address is Man On The Moon's greatest legacy. But vivid? If anything, Cudi eschewed florid language for first-thought-best-thought venting.

As pedestrian as his lyrics can be, as ambitiously overdriven as his musical goals often are, Cudi is important to his fans in a way that transcends artistic merit. "[Man On The Moon] was more than just an album, it was a sonic therapy session," wrote Drew Landry last year for DJBooth, a site that, like Uproxx and Complex, often acts as the professional mouthpiece for Cudi stans. Those outlets surrounded last year's collaborative album with Kanye West, Kids See Ghosts, with wide-ranging claims about Cudi's emotive strengths, from the personal (Andy James' "How Kid Cudi's 'love.' Gave Me The Confidence To Conquer Loneliness") to the far-reaching (Aaron Williams' "Kid Cudi Helped Bring Mental Health To The Forefront Of Rap With Man On The Moon"). Just as Cudi makes artists who are hugely popular in their own right look like fanboys, he often inspires criticism that resembles a fanblog.

Some would have you believe Cudi was the first mainstream rapper to ever open up about depression. In his essay for Uproxx, Williams admits that earlier "underground emo rappers" like Slug, Eyedea, Blueprint, Murs, and Pigeon John covered the same emotional ground as Cudi on MOTM, but claims that "commercial, popular rappers like Tupac, the Notorious BIG, DMX, 50 Cent, and Eminem only found one outlet for those murkier emotions: aggression." Sure, aggression is the only thing that's fueling "Suicidal Thoughts," or "Lord Give Me A Sign," or "Rock Bottom," or the entirety of Me Against The World.

What separates Cudi from the angrier, gruffer rappers that came before him isn't emotional range, it's his ability and desire to forge an intimate connection with his audience. Amid all of the fans speaking about the healing powers of Travis Scott's music in Look Mom I Can Fly, Scott's go-to photographer, RAYSCORRUPTEDMIND, sums it up best: "He knows what the kids like, and he knows how to make the kids feel like a part of what he's doing." In 2009, Kid Cudi did exactly that. He made young listeners feel like they were heard, like he was speaking for them, while cherry-picking sounds (and collaborators) from recent hit albums like Kanye's Graduation and MGMT's Oracular Spectacular.

I was right in Man On The Moon's target demographic -- a newly-minted college freshman who almost exclusively listened to indie rock and hip-hop -- when it dropped. On release (or maybe leak) night, I gathered in my dorm room with three new friends and fired up the primitive (but trusty!) vaporizer my roommate and I had just purchased. The three of us absolutely lost our shit over the album. Just like vaping, Cudi was a then-nascent phenomenon that felt like the future. I can get high without my RA smelling it! I can be sad and still listen to rap!

Since then, weed's been large-scale legalized, as has sad-sack melodic rapping. It's granted some valuable perspective on the things I enjoyed at age 18. Newsflash: vaping might not be the safest thing in the world, but legalization has allowed for all manner of edibles and drinkables that eliminate the dangers of carcinogens and vape-borne illness. Similarly, Kid Cudi's debut may not be the most revelatory album ever made, but its success has allowed hip-hop to cover musically exciting and emotionally important territory over the past decade. Kids no longer have to smoke out of aluminum cans; rappers no longer have to feel like they're alienating themselves when they sing about depression over spacey beats. The world is a better place for it.