Adrianne Lenker and 2019's defining indie band have a way of drawing you in

I am trying very hard to make this orange look like an orange. But after trying my best to bring my illustration of Adrianne Lenker's snack to three-dimensional justice, I must concede that I have inadvertently drawn the sort of bowel movement that should make one hurriedly call their doctor.

This was not my intention. This is the third time something like this has happened this afternoon, and we just met 20 minutes ago. But her enthusiasm remains undimmed.

Lenker is the singer, guitarist, and songwriter for Big Thief, the most vital band of 2019. Back in May, Big Thief released one of the best albums of the year with U.F.O.F. Rather than ride the wave of acclaim, they're making a deeply uncustomary move for almost any band in 2019, let alone one who just experienced such a breakthrough: On October 11, they will release their second great album of the year, Two Hands. The two albums are very different, but taken together they demonstrate the range and emotional honesty that have quickly made Big Thief one of the most compelling bands working today.

In addition to her musical talent, Lenker is also a skilled visual artist. She mentions that she's never had lessons, and doesn’t practice as much as she’d like, but she’s thrilled that she gets to do so today. She says it’s all about showing up for yourself.

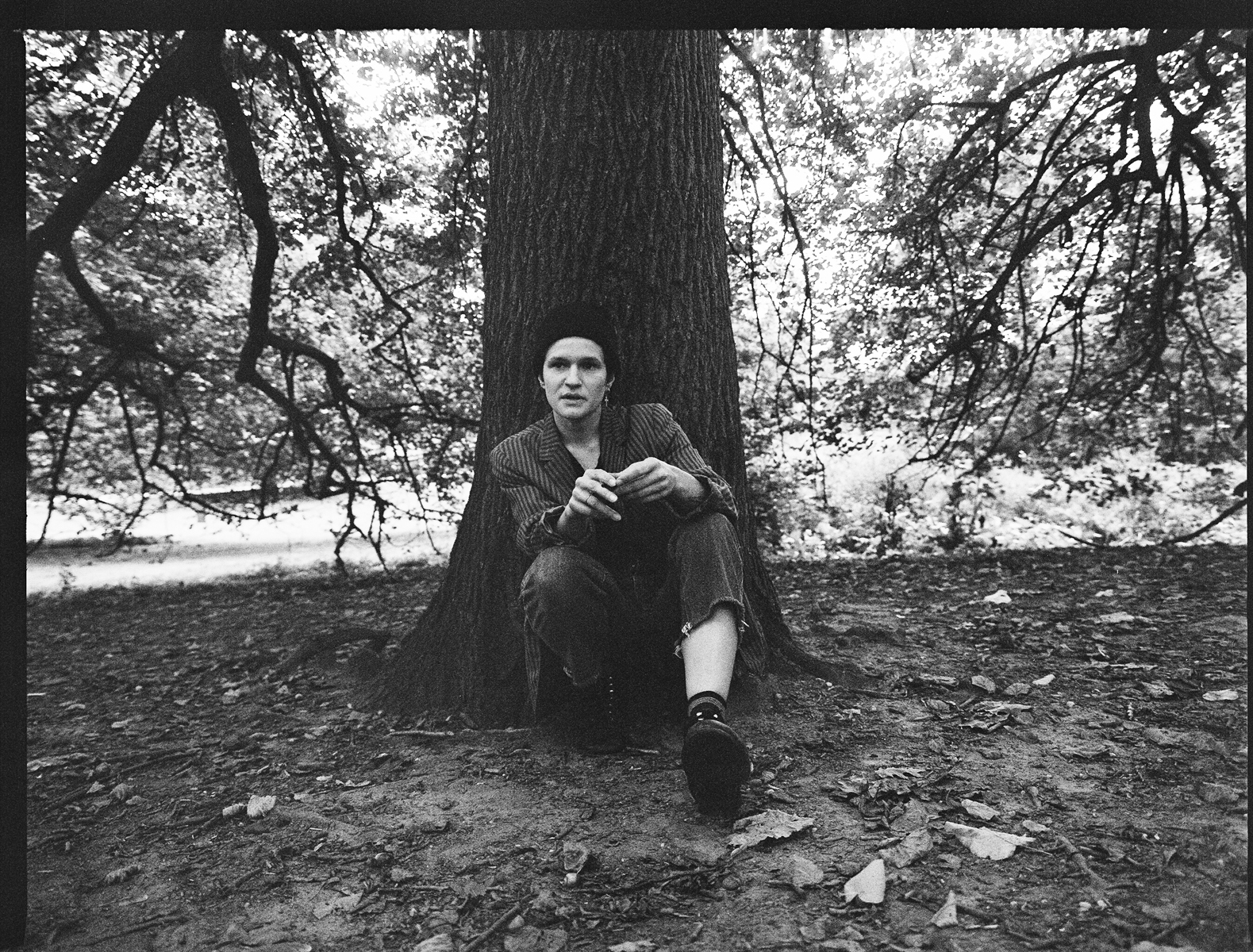

We're at Brooklyn’s Prospect Park on a Thursday afternoon to enjoy the last drops of summer and to draw together for a bit. She’s brought two sketchpads, colored pencils, and a multi-hued blanket for us to sit on. She shows me some of the drawings already in her sketchpad: a few rough drafts of concert posters that in my estimation are one coloring job away from being ready, and a delicately rendered portrait of her girlfriend, all while insisting that she wishes she was better at drawing. I find that a bit absurd, though I do relate.

"That’s beautiful that you call that an orange," she says, with a smile. I am 100% certain she is not being sarcastic. I am 80% certain she has never been sarcastic in her entire life. Maybe 85%. "Look," she says, flipping the sketchpad around and showing me her work. "I drew you. Or my impression of you." I feel like she has captured the existential befuddlement of my nature. I'm flattered and briefly chilled.

Big Thief’s music can very often achieve a beauty that feels as though it has always existed, speckled with the wisdom and humanity of Nick Drake and Joni Mitchell. In many ways, they seem like a band that could have existed and accrued a fervent fanbase in nearly any era from the '60s onward, sharing bills with Pete Seeger, R.E.M., or Vashti Bunyan. But fashion-wise, Lenker seems to be taking her cues from the early '90s goth scene today. She's wearing an inside-out black t-shirt with holes under the arms, black jeans, and black combat boots, looking like she’s ready to enter the pit during the club scene in The Crow.

We're both hard at work sketching the gigantic tree right in front of us. I’m doing my best (gotta show up for yourself), but my attempts to add shade and heft to my majestic pine just make it looked like its sad little branches have attracted a Pig-Pen-level of free-floating dirt. Her tree, of course, looks like it could be an illustration in a critically-lauded children's storybook.

"And they both look beautiful in their own way," she says, smiling.

I shake my head, just for a second, and then smile. "You're very kind," I reply. It's not possible to sound as earnest as Adrianne Lenker. But still, I try.

Her picture still isn’t good enough, she says. She can make it even better. She decides to add me to it. Then she goes to work on the branches. They can be even fuller, more in-depth, more vibrant, more beautiful, more real, more her. She pencils in more lines and more life. When it's time to leave, she adds one more line and lets go, leaving her latest masterpiece immaculately imperfect.

"But the one that I remember even more clearly, was the one that I wrote when I was 10," she continues. "That's when I really started getting in a flow of writing, and that one was called 'So Little Life.' It was basically what I still write about." Over the phone, she starts to faintly sing, her voice as fragile as some of the most exposed moments on her albums. "'So little life to live, so many words to say/ When I stop and try to say them, everything fades away/ When I drift out of this dream world, it's usually just in time to realize everything will be fine.'"

I was called to music because it was this thing that was always there for me that I could pour my heart into safely.

Lenker is, as you have probably surmised by now, an extremely polite person. As such, I get the sense that she is too nice to not at least make an attempt to answer a question that I feel obligated to ask for the sake of completeness -- even if I can tell she’s not exactly thrilled to be talking about the more headline-ready aspects of her backstory, as she perhaps senses that it could overshadow her already voluminous musical achievements. When I ask if music was the outlet she needed to deal with her tumultuous family life, she gently downplays the idea.

"Well, I mean, it was strange. That religious group was interesting. But also there was conflict beyond that," she says. "We all need ways of processing things. I think I was called to music because it was this thing that was always there for me that I could pour my heart into safely."

On the blanket in the park, we discuss spirituality for a bit, as is only natural when one talks to Adrianne Lenker. She says there's "not any one religion or faith that I've subscribed to, but I value all perspectives, because I think that there's so much to be gleaned from many different religions and spiritualities. I don't like it when religions take it to the point where they discredit all other religions, because how could one sector of people have figured it out and know that that's it? But I do think that there's so much beauty in a lot of the stories or scriptures. And there's so much more studying that I want to do."

When asked if her upbringing turned her off to stricter religious observance, she replies, "I never went through a wave of hating Christianity, even though my parents were born-again Christians, and there were a lot of ideas that were being practiced that I think were misguided. 'You're going to hell if you do this or this or this. This is evil. This is sinful, to watch these films or to let the Bible touch the floor or to pray without a head covering or to name your children non-biblical names.' That kind of stuff just didn't resonate with me. But I still never discredited Christianity because I have friends who are Christian, and we can have perfectly beautiful conversations, and I'm like, 'Wow, that's a beautiful perspective.'"

Her dad started taking her to open mic nights when she was 12, and it was indeed as awkward as you might imagine. “People were always like, 'Whoa, she's only this age and she's doing this?' I was always the youngest person in any group. I had a band and I didn't go to high school, all my friends were older than me," she remembers. "It was pretty cool to have such a focus at that age, but also it alienated me from a lot of people my age. So I felt pretty lonely and I didn't really have many friends when I was a kid."

She stresses that this was her decision: "It wasn't imposed on me at all. I wanted it." Her dad was managing her, and raised money from investors to record a few albums. "Naturally, as I was only 13 or 14, I wasn't really old enough to have all the tools and mechanisms to realize my own vision, so I was just part of the vision of the producer and my father and the people around me," she says. "It was basically my schooling because I was always in the studio, but when we finished the project, I was kind of like, 'Holy hell.'"

"Think of how much you grow between 12 and 14 years old," she continues. "I got into Elliott Smith and Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen and I was like, 'This doesn't resonate with me. I want to make music on my terms and in a different way and I don't even know what that is yet, but I think I want to go to school.'" She decided she wasn't ready for a music career just yet, and instead wanted to learn more about "my craft." (You can find her teenage album from 2006 if you look hard enough, though she doesn't consider it part of her official discography.)

It was difficult for her to break the news that she wasn't ready. "I had to separate from my dad because that's naturally what happens anyway when you're a teenager, you push away from your parents," she says. "But I had this added layer of a music career that was tied to him." After earning her GED, she went to the Berklee College Of Music on a scholarship provided by Susan Tedeschi, singer and guitarist for the Tedeschi Trucks Band.

When I ask her if she ever wonders what her life would be like if she had gone ahead and pursued her music career at the age of 14 and perhaps had achieved an '00s style guitar-pop teen idol career analogous to Michelle Branch or Avril Lavigne, she shoots the idea down as forcefully as I've her heard talk in the time I’ve spent with her.

"I just don't think it would have been possible for me. I'm too stubborn," she says. "I think I would have been like, 'This goes against my spirit. No thanks.' I just don't think I would have been able to melt into it at all."

Meek grew up immersed in music in the small town of Wimberley, Texas. His mother gave him his first guitar lesson when he was "five or six," he tells me over the phone in early September. "My little hometown was this refuge for a lot of the old outlaw songwriters and Austin musicians from the '60s and '70s who moved out whenever the tech bloom blew up there," he recalls. "So Ray Wylie Hubbard and Butch Hancock from the Flatlanders and some of the guys from Bob Wills' band were out there. And they all took me under their wing, one way or the other."

He began playing rhythm guitar for old-school types such as Slim Richey, "who played with Herb Ellis back in the day," and Django Porter, who'd played guitar with Merle Haggard. He would perform with their bands at roadhouses, barbecues, private parties, funerals, weddings. "But not for money necessarily," he says. "Just for the love of it." Though the musicians were all in their 50s and 60s, Meek doesn't recall anyone thinking it was strange that they had a 13-year-old guitar player in their band. "In Texas, I think it's part of the culture," he explains. "It's passed down through the generations like that."

The summer after he graduated from Berklee, his ragtime band Mobtet played with Lenker's unnamed group, which "was just blowing my mind," he remembers. "And she was so incredible. Everyone was dancing."

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=oacUgWXrqwc[/videoembed]

Lenker had already released a solo album, the first one she really counts, called Hours Were The Birds. She was considering moving back to Minnesota, where her family had settled, after graduation, but decided to give New York a chance as she'd had a nice time playing Manhattan’s Rockwood Music Hall one afternoon with her band. Meek and Lenker met the first day she moved to New York. "She had just stopped into Mr. Kiwi's to get a juice on her way to the first apartment,” he remembers. They ran into each other at the grocery store and he offered to show her around the city.

"She's opened up, I think, more with all this traveling. But at that point, she was pretty reserved. And she had this gaze that would just like cut through you like a snow wolf," Meek says. "You would be speaking to her and she'd be looking at you so intensely. She'd be listening very deeply but not humoring you with any kind of response."

They quickly fell into a musical rhythm, "playing old John Prine songs and writing songs together." "All she wanted to do was play music," he says. "I think pretty quickly it was clear that we had chemistry, and I think it was mostly rhythmic. Her guitar parts are really intricate, but there's a lot of asymmetry in the fingerpicking. They're super rhythmic but they are kind of crooked. The time's changing a lot but there's this pulse, and I had been playing rhythm guitar my whole life, so I think I was able to tap into that with her." They started playing house shows and eventually started touring as a duo, cutting the collaborative A-sides and B-sides EPs together during off-hours at the studio that Andrew Sarlo, Lenker's friend from Berklee, worked at. And then at some point, Lenker saved up enough to buy an electric guitar.

"She started writing these heavier, more rock 'n' roll songs. And so we figured we needed to build a band around that," Meek says. They found drummer Jason Burger, and Meek then ran into bassist Max Oleartchik, who he had met years ago when they were roommates at a Berklee Music summer program for teenagers. He didn't even know his old friend had come back from his native Israel, until they ran into each other on the street in Bushwick. "We needed a bass player and he just walked up to us, basically," Meek says. "Manifested for the band."

Meek and Lenker named the group Big Thief after an idea they learned in a songwriting workshop in Texas about "a trickster or thief that borrows from the collective conscious, and regenerates ideas and integrates them into his or her identity." The newly formed quartet recorded Masterpiece with Sarlo and engineer James Krivchenia, who took over for Burger when he left the band. "It marked the beginning of our creation, our creative process together as a band," Lenker says. Regarding the title: "It was a joke in a way, because if this album is just all of us putting our hearts in and it's the best we can make, it already is a masterpiece being what it is."

They recorded the follow-up, Capacity, six months later, shortly after signing with Saddle Creek. The next time they hit the recording studio, they would only take five days between albums.

"It has been two years, and in that time Adrianne had just written so many songs. She writes a lot. So there were 50 songs that we felt could go on the record," Meek says. (In case it wasn't already clear just how prolific Lenker is, this was after already releasing a solo album, abysskiss, late last year. By the time Two Hands arrives, she will have released three albums within 12 months.) "For a month we went through every song and built arrangements and hashed them out."

It quickly became apparent to the band that they had two albums' worth of material. But Lenker says, "We didn't want to make a double album, because we felt it was too dense, especially for these particular songs. We just wanted each to have its own focus, and so pretty early on, we knew that we were going to make two records, and we knew that we wanted them to be very contrasting."

Big Thief, Sarlo, and engineer Dom Monks went to Bear Creek Studios in rural western Washington last summer to record U.F.O.F., an entrancing collection of cosmic folk songs that was immediately deemed a classic and one of the year's best when it was released in May. A few days after they finished work on that album, everyone went down to the Southwestern studio Sonic Ranch in the small town of Tornillo, Texas, about 30 miles away from El Paso, to record Two Hands, the more visceral and earthbound of the pair. If U.F.O.F. is the spirit, then Two Hands is the body.

"I feel like they're siblings. They come from the same place, and all the songs were written in the same time span, and they were forming in the womb of all of our spirits. So there's some connective DNA, but they're very different beings," Lenker says in the park, remembering the two albums' origins.

"U.F.O.F. is meant to be more focused on the immeasurable, sort of suspended ethereal playing with textures and colors and layering in the production, staring out into the abyss," she says. "And Two Hands is more the micro, zooming into the blood and tissue and guts of being a human, the raw, bare, naked bones, not much layering, capturing just our performances in the room, just very dry, no reverbs, just skin and flesh and human, finite, physical. But I think each of them contains parts of the others."

The parallelism extends beyond the sound of the two albums and into their subject matter. U.F.O.F. is about being comfortable with the unknown, leaning into the mystery of life, of accepting that life is a moment that will pass, and you can embrace that or not. "You let go of everything you have, of everyone you love and even of your own body throughout the course of this life," she says. "You could be completely numb to it all, but then you wouldn't feel the incredible beauty of experiencing all of that as well."

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=AjPa7M5n2CU[/videoembed]

If U.F.O.F. concerns matters of impermanence and the greater mysteries of the world, then Two Hands is very much about the practical realities of life on Earth. Here, Big Thief show their skill at writing searing, perceptive songs about the ills that never seem to go away. "The Toy" addresses gun violence; "Shoulders," police brutality; and "Forgotten Eyes," homelessness and "the unheard voices that exist." There are also plentiful outcries in the album, such as on "Shoulders" and "The Toy," concerning humanity's ongoing destruction of the planet.

"I keep trying to break through the numbness that washes over everything, that keeps people from being awake, where you can feel that rush of clarity that you're part of the earth and that you feel something that's connected between all of us," she says. "I've just been trying to find a way to write about things from a place that I know resonates within my core rather than just stuff I agree with. How can we reach people? We're taking more than we need and depleting and wounding the earth, and we can all feel it."

Big Thief are a band guided by instinct and feeling. They never like to overthink anything. "I don't think we should ever play anything more than we should ever have to," Lenker says. "Once you play a song seven times, you're going downhill -- for us, anyway. It's usually within those first few times of playing it that it's the best, even if it's full of imperfections." When the band thought they were rehearsing the single "Cattails," a jaunty ode to making peace with feeling infinitesimal that Lenker had finished that morning, Monks secretly began recording them, and that's what you hear on U.F.O.F. "We walked into the control room and it was captured, that was it," she says. "We didn't have to work at it at all."

In contrast to the wash of spectral bath of its sister album, Two Hands has some of the loudest and most caustic songs that Big Thief have done yet, including the protest anthem "Not." "We were in Texas and it was like 120 degrees," Meek says, "And so we just went for it."

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=UIcVwH47uxQ[/videoembed]

They all decided to focus on live takes, with few overdubs for the album, giving them even less room to think too much. "There's got to be some inherent magic that just makes you feel everything, and then you go from that, never building on something in order to fix it or to mask it," says Lenker. "We would play a song, and we'd hear it back in the studio. That had to be it. We're not going to add much."

Ahead of U.F.O.F., Big Thief left Saddle Creek and signed with 4AD, the sort of independent label for whom the term "venerable" is too small; Meek is especially happy to be on the same label as the Breeders and Cocteau Twins. The band knew it was the right fit when Ed Horrox, head of A&R, heard their early demos and started air-drumming along.

Big Thief are, at best, indifferent to the business side of the music industry, and much of their music feels out of time, divorced from any particular current style or movement. (I was surprised to discover the band members all have personal Instagram accounts.) "I don't really study the trends so much, but I tune into things that make me feel something -- and that's all over the place," Lenker says. She proudly claims: "We're song-based, definitely, and record-based, and not just singles on Spotify. We always think of things in terms of how it would translate on vinyl." The band's managers and team were largely supportive of the idea to put out two albums in a year, even understanding that the second album might not receive as much attention compared to U.F.O.F. Though Meek says there were some devil’s advocate arguments about whether the band might confuse listeners or flood the market, Big Thief ultimately felt it was best to do what felt best.

"Even though they were separate, we wanted to express that they were very related," he says. "And we felt like more than six or seven months in between records would dispel that truth a little bit."

While they might not be headlining Coachella next year, success has just increased for them nonetheless. This fall, they’ll be headlining some of their biggest venues on an extensive tour, and the breathless reviews for U.F.O.F. and Two Hands' lead single "Not" have helped secure their reputation as artists that came out of nowhere in the latter part of the decade to become one of the best bands of the '10s. As the crowd sizes and the acclaim grow, the struggle for Big Thief is to stay connected, both to their audience and to themselves.

"I think a huge part of it is just like finding that clear pathway between ourselves and the audience," she says. "And if there's some blockage between us and the audience for some reason, like, for instance, at festivals sometimes it's really hard to feel the audience because they're standing so far away and everyone's attention is scattered. In those cases, we really have to zoom into each other."

They’re determined to not let their live show get too static, and they recently did Two Hands in its entirety live in London months before the audience had heard it, just because they felt like it. Big Thief already seems like the type of band where if you like the current album, you had best see them on tour as soon as you can, because there's no guarantee that any of your favorites will stick around.

Once again invoking the phrase "showing up for yourself," Lenker excitedly describes the nagging feeling that sets in every time her band writes up a setlist of old favorites, the irresistible pull to keep nudging themselves and their audience forward into unknown territory. "And that is what I feel like Big Thief is doing in the world," she continues. "More than just performing or making cool music that people can put on and vibe out to. I feel like we're actually practicing the art of pushing ourselves into a space that feels vulnerable, publicly, and not being afraid to grow and learn."

Meek says that early on in their career, Big Thief would focus on "blowing the roof off" the tiny venues they were playing. But now it's a bit different. "The bigger the shows get in capacity, I feel like the more intimate we dig in," he says. "It catalyzes us to be physically tighter on stage. Our stage plot has gotten smaller and smaller and smaller the bigger the shows get. At this point we're basically touching each other. My guitar head is constantly hitting into the cymbal."

Big Thief do not bring a lighting person on tour, none of the members wear the in-ear monitors that most musicians use to hear themselves while they play, and Krivchenia does not play on a drum riser, which Meek says tends to annoy the hell out of the stagehands at music festivals. All four of them play together all in a straight line in the center of the stage, practically on top of each other, the intention being that all of the members can maintain eye contact with each other throughout the entire show. Or additional contact, if need be. "Max can just walk up behind Adrianne and put his head on her shoulder if she's having a hard time," he says. "We can actually take care of each other because we're not isolated in our little worlds on stage."

The bigger the shows get in capacity, I feel like the more intimate we dig in. At this point we're basically touching each other.

Everyone in Big Thief lives all over the place. Lenker, 28, is technically homeless, though she calls herself "homeful" as she is at home as long as she is near people she cares about. She's about to sublet a place near her family in Minnesota. Meek, 32, lives in Topanga. Krivchenia, 30, lives in Los Angeles, where the band will rehearse before their tour. And Oleartchik, 32, moved back to Israel -- "between the mountains in Tel Aviv," Meek says. "It's this new chapter of taking care of ourselves first instead of sacrificing everything for the music," he says of the arrangement. The band has check-ins by phone every Monday, which usually include saying no to a lot of business opportunities they find distasteful.

"It's such an insidious little thing when the industry starts to permeate into the garden of our music. I feel like that can happen without even realizing it, just slowly through tiny, tiny, tiny decisions," Lenker says. "There's always a list of things, like so-and-so wants to use your song for this, or so-and-so is wondering if you'll do this ad for this, or hey there's this private party and it's sponsored by this company. Whatever it is, it's people wanting to do something with our band because we have authenticity. And the question usually comes down to, 'Would we be doing this if absolutely no money was involved?' And it's like the answer has to be yes, because we have to believe in it at every step. But then the steps increase exponentially."

Lenker doesn’t sound too concerned with how to keep her art from getting turned into a commodity. She has much bigger plans that would preclude such an outcome. “I don't think we just want to be a touring band for the next 20 years and try to get as big as possible," she says. "I think Big Thief's going to be really creative in the future. I think in the next 10 years, we're probably going to find some way to protect some patch of the earth and maybe build a studio and have underprivileged children be able to come and make music, and give kids a voice and help record their music and tap into a network of all these musicians we've met along the way. And maybe create something where we could also have a giant vegetable garden. We want to create something that would help, not just donate money we get from tour to organizations but try and grow closer to the earth, closer to our own centers. And I don't even know how it'll look.”

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=dUR-Ad8QcmA[/videoembed]

For now, while still maintaining a heavy touring schedule, they try to at least stay connected to each other. On the road, they try to eat together as much as possible. They hike together, too, and they talk to each other. A lot. As much as possible. "We respect the process of communicating. Whatever the issue is, everyone's getting together in a circle and talking it through until it feels harmonious," Meek says. "Everything is democratic in our band, creatively and with business. Everything has to be agreed upon, which is so exhausting, and it takes so much more energy than just Adrianne or me being the bandleader. It was an evolution. At first, me and Adrianne built the band, so we led it together. Pretty quickly it became this unanimous democracy."

The album covers for U.F.O.F. and Two Hands feature all four band members practically on top of each other, and that's not a coincidence, that's a message. "We saw the photos and we decided, 'This is the simplest, most honest expression of who we are as a group of people,'" Meek says. "We just actually want to be that close together whenever we're hanging out because we love each other."

In the fairly short time Big Thief have existed, they’ve learned how to be a true band, how to protect each other and their music, and how tough and brave and rewarding and hard it is to be vulnerable in public. "It's an endless stream of learning," Lenker says, one that she doesn’t want to stop. In 2019, they established themselves on a different level, but in many ways Big Thief are just beginning. Lenker hopes they’ll always be just beginning. She doesn’t think about what they’ve accomplished, or in terms of accomplishment. She’s just thinking about showing up for herself and her band every day. And you, if you need her to.

"It's the feeling of being pulled towards something that ... it's hard to explain exactly what it is," she continues. "I get the most fulfillment in the day-to-day of something about showing up to a new place, meeting the person who works at the gas station, something about climbing back into the van or the bus with my bandmates, that feeling of tearing down my instrument at the end of the night. Since I was a kid, how many times have I put my guitar away? There's nourishment in that."

We say our goodbyes, and I thank her again for being a great art teacher. She tells me I have a nice presence, which is not something I've heard before but it is something that I suspect is probably high praise coming from her.

As we prepare to leave, she picks a leaf off the ground. It's got an orange-brown hue around the side, but a spark of green still in the center. It’s still transforming, young and old simultaneously. She places it in her backpack, just in case she needs a little bit of beauty along her journey.