Among other things, Creed's second album holds the distinction as the only piece of recorded music I've been punched in the face over. I was at a house party in the summer between junior and senior year of college (2008, if you feel like doing the math as to how old I am), and a track from Human Clay -- "Higher," if I had to take a guess -- started blaring from the stereo. (This was in suburban New Jersey, so the question of whether this musical selection was ironic or sincere is quite literally impossible to answer, and potentially dangerous to ask even in polite company.) I good-naturedly turned to a high school friend and reminded him of the time in freshman year -- 2001, right around the time that the vaguely holistic neo-grungers released their third LP, Weathered -- in which he claimed that Human Clay could hang with Led Zeppelin’s best. The next thing I knew, I was socked straight in the face, stumbling out of the party and being told not to come back as I asked what I'd done wrong.

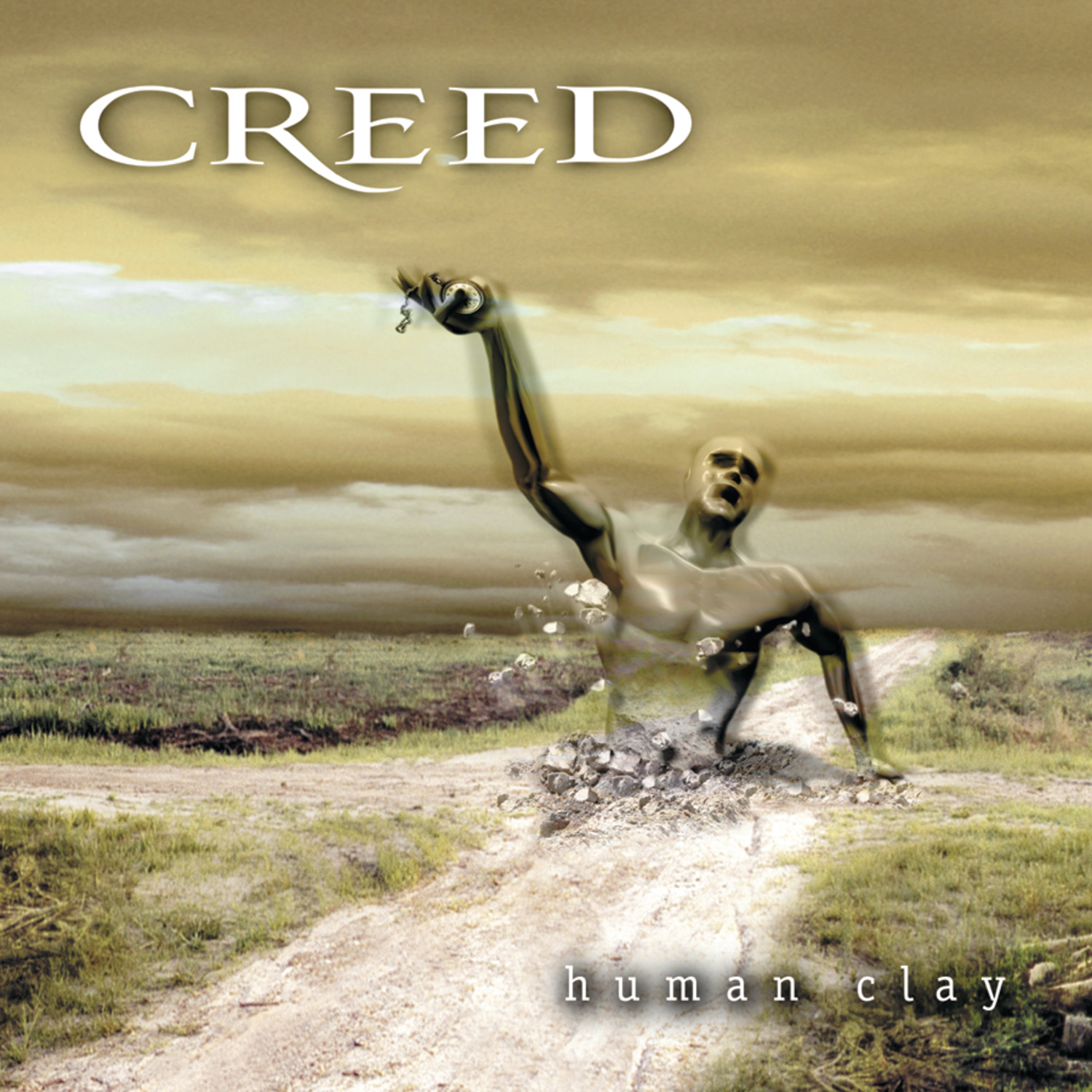

Me and my friend are cool now, but Human Clay isn't. The monstrously popular album turns 20 this Saturday, a milestone that is as much a reminder of how quickly time passes as it is a fact-check against the common assumption that Creed’s perpetually ascendant, last-flag-flying rock music is emblematic of the George W. Bush era's jingoistic vagaries. Some music tends to sound better with age, while other music tends to sound worse. Two decades on, Human Clay simply just is, a thunderous and immovable slab comprised of sepia spirituality, chugging riffs, and bandleader Scott Stapp's medium-maned caterwaul. If you've never heard it before, there are no revelations to be found here; if you were part of the record-buying public when it was released, there's a solid chance that you remember more songs on this thing than you think. (And if you're the type in search of some solid gym music, I can report without shame that it makes for a good treadmill soundtrack.)

It's impossible to overstate how massive Human Clay was upon release. Its predecessor, the 1997 debut My Own Prison, peaked at #22 on the Billboard 200 and impressively went on to go 6x Platinum; Human Clay sailed past Diamond status (that's 10 million copies shipped) and spent two weeks at the top of the charts, selling over 300k copies in its first week at a time when selling 300k copies meant moving pure physical product. (In the last 10 years, only one album has gone Diamond: Adele’s similarly massive 21 from 2011.) If the singles from My Own Prison were emblematic of late-'90s rock radio's grunge hangover, Human Clay's widescreen blare broke through to the mainstream well beyond the FM dial. A common reaction to the music Creed trafficked in during their prime was, "Who wants to listen to this?" But revisiting the blindingly bright melodies spread across Human Clay's canvas, it's easy to hear why the album achieved such staggering popularity, even sending a rock power ballad to #1 at the height of the teen-pop craze.

Familiarity played a role, too. Like so many of their post-grunge peers, Stapp and company more often than not resembled a faded facsimile of the arena-rock glories of Pearl Jam circa Ten -- a similarly massive rock album that could ostensibly be termed the Human Clay of the early '90s (apologies to all the Pearl Jam fans). Ironically, Pearl Jam were in a very different place sonically and career-wise around the time of Creed’s ascendance, having spent most of the decade rejecting the trappings of the music industry that Creed so benefited from. A year after Human Clay was released, PJ would put out Binaural, one of the Seattle heroes' most underrated albums and a moody slice of alt-rock that had more in common with OK Computer than Vertical Horizon.

"Eddie Vedder wishes he could write like Scott Stapp," bassist Brian Marshall claimed during an interview with Seattle radio personality Andy Savage in 2000, going on to slag Pearl Jam in their own hometown: "Looking at their album sales and fans, you can just see their decline." He wasn't exactly wrong -- Yield, which came out a year before Human Clay, went Platinum, while Binaural only managed Gold status -- but such dick-wagging hubris didn't exactly match the flavor profile of a band whose biggest record to date featured a song that made "Teach The Children" sound like "The Bad Touch" by comparison. "There is no excuse for the arrogance and stupidity," Stapp later stated in a post on the band's online bulletin board, under the pseudonym "Anthony Flippen"; just a few months later, Marshall was kicked out of the band, less due to his comments and more due to intra-band strain and his own struggles with alcohol addiction.

As with many rock acts that saw unbelievable commercial success around the turn of the millennium, it was more or less all downhill for Creed after Human Clay. Weathered ended up going 6x Platinum, just like My Own Prison, but the band broke up regardless in 2004, briefly reuniting for 2009's Full Circle and remaining inactive ever since. Stapp's since managed a solo career of his own, writing an awful theme song for the Florida Marlins and replacing late Stone Temple Pilots frontman Scott Weiland as the lead singer for post-grunge supergroup Art Of Anarchy; last year, the band sued Stapp for $1.2 million over an alleged failure to promote their most recent album, 2017's The Madness. All this career ephemera -- a maelstrom of low-level public embarrassment that so many post-grunge and nü-metal survivors have weathered in the last 15 years -- would suggest Human Clay is a footnote from the turn of the millennium with no real lasting impact.

And yet: The spirit of Human Clay -- and Creed at large -- has silently persisted through the last 20 years of rock and rock-adjacent radio. One of the greatest misnomers regarding Creed's thematic bent is that they were explicitly Christian in terms of belief systems, a commonly held assumption that Stapp (himself the son of a Pentecostal minister) had struck out against around the release of Human Clay: "A Christian band has an agenda to lead others to believe in their specific religious beliefs. We have no agenda!"

And that spiritual-but-not-religious approach courses through so much modern rock today, from the inspo-dystopia of Twenty One Pilots' airy, genre-fluid pop-rock to American Idol'er Chris Daughtry’s crunchy heartland-isms to Imagine Dragons' car-commercial uplift. We don’t have to wonder what something like Human Clay would sound like today, because it's already here, albeit with the guitars frequently swapped for synthesizers, drum machines, and rhythmic patterns ripped from modern-day hip-hop. The songs sound different, but underneath the new wardrobe, the arms remain wide open just the same.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]