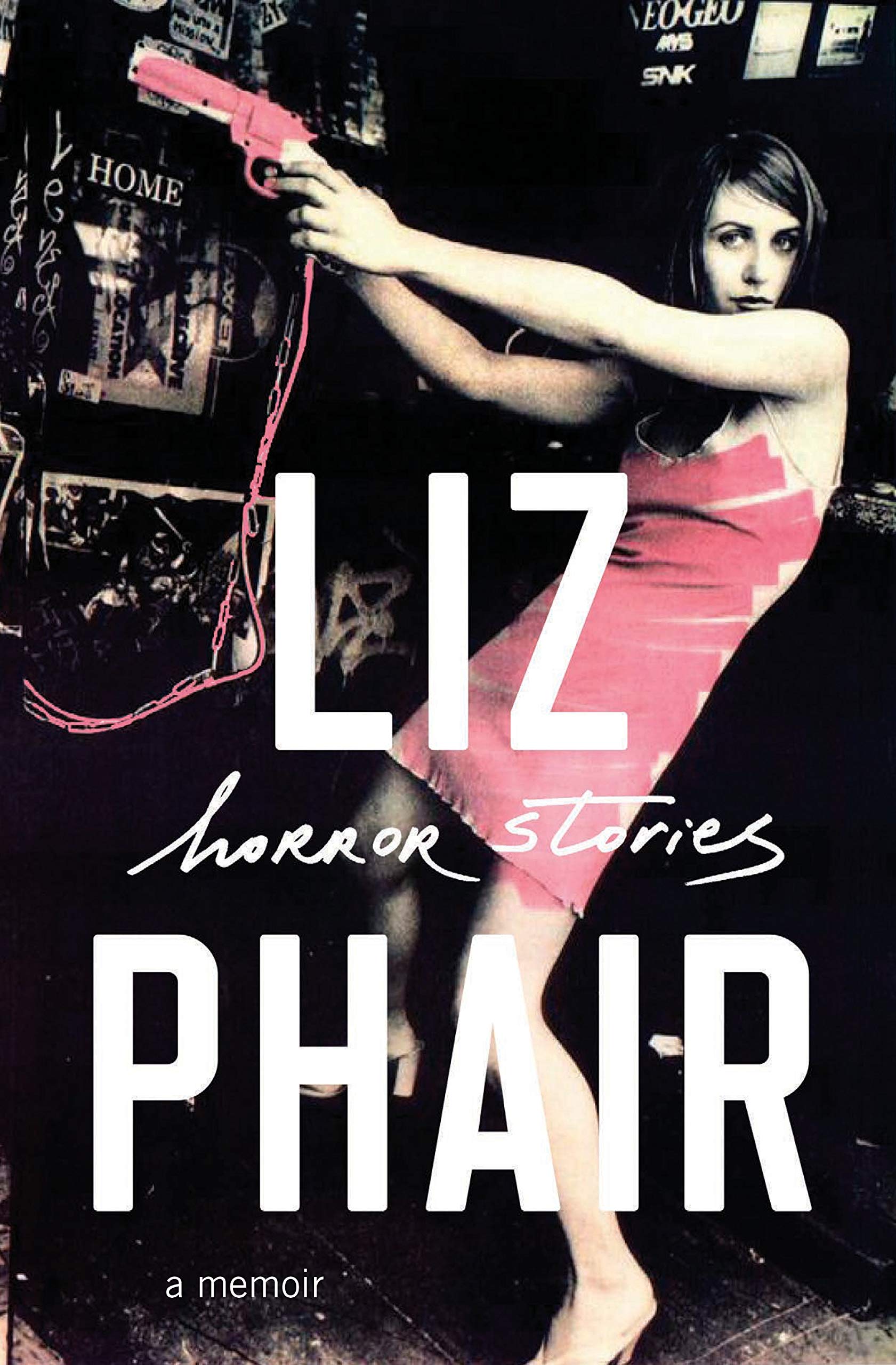

In the 26 years since she released her landmark debut Exile In Guyville, Liz Phair has been witness to just about every form of lunacy that the music business can offer. She’s been fetishized, demonized, worshipped, and scorned. Her music has changed a whole lot of lives for the better, and yet plenty of others spent years making a public sport out of dunking on her. It’s been a wild ride. In her new memoir Horror Stories, Phair tells us about some of the moments from that ride. We’ve pleased to present an exclusive excerpt from the book below.

I’m sitting in the makeup chair, one of those canvas-backed director’s thrones that are awkwardly tall and feel like they could fold inward at any moment. There’s too much air circulating around me -- on my calves and the small of my back, across my naked shoulder blades. I’m restless and anxious about the photo shoot, frustrated to be sidelined here in the beauty department while the rest of the crew discuss the setup. You’d never know it to look at me, though. I’m frozen in place, holding absolutely still.

A petite woman with red hair and perfect features is lining my lips. I have my mouth open in an obliging O shape, and she has her pencil in her hand, squinting at my vermilion border like a forensic scientist trying to trace the outline of a missing piece of evidence. We met fifteen minutes ago, and we are literally breathing into each other’s mouths. I try to conserve oxygen, exhaling slowly, off to one side. My eyes flick between hers, the pencil, and the large vanity mirror on the wall. I no longer recognize myself.

The incandescent globes give off a warm glow that is both comforting and vaguely incriminating. I feel X-rayed, displayed in flat white light with all my flaws magnified. The process of transformation is always the same, but the results vary considerably, depending on who the artist is and what look they’re going for. I never get used to the precision of professionally applied makeup on my already angular face. It seems like we’re doubling down where we should be compromising. But I let my glam squad do their thing, because the only outcome that matters is what the camera captures.

The pictures we’re taking today will run in a hip New York teen magazine, alongside a feature promoting my latest album. We’re down in the Meatpacking District at somebody’s friend’s loft, and the photographer is pregnant. It’s all very avant-garde, but I have to protect my upcoming record launch. I want to see the references for the concept they’re pitching. I need assurance that it’ll come across in print the way they say it will. I’ve been doing a lot of photo shoots lately, and I feel like my identity’s being robbed. I have no idea that I’m about to take some of the best pictures of my entire career.

When I first arrive at the loft space, they parade me around and introduce me to everyone on the team. We thumb through a rack of clothes as the photographer explains her vision. She wants to do something provocative, something that will push people’s buttons. I see a lot of bondage gear. If a man had suggested we explore S&M narratives, my hackles would have risen immediately. But the sight of this heavily pregnant woman directing a staff of eight while wearing combat boots, tight leather pants, and a concert T-shirt that barely covers her enormous belly completely disarms me, and I agree to go along with her inspiration.

What I’m itching to say now, as I sit here getting cosmetic powder pressed into my pores, is that I’ve changed my mind. I’ve had a few minutes to think about it, and I want to back out. I’m afraid the pictures will look tacky, or like porn, or -- worse -- like I’m desperately trying to convince people I’m still sexy. I call my manager again, but he’s halfway to midtown and not answering his phone. If I want to stop this train, I’ll have to speak to the conductor myself.

But there’s something else that’s preventing me. The makeup artist, whose face is hovering mere inches from my own, is crying. Not just weeping but sobbing uncontrollably. She doesn’t make a sound, but she’s obviously overcome. It’s a drama that’s unfolding between the two of us, since no one else has noticed anything. Each time she sniffs, her eyes clear temporarily. Then the tears well up and spill out again, running down her cheeks, along with what’s left of her mascara.

She’s also wet, soaked through from the rain that’s started pouring down outside. Somebody sent her out to buy cigarettes and tape from Duane Reade, and when she got back she was in pieces. She hasn’t even bothered to dry off. Whatever upset her is so grave that her own comfort is inconsequential. My first impression of her was positive. She was polished and friendly, an elfin Goth girl of twenty-two or twenty-three whose own makeup was immaculately applied and flattering to her complexion.

I can’t imagine what has happened to her in the interim. I wonder if her boyfriend called to break up with her, or if she bumped into an ex on the street. Maybe someone in her family died. I ask her if she’s all right, and she brushes off the question. “Yes, I’m fine.” If we were anywhere besides New York City, I’d press her further. But residents of this crowded metropolis have to construct a sense of privacy out of thin air and determination, and it’s not always nicer to pry.

The tip of her tiny nose is red. She’s working kohl pigment into my lash line, smudging it repeatedly with a beveled brush. She has to support one arm with the other, because her diaphragm is heaving, making her hand wobble. She doesn’t have time to take a break and calm down. I showed up late, and we’re behind schedule. Maybe I’ve caused her to miss an appointment, I think. But she seemed happy and relaxed before she went out.

I run through scenarios in my mind. Maybe she’s broke, and she just found out she lost a job that she was counting on. Maybe she’s recently sober, and it’s all become too much for her. Maybe her dog got hit by a car, but she can’t leave work, because she’s broke and recently sober. Conjecture is starting to scramble my brain like eggs. I have to focus on my own situation and figure out a way to salvage this photo shoot without sapping the inspiration from my photographer.

“You look amazing.” The hairstylist comes over and stands behind my chair, running his fingers through my shag. I glance in the mirror. I do look remarkable. The makeup artist has given me beautiful red lips and a bold, dark eye. The stylist continues to play with my hair, coaxing it up into a tousled, windswept texture until I feel wild and daring to match. The makeup artist smiles for the first time since her breakdown. I can tell she’s proud of her creation. I don’t want to disappoint any of them. I rotate my head from side to side, pulling expressions that I would never normally try, watching myself disappear inside a character.

And, just like that, we’re on the move. They rush me over to wardrobe, where I strip behind a flimsy curtain -- swapping my street clothes for the outfit they’ve selected. I’m so thin from all the work I’ve been doing that everything fits me like a glove. I emerge to gasps of delight. Despite my earlier qualms, even I get caught up in the fantasy. I’m a biker bitch. I’m Olivia Newton-John in Grease, after she turns bad at the end of the movie. I impulsively grab a red cowboy hat, and somebody lends me a cigarette. Now I’m Ponyboy from The Outsiders. It’s all a game of dress-up.

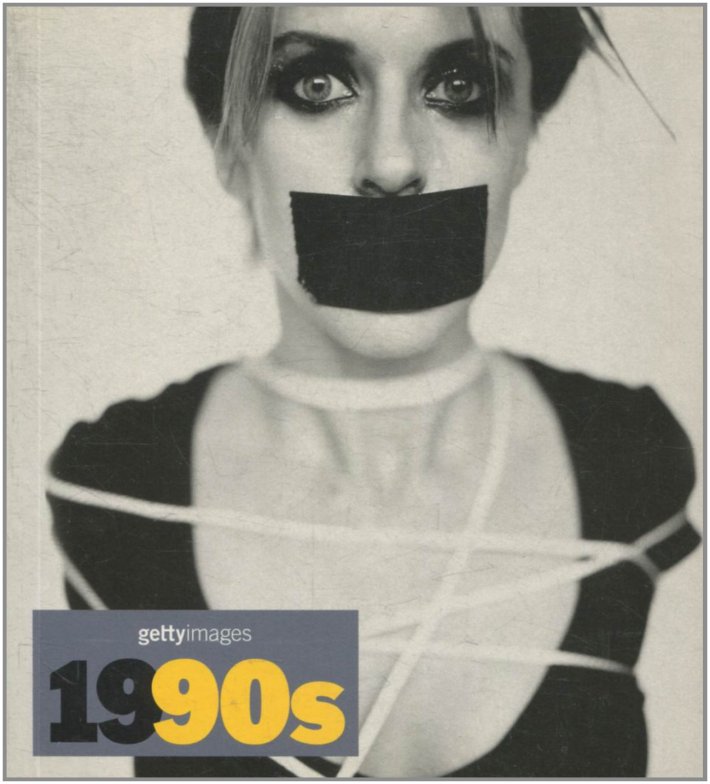

I step in front of the camera and strike saucy poses against the oilcloth backdrop. They’ve got good music playing, and we’re going wherever the moment takes us. The shots look incredible. Everybody leans over the photographer’s shoulder to admire her test prints. She lets me keep a few of the Polaroids. I feel uninhibited and free. But this journey has a destination, and the photographer has a road map for how to get us there. Each subsequent setup is more psychologically intense than the last, until we reach the boundary of my comfort zone. She wants me to make a bold statement about the subjugation of female power, to inhabit a role that makes me feel truly vulnerable. She wants me to embrace bondage. The hesitation in the room tells me that this fork in the road was anticipated. It’s up to me to say yes.

In the end, I do it for Magdalena. I put on a low-cut dress that accentuates my breasts. One of the assistants ties my arms behind my back, crisscrossing my body with a rope that he loops twice around my neck. My mouth is duct-taped. The only way I can communicate now is through my eyes. The makeup artist comes on set to smudge my eyeliner and administer glycerin drops to make it look like I’m crying. She stands in front of me, her cheeks dry as she makes mine wet. She’s had time to fix her own makeup, and she looks like a different person. She’s done a shimmery pastel look on herself, going for a completely different aesthetic.

That’s when it dawns on me that there was never any crisis. She got caught in the rain and her face came off; that’s all that happened. Her beauty-armor disintegrated, and without it she felt vulnerable and exposed -- naked in a way she hadn’t chosen to be. I pity her, thinking how sad it is for such a bright and talented girl to place so much stock in her appearance. Which is hilarious, considering that I’m working my good angles while trussed up like a glitter-basted chicken, wearing designer clothing under tungsten halogen lights, surrounded by a team of professionals hired to make sure I look stunning, and I’m still not convinced that it’ll turn out all right.

She inspects my makeup one last time, touching up any blemishes. Then she looks directly into my eyes, checking to see if I’m okay in here, inside this abduction-victim disguise. It catches me off guard, because I can tell she’s looking at me; not the recording artist who came in for a photo shoot, not the businesswoman who’s worried about her marketing, but the fragile, insecure person I think I’m fooling everybody into not noticing. “You look great,” she whispers. I nod, since I can’t speak, but I know that she’ll be there if I need her, if it all gets too much for me, if I can’t leave because I need this spread in the magazine -- along with a dozen other things that I rely on every day in order to feel in-control and safe.

We’re taking a risk by glamorizing suppression, but our gamble pays off. This shot of me bound and gagged will be chosen as the cover of the 1990s volume of Getty Images’ Decades of the Twentieth Century series, representing a whole wave of indie feminism. A strong female artist with a bold voice shown silenced and constrained. Only a woman could have taken this photograph, and maybe only a pregnant one would have conceived of it in the first place. In depicting the loss of freedom, the image calls attention to the bravery of the survivor. It’s the antithesis of my first album cover, in which my arms are flung apart, my mouth is open, I’m naked, natural, and lascivious. Oh, women are dolls! Let’s play with them.

By the time we’re done shooting, the rain has stopped. I get a round of applause, and everyone congratulates the photographer. It’s a wrap. The crew switches off the big studio lights, and the room is suddenly bathed in the lavender shadows of a stormy afternoon. The show’s over, the illusion undone. I step out of my borrowed clothes feeling a little let down, like Cinderella back to sweeping the floors after dancing all night at the ball. I wander out into the kitchen and marvel at how quickly I’ve gone from being the star attraction to being somebody no one pays any attention to. The grips are busy packing up their equipment. The makeup artist zips up her bags.

It feels weird to hang out, now that everything is back to normal. I want to leave, but my limo is stuck in traffic down by the Battery, and it’s rush hour, so I’ll never be able to catch a cab. The photographer is sharing her favorite shots of the day with her husband, the two of them huddled together in a touching pose of intimacy. They’re looking at pictures of me, but the girl in those photographs is someone else, someone who’ll never exist in quite the same way again; an amalgam of everyone who collaborated on the shoot. That’s the hardest part about being your own product: It’s difficult to know what’s you and what isn’t.

I decide to head out. I’m not sure where I’ll go, but I can walk around the block if I have to. As soon as I push open the big industrial door and step out into the freshly cleansed air, I feel a weight lift from me. It’s six o’clock, and the streets are jammed. Financiers in business suits and office workers in silk blouses crowd the sidewalk, moving rapidly, with single-minded purpose. Horns, sirens, and shouts punctuate the city soundtrack. I fall in step with the foot traffic, traveling east. I can feel people glancing at me as we pass one another. Though no one would mistake me for a model, I walk a little taller, with a little more swagger, exhilarated to have a secret occupation that makes me interesting. I stop in at a bodega to buy some health bars and a bottle of water. The man at the register can’t take his eyes off me. I smile demurely, counting my change, feeling as gamine as Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday.

As I’m leaving, I catch sight of myself in the mirror behind a display case. I look like a deranged zombie prostitute. My makeup, which was so striking in the photographs, is a frightening mess in natural daylight, caked on and settling into the creases. My eyeliner is smeared half an inch below my lashes. I’m horrified, the shame triggering old insecurities about my face.

When I was twelve, an age at which everyone else was starting to date, I had to wear glasses and braces. For a couple of years, I struggled with a persona that didn’t feel like my own. While other girls were moving ahead, I was stagnating. Once the braces came off and I got contacts, I wasted even more time trying to prove to myself that I was attractive. I’d pick out the hottest guy at a party and see if I could get him. We’d sneak off somewhere to fool around, but in the middle of it, I’d leave. Some of them called me a tease, but that wasn’t what I was doing. I was like a person suffering from OCD who keeps flipping on a light switch to make sure the electricity still works. And inside, I felt worse and worse. The mask I put on myself was far more distorting than a couple of pieces of metal and plastic.

That’s the thing they never tell you about looks. They matter; of course they do. But they weigh nothing compared to actions. You can change your looks easily if you have the right attitude, but bad patterns of behavior are like weeds: Once they take root, they are incredibly hard to eradicate.

I remember one photo shoot I did at the beginning of my career, maybe my first or second ever. Some newspaper in Chicago commissioned it and threw a party for themselves during the session. They laid me out on a fur carpet, wearing nothing but trousers and suspenders over my nipples, while anonymous guests -- strangers -- sipped cocktails and watched me from the periphery. It was disturbing, like the orgy scene in the film Eyes Wide Shut. I could hear the spectators commenting, but I couldn’t see them very well, because I was under bright lights while they were in the dim candlelit recesses of the studio.

Some of my lyrics are explicit, so I’m sure they expected me to dance around and be outrageous. But I couldn’t move. I just lay there, a photo-shoot virgin, dull eyed and mute. I was so freaked out that I retreated inside myself, disconnecting mentally from my surroundings. They were left with an empty shell of a person to work with. It was like bad sex. No one knew what to do about it. I didn’t know how to say no back then. I didn’t have a manager. I had no concept of what was normal for my profession.

The funny thing was, although I felt exploited and I hated it, it was the way my makeup looked that made me cry afterward. The makeup artist was the nicest, sweetest man, and my only ally in this upsetting situation, so I didn’t have the heart to tell him that his heavy bronzer, nude lips, and spidery fake eyelashes made me feel clownish and ashamed, like a dog wearing a cone collar or one of the last kids to be picked for a PE team. I kept thinking about how many people in the city were going to see me looking like this, and I was devastated.

What exactly are we evaluating when we think about our looks? Is it what’s actually there or how people respond to us that shapes our opinion of ourselves? Can you describe someone’s looks without picturing the way they move, the sound of their voice, or their personality? If you break it down into parts, just the physical attributes -- brown hair, brown eyes, round face, short, fat, pigeon-toed -- is that really how they look, or is it just shorthand for your much more nuanced and complex way of identifying them? Like skimming the title page and chapter names without reading the book. Even something as objective as a photograph shows the bias of whoever was holding the camera. And as a viewer, you add your own reaction to the image.

So what are looks? Seriously, what are they?

Liz Phair's memoir Horror Stories is out 10/8 via Random House.