On July 14, 2015, Nick Cave's teenage son Arthur died in a tragic accident, falling from a cliff in Brighton. The event, of course, irrevocably altered the path of Cave and his family's lives. It also, inevitably, will loom over whatever music he releases from now on. The story surrounded Skeleton Tree, his harrowing 2016 release with the Bad Seeds and the first new music he had unveiled since losing his son. But now Cave and his band have returned with Ghosteen, a sprawling double-album document of grief and despair and life continuing on, of grasping for some kind of relief, hope, or healing. Musically spacious and patient, thematically meditative as much as mythological, it is a quiet but titanic work.

People naturally thought Skeleton Tree was the album that represented Cave's raw, immediate reaction to Arthur's death. But in its accompanying Andrew Dominik-directed documentary, One More Time With Feeling, Cave and his wife Susie Bick actually talked of superstition, how in hindsight these songs seemed eerily prescient. That music was already in process when Arthur died; Cave has said he amended some lyrics, but despite Skeleton Tree being informed and reframed by Arthur's death, and despite One More Time With Feeling explicitly addressing the family's grief, neither project was solely in response to their tragedy.

Instead, Ghosteen is the first new album that began after Arthur's death, the one in which Cave is truly reckoning with that grief and its ramifications for him and the people he loves. Skeleton Tree was a deeply haunting album that at its end, colored by what had later occurred, strove to locate whatever possible resolution could be found in such circumstances. What we glimpsed in songs like "I Need You" and "Distant Sky" and "Skeleton Tree" is now expanded upon across Ghosteen's two halves. This is the aftermath, with all of its complicated angles.

Cave has dealt with his son's death in surprisingly public ways. He chose to let everyone into his family's mourning through One More Time With Feeling. He found a new level of connection with his audience, his openness met with people's own stories of loss. It prompted him to try an experiment, solo appearances in which he performed alone at the piano between taking questions from audience members over the course of two or three hours. This lined up with his online newsletter, the Red Hand Files. Once cagey and averse to the press, always enigmatic, this was a new version of Cave -- one who would answer people's functional questions about music, but would also casually wield some kind of measured wisdom when the conversation turned towards grief and family and love.

Not only was Cave letting people see his grieving process, it appeared that these changes became a part of that process itself -- strangers, connected by songs over the years, working this out together, for each other. So this is how Cave chose to announce the existence and impending arrival of Ghosteen, in a newsletter response that published just under two weeks before the album's release. No advance singles, no press, no traditional apparatuses. Just honoring that new communication with his listeners -- there is a new album, and we will all hear it together.

Even before you get to Ghosteen's obvious thematic weight, it's difficult to interact with the album in any vacuum, just on its own terms. Even knowing what we know about Skeleton Tree's inception, it was still perceived as the grief album; as a result, Ghosteen often plays like a response, an attempt to end a story that can't be ended. Cave knows this now: In the years before and since Arthur's death and Skeleton Tree, he's spoken about how he abandoned narrative songwriting and, on a broader level, lost faith in the notion of narratives in our lives. Instead, he's delved into the murkier waters and nonlinear directions of our experiences, images and allegories and snapshots both real and imagined flashing and colliding. Grief and love, resolve and defeat -- everything is interwoven across Ghosteen.

Stylistically, it does pick up threads from Skeleton Tree. Some of Ghosteen's songs seem to even directly echo or answer tracks from its predecessor. The ambient synths behind "Spinning Song" and "Night Raid" recall "Rings Of Saturn" or "Girl In Amber." The keening synth whine, once so effectively unsettling on "Jesus Alone," reappears in "Galleon Ship." Part of why they feel like conclusion, even as the stories they tell twist and fall and rise, is that they are more shades of blue, more melancholic twilight, but also even more achingly beautiful than his other recent work. There is a way in which they sound like the clouds parting after the corroded grey static, the abyss, of Skeleton Tree.

In a 2017 interview with The Guardian, Cave had mentioned he was writing again, and that he saw his output from this decade as a specifically linked body of work. He claimed his new material was not intended "to answer Skeleton Tree, but to artistically complete the trilogy of albums we began with Push The Sky Away." If you put his personal life to the side for a moment, you can still see an arc, a trilogy taking shape just as he intended. On Push The Sky Away, he had already found a more weathered sound through which he grappled with mortality, his favored themes beginning to feel more human and lived-in. Skeleton Tree was the bleak middle passage, a challenge to hold on to meaning in the face of how small we are.

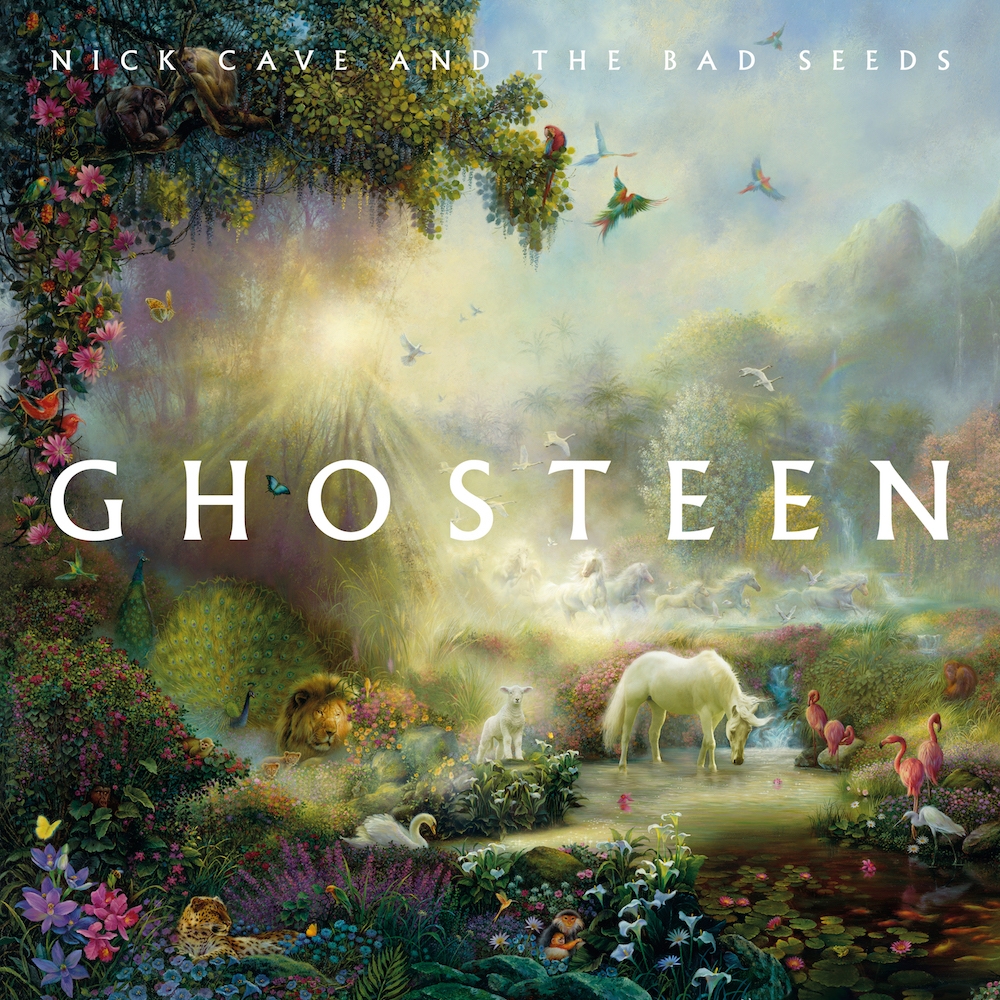

After those two albums, Ghosteen would almost sound like transcendence. This is the sound not of Nick Cave And The Bad Seeds pushing against the heavens or crash-landing in the attempt, but floating in the stratosphere themselves. There is little significant percussion or guitar or anything resembling rock music in general; this sound is the furthest extension of the diffuse and atypical structures hinted at on Push The Sky Away and aggressively fragmented on Skeleton Tree, and it's often brighter than anyone might have expected. There are somber piano ballads here, but mostly the album exists in this airy space, all of those soft synths holding Cave up as he intones from above, his voice bearing greater gravitas than ever. Throughout, he's answered by a chorus of backing vocals, like attempts at hymnal salves to wash away not only this album's suffering but the trials and searching of its two predecessors.

Purely in terms of Cave's body of work, Ghosteen is another major achievement in one of the most remarkable late-career stretches anyone's ever had. Though there's been no significant or sustained downturn in his career, with his masterpieces spread evenly throughout the years, there was a sense that he'd locked into a new level of inspiration with Push The Sky Away and Skeleton Tree. Now, with Ghosteen completing this decade's trilogy, it's hard to go back and hear his old material, even at its best, without thinking of this aging version of Cave, this far-seeing and battered poet, as the best version of him as an artist. As a writer, he is concluding this decade at the height of his powers.

But it feels beyond reductive to approach Ghosteen as simply a career milestone in a musician's life. Like Skeleton Tree, how do you really rank this against another album in the same year? From a critical standpoint, you're supposed to be able to brush aside context and assess the music on its own terms. That just doesn't feel possible with Ghosteen. This isn't just an impressive and adventurous collection of songwriting from an aging icon. Continuing from Skeleton Tree and Cave's growing openness, it feels like the transformation he promised on "Jubilee Street" back in 2013. This is an artist giving us all of themselves, an artist creating a work that seeks to make sense of life's biggest questions and worst struggles, in ways both deeply personal and universally empathetic.

Nick Cave was never a stranger to death, but his recent albums are far removed from the outlaws and violence and hedonism of his earlier years. Naturally, Ghosteen is an album about loss, but it is also an album about connections between human beings, and about how those left behind pick up and repair their lives, to whatever extent that's even possible. It depicts those who remain, and the solace we might still try and find in one another.

Just as Ghosteen exists in conversation with Cave's recent work, it exists in conversation with itself. There are recurring themes and images throughout. On songs like "Waiting For You" or "Bright Horses," Cave is waiting for people to return -- in the latter, it's his partner, coming home on the train, but just as often it conjures that sense where, after someone's gone, you can temporarily forget that reality. You keep expecting their name to reappear on your phone's screen, to see them walk through a door; you see their face on strangers on the street.

There are repeated reassurances of "I'm beside you," most often seeming to communicate with his wife, or his other children, to let everyone know we're still here and we're still together through this. On "Ghosteen Speaks," the meaning flips: It sounds as if this time, it's Arthur sending a transmission to his father, letting him know he's still with him in some form.

This isn't the only time when the repeated phrases or ideas shift, or conflict with each other. On the album opener "Spinning Song," Cave concludes by promising that "Peace will come in time/ A time will come for us." At that moment, it seems like he's reaching for the belief that life can continue on. By the end of "Hollywood," the closer of Ghosteen's second half and thus the conclusion to the whole album, he sings, "And I'm just waiting now for my time to come/ I'm just waiting now for peace to come." This time, it sounds as if he's waiting until he is set free, too, no longer having to walk around tormented by memories of losing a child. In several songs, he talks of children ascending to the sky, disappearing to the sun or moon.

All of this is communicated by imagery both small and personal -- smoking on the bed, sitting in the carpark, washing clothes -- mixed with cosmic-level ruminating on our existence. Jesus -- the miracle birth, but also the son who died -- appears frequently, even by Cave's standards for Biblical reference. The entire album opens with what initially appears a non-sequitur into one of Cave's old favored topics, the faded and seedy endgame of Americana iconography: a king of rock 'n' roll in Vegas, depleted and towards the end of his life and reign. But then this turns into a parable, about the ripple effects we leave when we're gone. You could take it as Cave musing on work, what he might leave to the world, or contemplating how people still linger with us in the ether.

Perhaps the most crushing passage on either half of the album is the old Buddhist tale of Kisa Gotami. Cave relates it in full -- her child has died, she seeks the counsel of the Buddha, who tells her to collect mustard seeds from each house where nobody has died, and in the end she realizes no house is safe from death and begins her path toward enlightenment. “Everybody's losing someone/ It's a long way to find peace of mind,” he concludes. It's one of several unexpected moments on Ghosteen in which Cave pushes his voice to higher registers than in the past, making himself sound more broken and vulnerable than ever before.

In what little information Cave has offered about the album thus far, he has called the songs on the first album the "children" and the songs on the second "their parents." This is almost an inversion of what you might expect. The long, wandering stretches of Ghosteen's second act are more obviously tortured, trying to sort through things and mostly failing. On the first half, there's a greater sense of acceptance, of wisdom -- almost an enlightened innocence. It's telling that he draws these lines, suggesting the older ones carry this weight where there could be some potential, some notion of future, located in our children. The fact that you could even interpret Ghosteen's halves this way speaks to the album's surprising capability to find some version of tranquility in the wake of catastrophic trauma.

In the same description, he called Ghosteen a "migrating spirit." Moving between songs, across albums, the symbol ties together the moments of opposition at different ends of Ghosteen. But on the second album, its presence makes for a particularly devastating piece of art. If Cave had just released that second half, it would still register as a monumental work. "Ghosteen" and "Hollywood" are both among the most heartbreaking, transfixing songs he's ever written, each somehow feeling like stream of consciousness -- a lost man yearning for answers or release, in real time -- at the same time they feel like intricate multi-part suites tracing the corners of grief and what comes next.

In "Ghosteen," the titular character dances in Cave's head, pushing him through this spiral. Eventually, he offers, "There's nothing wrong with loving something/ You can't hold in your hand." The Buddhist tale in "Hollywood" is such a resounding epilogue partially because of the preceding images. Cave escaping to the West Coast, looking towards the lure and fantasies that once animated him, to the place that always promised new beginnings -- only, again, to be answered by an ancient reminder that none of us can escape this.

Sitting between the two is "Fireflies," a spoken-word interlude that is also, essentially, the core meaning of the album, the thesis around which those two songs extend and around which the whole album swirls. Cave depicts our existence in simple terms simultaneously banal and celestial -- we are pieces of matter in this great unexplainable system, star remnants. "I am here and you are where you are," he says, apparently speaking to Arthur. It's one more moment of acceptance, of making sense of this through acknowledging an order we can't comprehend, surrounded by turmoil.

For all its subtle wonder, Ghosteen is not an easy album to listen to. Even Skeleton Tree, sitting in a career full of dark albums, seemed easier to return to. As giving as Ghosteen might be, it is also demanding. With all of its different passages, it sketches out little pieces of the stages of grief. It is incredibly heavy, more so than Skeleton Tree -- which, despite not even being about Arthur's death, seemed more exclusively about loss and the immediate retreat towards the loves still here.

Ghosteen moves well beyond that, arising from personal circumstances but expanding into questions of what we do with our lives, who are we to the people who care about us, who they are to us. When Cave sings "Everyone's losing somebody," he is opening a way in, making this album resonate even for those of us who never lost a child, or who never had a child. But at the same time, that asks something of us, for us to listen and wrangle our own thoughts about existence, and the things we gain and lose along the way.

The first time I listened to Ghosteen, I was driving down a desolate highway in northern Ohio just as the final moments of daytime were totally swallowed up. My headlights hit nothing, just empty endless asphalt. No signs of life. There was an engulfing sense of aloneness, even though there were other people in the car with me -- the sense that, as the album overtook us, we were one small speck moving through nothingness with only a hope, or delusion, that the end destination would mean anything. Hearing all of this at once for the first time without any preconceived notion of what the album might sound like, feeling the gravitational force of those elusive synths and of past generations ground into the gravel of Cave's voice, the outside world receded from focus. Hurtling into an impenetrable night, all I could think about was everyone I had ever known, the ones who are gone and the ones who are still here alike. I very much wanted to see them all again.