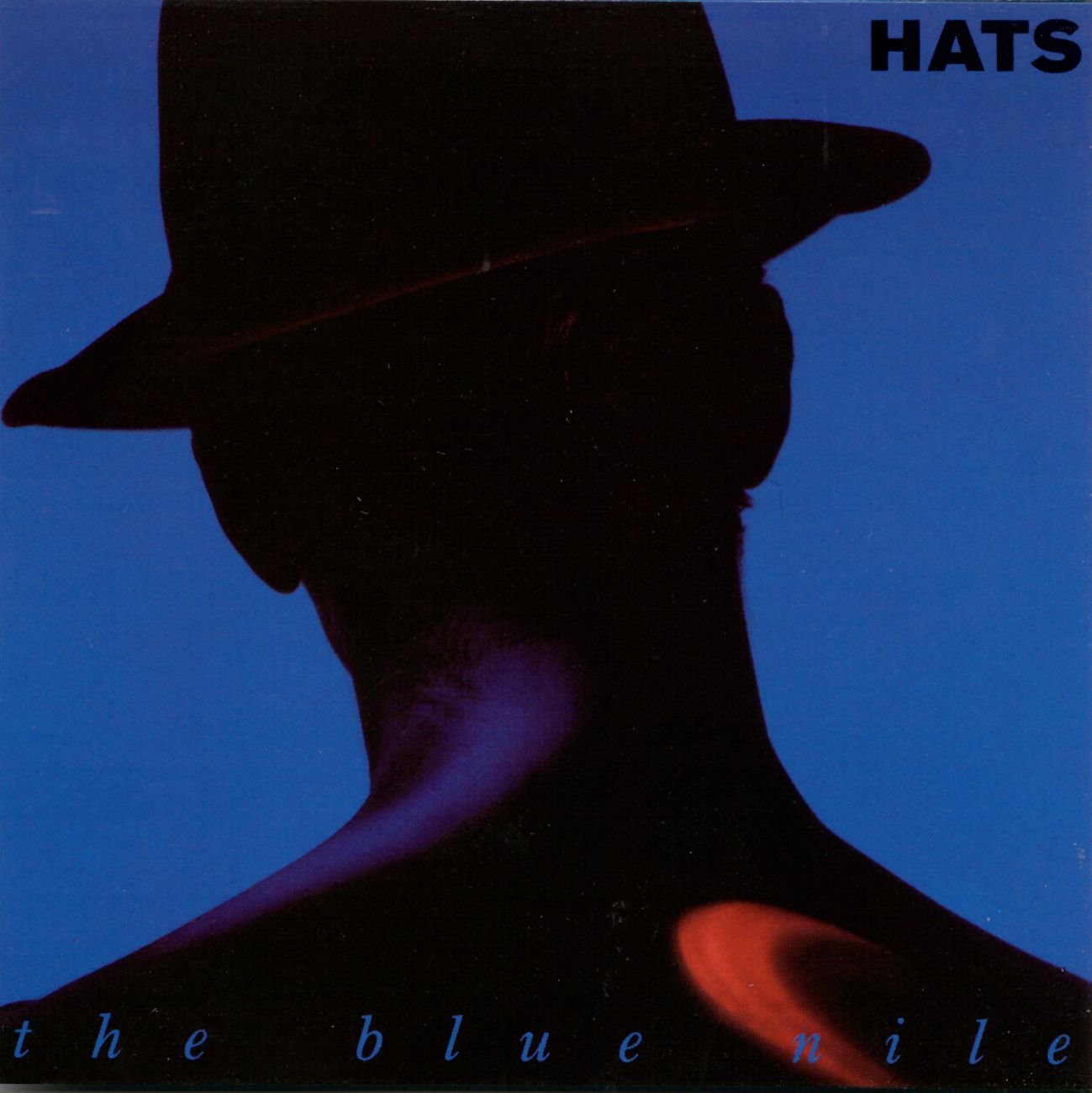

Some albums are just mysteries. They have their time and place, and yet resist their context. They are slow to unfold and get their due, and yet grow beyond their original confines as a result, spanning generations and building pockets of devotees. Ultimately they become known but still hidden, gems waiting to be unearthed again. These are the terms we usually ascribe to a "cult classic," a masterpiece that occurred on the sidelines, never defining a moment in music history but steadily permeating the atmosphere until their stature overshadows not only any missed chance at mainstream dominance but the basic concepts of the music business and how bands are supposed to act and exist. Thirty years ago this week, the Blue Nile released one of those albums. They called it, of all things, Hats.

The story about Hats, and the Blue Nile in general, is uncustomary, though it began normally enough: While attending the University Of Glasgow, Paul Buchanan, PJ Moore, and Robert Bell tried to start a couple different bands, none of which took. Eventually, they became the Blue Nile and, this being the punk era, set about trying to make music with the rudimentary gear and means they had at their disposal. In a roundabout way -- through their engineer Calum Malcolm -- they caught the ear of a hi-fi audio equipment company called Linn Products, which was in the process of starting a record label. Their debut, 1984's A Walk Across The Rooftops, was the first release on Linn Records.

Critics loved A Walk Across The Rooftops, and for good reason. It still, even after all these years of historical framework settling into place, doesn't sound quite like anything else from the time. Yes, there are strains of synth-pop and signals of what would later become known as sophisti-pop, but the Blue Nile were tapped into something else. Their album was urbane and poetic, yet not derived from the same post-industrial dystopian visions as early '80s new wave.

The band would argue there was a punk quality to it -- they barely knew how to play their instruments, the drum machine was out of necessity -- and yet they produced an album that was deeply romantic and ethereal, whether in surges like "Tinseltown In The Rain" and "Stay" or in tracks like "From Rags To Riches," which was almost synth psychedelia as concocted in a snow-covered northern European town. They had carved out their own sound from the start, and though it wasn't always immediate, the hooks and emotion were there. They could just keep getting bigger.

It wouldn't be the first (and certainly not the last) time, but the Blue Nile took a different path. The follow-up to A Walk Across The Rooftops took a full five and a half years to materialize. In the interim, the band tried to make another album and, unsatisfied with its direction, scrapped and destroyed a bunch of partially-finished material. But when they began again, it all came together more quickly. It all made more sense. Somehow, again, something sublime flowed through this group of musicians who didn't always seem to know what they were doing. The result was Hats.

Even in an era in which every chapter of the past feels thoroughly exhumed and reexamined for new inspiration, even when the '80s specifically seem to have been completely mined, Hats remains a curiosity, a deep cut, almost a piece of word-of-mouth folklore. The Blue Nile's music is patient in its arrival -- from 1984 to 2004, they released just four albums -- and patient in character. You need to sit with their songs, sink into them.

[photoembed id="2061725" size="full_width" alignment="center" text=""]

Despite recurring spikes of interest and occasional attempts at exposing more listeners to the catalog -- expanded remasters of their albums appeared earlier this decade, and new vinyl reissues were recently announced -- there is something about the Blue Nile that makes them feel as if they will always be a secret buried in time. They're the sort of transfixing and elusive artist where, when you first discover them, you will alternate between telling everyone you've ever known about them with the fervor of an evangelist, and retreating to protect this precious thing you have found. There's a way in which their music can very much feel like its your own, not to be shared with anyone. That you can only discuss it with the sort of hushed awe from which it seems to be born.

Of course, there have been plenty of people who did come across the Blue Nile over the years, who adored them from the start. Many of them were fellow musicians. In their earlier days, they received shoutouts from Phil Collins and Peter Gabriel. Years later, Buchanan would work with Gabriel on 2000's OVO. It's not the only instance of one of their contemporaries or predecessors finding something vital in their music; artists like Annie Lennox and Rod Stewart have covered them. (Both sang "The Downtown Lights," a highlight from Hats and from the band's career overall.)

In more recent years, their name seems to keep reappearing -- maybe not more frequently, exactly, but perhaps a new generation is finding them. Or, as impossible as it seems for anyone to sound like the Blue Nile, maybe their influence is more significant this time around. Artists with as much history as Destroyer and as freshly exciting as Westerman have been compared to them. The 1975's Matty Healy has talked about listening to Hats constantly while crafting last year's A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships; this year, Natasha Khan, an artist obviously well-versed in the '80s, mentioned discovering them for the first time while working on the new Bat For Lashes album Lost Girls. Pure Bathing Culture covered the entirety of Hats last year; they were joined by Ben Gibbard on a couple songs. A couple months later, fellow Scots Chvrches offered their own rendition of "The Downtown Lights." And Buchanan still reemerges as a co-writer from time to time, most recently on Jessie Ware's Glasshouse in 2017.

The Blue Nile ❤❤❤

— Jessie Ware (@JessieWare) September 30, 2012

Clearly, other artists responded to the subtlety and ingenuity of the Blue Nile's music. But, still, it's strange to find people coming back to a band so quiet and hermetic, for the Blue Nile to be getting some new kind of reverence, decades later. The reason -- more so than the strength of A Walk Across The Rooftops, more so than their more divisive later releases -- is Hats. Existential and prematurely wizened, Hats is the kind of lost classic that continues to yield new revelations every time you listen to it, even 30 years on.

Both specific and diffuse, Hats is built on concrete images strung together into an impressionistic portrait of the city, and what life there must be like, and how banal and grandiose our romances and day-to-day existences might become. It is restrained music, the slow-rising reveal of a car cresting a hill and a skyline coming into view for the first time, or late night ambles leading to unknown corners of town, all of this occurring in a headspace that feels like opening and closing credits at once.

At only seven tracks, Hats still feels like a monumental listen full of contradictions, of conflicting ideas and potential outcomes. It is a spare album, yet lush. Its songs are slow and atmospheric, yet drenched in glimmering synths and wielding the periodic dramatic flourish. Buchanan's soulful voice often hangs low in meditation or mourning, then will burst into moments of anguish or fleeting grasps at joy. In under 40 minutes, the Blue Nile create a world all their own, one that reflects visions of ours; in under 40 minutes, they use snapshots to trace a spectrum of human experience, deploying all of those nocturnal synths and heartbroken melodies to depict the connective tissue between our most elated highs and our most forlorn lows.

Often called "noirish," Hats is indeed the sound of cities at night. In its synths you can hear streetlights rendered as watery embers in the reflections of rain-slicked asphalt. In Buchanan's vocals, you can hear a million nameless characters smoking in the corner of decrepit bars, lit by aged neon, and you can picture all of those people and all of their lives and how they pass by your own without ever touching. In many ways, the album feels like it takes place in a city that was never quite real aside from in films, or a city we construct and populate in our heads when viewed from the distance of stray photographs. A city of more allure and rebirth, but also more brutal defeat and sadness, than actually ever exists. Regardless, it is a vivid setting, established in small pieces and images yet with enough colors that you can easily imagine someone -- Buchanan, a narrator, yourself -- experiencing all of these things in this place.

In some ways, you can almost hear Hats as taking place in one 24-hour period, a final struggle to salvage a depleted relationship under the beacons of skyscrapers giving way to a dark night of the soul. "Over The Hillside" is the approach, a prelude that strives to locate rejuvenation on the horizon, that old iconography of that something else at the other end of the journey. "The Downtown Lights" is the welcoming fanfare, the poppier single that makes you feel embraced by the city, full of anticipation as much as broken fragments.

From there, the fault lines make themselves more obviously known. At best, "Let's Go Out Tonight" is the strung-out manifesto for a self-destructive couple; more likely, it's a desperate plea to give everything one more shot, that one more night might relocate some sense of wonder. "Headlights On The Parade," like "The Downtown Lights," is the catchier side of Hats -- and unlike most of the album, it's where you could be lured into a sense of euphoria, as if it's the moment where that wonder actually was recalled or reclaimed, that moment in a night out when you can temporarily fool yourself into thinking anything's possible.

It's answered by "From A Late Night Train" -- a particularly sparse song, just Buchanan and piano and a distant, ghostly trumpet, all a bleary-eyed exhale watching other people carry on with their lives -- and "Seven A.M.," a drunken, depressed reckoning with the sunrise with nothing to show for it but more desolation. After it all, the cycle begins again with "Saturday Night" -- a world-weary dream of a way to start over, new love on another new night.

At the same time, Hats is nothing approaching a story-driven concept album. You could read an arc onto it, or you could hear it as all of your nights out and all of your failed relationships collecting into one watercolor memory. The album elides time like that, fading into view and then disappearing back into the ether. It plays like a sensory recollection of every defeat and victory alike.

Much of this is thanks to Buchanan's lyrical approach across the album. He uses repeated signifiers -- the streets and bars both empty and crowded, the night, city lights, cigarettes and neon -- that are on some level empty placholders but collectively become this evocative tapestry of that one city, that one night, that you might need it to be, or of all the suggested ones you want to inhabit. Like many great albums that feel as if they are engulfing you at the same time they are unreachable, you can write yourself into Hats as much as you can take it as a bare, personal missive from Buchanan.

Make no mistake -- you can hear a lot of Buchanan's own pain and searching in this album. As suggestive as Hats is, it is also strikingly idiosyncratic, all of those vignettes clearly felt on a visceral level by the people who are performing them. Considering how the Blue Nile's career proceeded from here, it doesn't necessarily feel as if there's resolution here, even in the twinkling denouement of "Saturday Night." But that's never what the album has felt it should be about. Rather, it's a trio of musicians breathing in the night, letting all of this baggage loose into it, and seeing if it all mingles together, if something could change, just maybe. For each paean to a withering love, Burchanan circles back around to reassurances, to himself as much as us: "It's all right" in "The Downtown Lights," "I love an ordinary girl/ She'll make the world all right" in "Saturday Night."

Part of the reason Hats has drawn so many people in, part of why it still feels so enigmatic, is that it exists in liminal spaces. It is between swells of love and relationships crumbling, it is between the weathered final strains of one night and the fresh start of another. It is between genres, it is between eras. It is between the realities of our surroundings and the dreams we project onto them. If you have spent any time traversing a city at night while listening to Hats, you know it's the sound of being out amongst all of this apparent opportunity, but still feeling isolated and listless within all of it. It's the sound of living some years, and wandering familiar streets as if they'll finally provide an unexpected answer. In the face of all this theoretical newness, you instead can't shake the feeling of loss, the feeling that there should've been something more, the feeling of time having passed, the feeling that you will never stop searching for something you can't actually hold.

All these years later, it remains a singular work, and also a singular work within the Blue Nile's own career. From there, the yawning gaps between releases would widen even further; it would be seven years until Peace At Last arrived in 1996, and another eight until High in 2004. Though it was talked around at the time of High's release, by the early '10s -- when Buchanan was promoting his 2012 solo album Mid-Air -- it became clear that the Blue Nile weren't just waiting an even longer stretch until a new collection, but that they had ceased functioning as a band.

Hats would never be repeated, and not just because of the practicalities of there being over half a decade between it and its successor. By the time the Blue Nile returned, their influence had manifested in '90s adult-contemporary (remember the Rod Stewart cover?), and they started to sound like that, too. By the time Buchanan released Mid-Air, he had pared down his music even further, into naked piano-and-voice song sketches. Hats wasn't the result of five years of megalomaniacal studio tinkering perfectionism. It was what struck them in that moment, and whatever passed through them later took a different form.

The Blue Nile's career defies narrative. Like the music, the story itself is all ellipses. Yet as much as they favored gestures and leaving things not-totally-said, their albums remain complete ideas. These albums might not entirely reveal themselves, but they are there, waiting, for you to find your own meaning in them. With Hats in particular, the thing they left behind is pristine yet worn, a crystal covered in grime and tears but still shining through.

Maybe that's what keeps us coming back. Hats can be a sad album that helps you through your own trials, but ultimately it feels like one of those albums that's almost haunted by the beauty that could be right there in front of us. An album of loneliness, it's the sound of drifting through one cityscape after another, in one more anonymous car, dreaming of ever more entrancing skylines even as the world's most stunning and glittering ones already surround you. It compels you to remember life lived and to imagine all the others left unsaid, but can make you feel your own history as vibrantly as the world it creates. This is what makes an album as seemingly simple and contained as Hats so expansive and enduring. This is the end of things -- at least, some things. But at the corner of every note, you can still hear the faint hint of hope and possibility, of new nights opening up to make you ask what could happen next.