In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

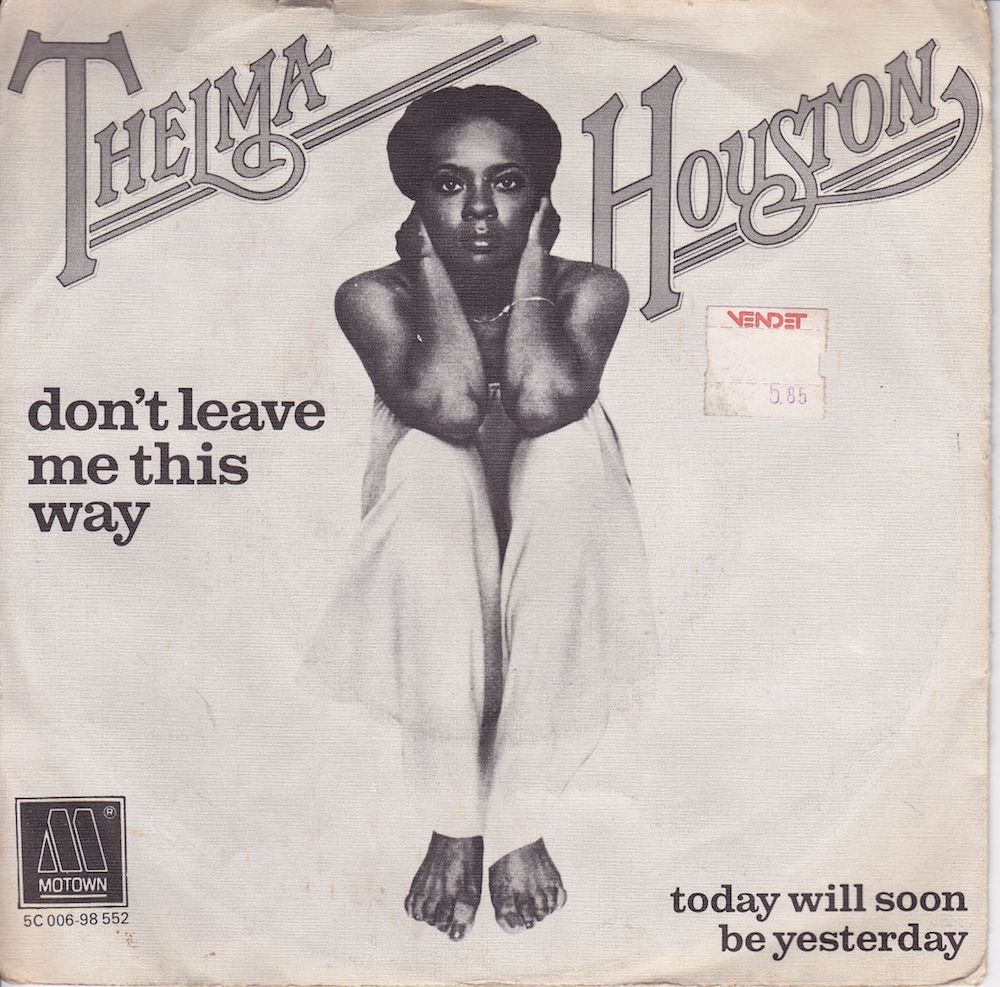

Thelma Houston - "Don't Leave Me This Way"

HIT #1: April 23, 1977

STAYED AT #1: 1 week

There is absolutely nothing in this world like what happens when disco music is operating at peak capacity. Disco was a wave that swept all across pop music for years. It was tremendous, all-encompassing, and, when done wrong, flattening. The whole genre was more or less built around a drum pattern -- a stead thump-thump-thump kick -- that kept people in clubs moving and made it easy for DJs to blend one song into the next. If that beat was all you were hearing on pop radio, I could see how it could get oppressive. And in some of the disco records of the time, you can hear a certain inertia -- artists and producers and songwriters feeling limited by making sure their songs fit a particular mold.

But when that mold worked? Holy shit. A truly great disco song turned religious ecstasy into something physical and tangible, something you could grasp. It spoke to the idea that we could achieve some kind of transcendence ourselves, together, on a dancefloor. I'll never know what it was like to hear those songs when they were new, blasted loud in rooms full of spinning lights and sweat-slick polyester. But in the best of those songs, I can hear the charge in the air, however long ago that charge might've dissipated.

There were people who became stars because of disco, and there were fading stars who used disco to extend or even elevate their fame. But disco, like early rock 'n' roll, was also a genre of fast, elusive, one-time success. Every once in a while, when everything lined up just right, a long-toiling artist could hit just the right sound at just the right moment and make something immortal. That's what happened when Thelma Houston made "Don't Leave Me This Way."

Most of Thelma Houston's career works as a story of what happens when the starmaking machine fails. Houston -- no relation to Whitney or her extended clan -- was an absolute monster of a singer, one who was capable of taking her gospel training and using it to make earthly concerns sound urgent and wracked and overwhelmingly joyous. She spent years with Motown, a label that should've known exactly what to do with a singer of her surpassing power. But for Thelma Houston, everything clicked exactly once. Thankfully, that one time was something special.

Houston, born in Mississippi and mostly raised in the LA suburb of Long Beach, was already married and divorced, with two kids, by the time she even attempted to make a career out of music. She'd been singing with a local gospel group and occasionally touring when the Fifth Dimension's manager Marc Gordon heard her in a nightclub and signed her to Dunhill Records. Jimmy Webb, the songwriter famous for his work with Glen Campbell, wrote and produced Sunshower, Houston's 1969 debut album. (A Jimmy Webb song will soon appear in this column.) But the album didn't sell, and Houston moved over to Motown a couple of years later.

Houston became part of MoWest, a Motown subsidiary, and her early singles for the label didn't chart. So Motown kept her on the backburner. She sang backup vocals or did songs for soundtracks. She sang in nightclubs. She spent a year in the cast of a sketch-comedy show called The Marty Feldman Comedy Machine. She recorded a 1975 album for another label, with a band called the Pressure Cooker. She recorded the original version of "Do You Know Where You're Going To" before Berry Gordy decided to give the song to Diana Ross instead, making it the theme for Ross' movie Mahogany. Thelma Houston was going nowhere. But then "Don't Leave Me This Way" happened.

"Don't Leave Me This Way" was more than a year old by the time Houston got to it. Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff wrote the song with the Philadelphia International lyricist Cary Gilbert, and Gamble/Huff mainstays Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes recorded the song for their 1975 album Wake Up Everybody. In the Blue Notes' hands, "Don't Leave Me This Way" is warm, itchy Philly soul, with sweeping strings and triumphant horns. The song leans disco, but it never fully gives in, even though it stretches over a luxurious six minutes. Teddy Pendergrass sings it with a deep ache in his voice, gritting his way through it like he's trying to will a relationship back to life. (Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes' highest-charting single, 1972's "If You Don't Know Me By Now," peaked at #3. It's a 7.)

In the UK, the Blue Notes' version of "Don't Leave Me This Way" was a hit, peaking at #5. But in the US, Philadelphia International never released the song as a single. It got play in clubs, reaching #3 on Billboard's disco chart, but it never made the Hot 100. One night, though, Hal Davis, the Motown producer behind the Jackson 5's "I'll Be There" and Diana Ross' "Love Hangover," heard "Don't Leave Me This Way" at a party. Davis was working on Houston's Any Way You Like It album, and he turned "Don't Leave Me This Way" into an absolute banger for her.

In its original form, "Don't Leave Me This Way" was a great song. But the Thelma Houston version is so much better that it immediately turned the original into an afterthought. Houston and Davis made a masterpiece out of the song. Their version of it follows the same basic format as what Davis did with "Love Hangover," except that the aqueous intro only lasts about 20 seconds before the drums kick in. Even without that one dramatic song-switch moment, "Don't Leave Me This Way" builds drama and intensity throughout. It never settles down.

The Motown of 1976 wasn't what it had been a decade earlier. The old studio-musician geniuses were working for other labels. So were many of the best songwriters. The base of operations had moved to Los Angeles. And yet "Don't Leave Me This Way" stands as proof that the old assembly-line craftsmanship was still there. Listen to the way "Don't Leave Me This Way" just keeps twisting and wriggling. Listen to the bridge, when the bass and clavinet and tambourine find some new fissure in the groove and just start talking to each other. Listen to the way the horns come roaring in during the final minute. Listen to the way the strings gradually fade into oblivion, letting the beat take over. The track is an absolute marvel of design.

As for Houston, it can't be easy to out-sing Teddy Pendergrass on his own tune, but she does it. "Don't Leave Me This Way" is a deeply horny song, at least in the way Houston sings it. On paper, it might be a breakup song -- "don't leave me" -- but it's clearly more about physical need, about longing for someone's touch. Houston has to sell both interpretations of the song, and she does it by channeling all her gospel firepower, transforming the song into an anthem of raw and convulsive want: "My heart is full of love and desire for you! So come on down and do what you've got to do! You started this fire down in my soul! Now can't you see it's burning out of control!"

A lot of the best disco songs are basically showtunes. They take everyday love-life situations and blow them into theatrical showstoppers, building up drama with each passing moment. That's what Houston does with "Don't Leave Me This Way." She starts out with a wordless sigh. As the beat drops, she's keeping herself contained, but just barely. As soon as she hits the chorus, though, she explodes. The buildup to that chorus -- "awwww, baby! -- is a minor pop-music miracle just in itself.

Throughout the song, Houston explodes again and again. By the time the song ends, she's almost panting: "Satisfy! The need in me!" But she still builds everything up to one long glorious, stretched-out showcase note, the kind of thing where people break into applause mid-song before the note is even over.

Houston sells "Don't Leave Me This Way" by making her own horniness sound apocalyptically important -- like she believes her entire life depends on this person coming back and taking care of this situation. Because the Blue Notes' original has no gendered pronouns -- it's only directed to "you" -- Houston doesn't have to change a word. Maybe that's helped the song maintain its status as a gay anthem for the past four decades. Or maybe it's just that it's an absolutely fucking great disco song.

(Also, "Don't Leave Me This Way" was the #1 song in America when my wife was born. So that's another thing I like about it.)

"Don't Leave Me This Way" is a perfect song that hit at the perfect moment, and Houston never came close to it again. Most of her later singles didn't chart. Her biggest hit after "Don't Leave Me This Way," 1979's buoyant "Saturday Night, Sunday Morning," topped out at #34. In the '80s, she left Motown and recorded another album with Jimmy Webb, but that one didn't sell, either. In the '90s, she joined Sisters Of Glory, a gospel supergroup that also included people like CeCe Peniston and Phoebe Snow, and they played Woodstock '94 and did a show in Rome for Pope John Paul II. Houston is still around, still playing the nostalgia circuit. And really, it doesn't matter that she never did anything else as powerful as "Don't Leave Me This Way." Most of us will never do anything as powerful as "Don't Leave Me This Way."

GRADE: 10/10

BONUS BEATS: The Communards, the former Bronski Beat frontman Jimmy Somerville's dance-pop group, released a synthed-out cover of "Don't Leave Me This Way" in 1986. Their version of the song only made it to #40 in the US, but in the UK, it went to #1 for four weeks. Here's the video:

BONUS BONUS BEATS: RZA sampled Thelma Houston's drawn-out sigh from the "Don't Leave Me This Way" intro on "Labels," a deep cut from his cousin the GZA's 1995 classic Liquid Swords. Here's that song: