They've been showing up again in my social-media feed lately: Fiona Apple and Paul Thomas Anderson at the Out Of Sight premiere in 1998. There's a context for all this, of course. In the great recent stripper caper Hustlers, Jennifer Lopez makes a grand entrance while dancing to Apple's song "Criminal." And in a recent Vulture interview, Apple mentions that she was in the same room as Lopez once -- that Out Of Sight premiere. Anyway, the photos are incredible. Apple and Anderson look absurd. Anderson has on a bucket hat, Spud-from-Trainspotting sunglasses, sweatpants, and flip-flops. His shirt is way more open than it should be. Apple has a crop top and, like, low-rise Hammerpants. This wasn't laundry day; it was a movie premiere. But in 1998, you could show up to a movie premiere looking like you'd just rolled out of bed, as long as people knew you were brilliant.

Not everyone knew Fiona Apple was brilliant. This was a sticking point. Thanks in part to Mark Romanek's video for "Criminal," which riffed on the Calvin Klein commercial aesthetic of its day, people felt entirely comfortable referring to Apple as a jailbait waif. Thanks in part to her infamous VMA acceptance speech, people felt comfortable making fun of Apple as an entitled, self-serious clown. And thanks to her participation in the inaugural Lilith Fair in 1997, it was a little too easy to lump Apple in with artists like Paula Cole and Meredith Brooks. (In the '90s, people treated "female singer-songwriter" like it was a genre.)

And yet Apple was a full-on pop star. She was 19 when she released her first album, 1996's Tidal. That album sold three million copies, and it captured something. Apple sang beautiful songs, but she also channeled sadness and desperation and ferocity in ways that none of her peers, male or female, could even attempt. Asshole teenage boys like me, as well as the overgrown asshole teenage boys who held media jobs like the one I now have, snarked about things like the "Criminal" video, the VMA acceptance speech, the Lilith Fair. And yet Apple was still a big enough deal to be in heavy MTV rotation, to win a VMA, to play an vital slot at a huge touring festival. She was an important person.

Paul Thomas Anderson was important, too. Anderson second film, 1997's Boogie Nights, was his breakthrough, and it marked the obvious arrival of a major talent. Anderson did not get the sorts of eye-roll reactions as Apple did. He was a man. He was seven years older than Apple. He was a film director, not a pop musician, though he was working in an era when young film directors sometimes found rock-star adulation.

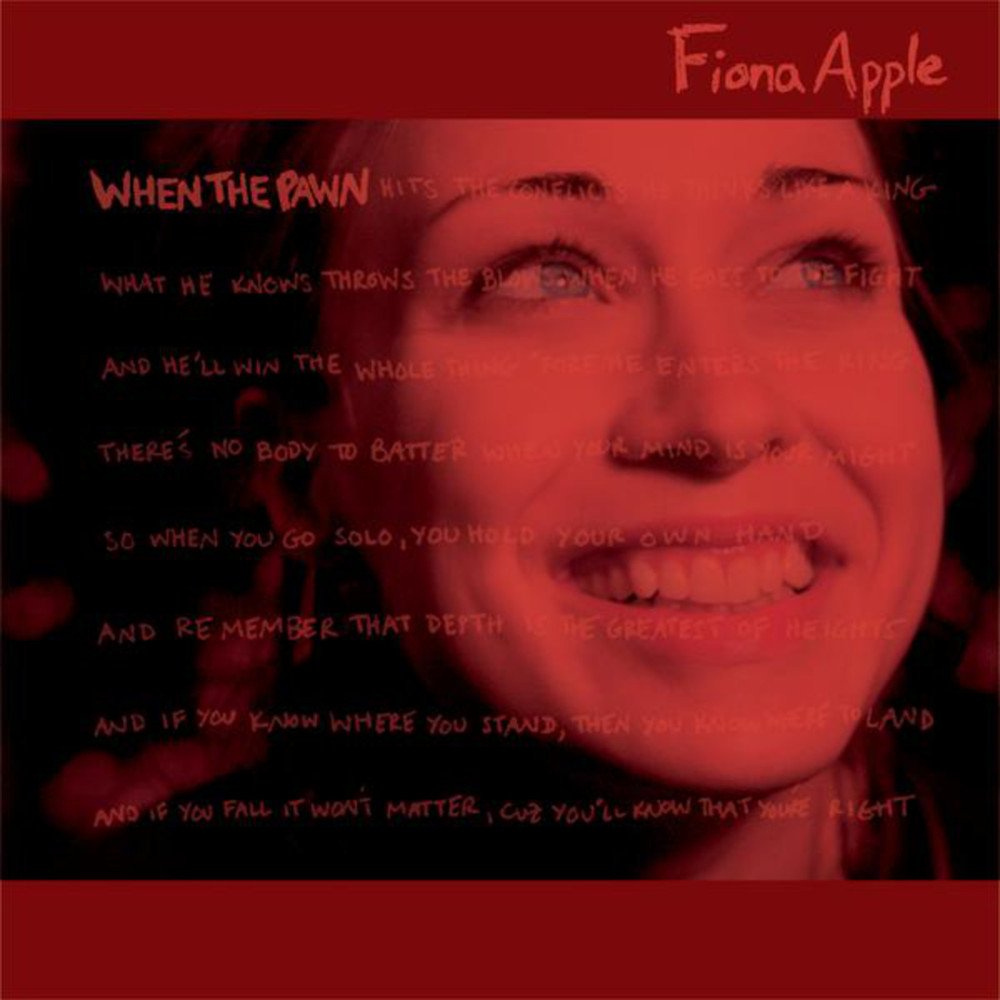

Apple and Anderson became a couple in late 1997 or early 1998, shortly after both of them had become famous. And around the same time, at the end of 1999, they both released masterpieces. When The Pawn..., Apple's second album, came out in early November of that year. (Tomorrow, it will turn 20.) A month later, Magnolia, Anderson's third film, opened in theaters. Both of them were, in their own ways, indulgent works. Magnolia runs over three hours, has no one central character, includes a prominent Tom Cruise dick-print outline, and climaxes with a biblical storm of frogs. When The Pawn...'s full title is a 90-word poem that Apple wrote in response to a dismissive and simplistic SPIN cover-story profile. But in 1999, Paul Thomas Anderson and Fiona Apple could get away with these things, just as they could get away with showing up to a movie premiere in some Fatboy Slim-ass pajamas.

Even with the frogstorm and the impressionistic Aimee Mann singalong and the endless running time, Magnolia, at least as far as I can remember, was not the target of a whole lot of snark. (It's a great movie, but it might've deserved some.) When The Pawn... did, however, get all the snark. Every review of the album had to get in at least three title jokes before it could get into the meat of the album. And yet When The Pawn... was impossible to dismiss. It's a raging, searing, perfect piece of work. It fit into no preestablished genre or trend or pop-music wave. It had no obvious radio singles, no heavy-rotation MTV videos. Instead, it seethed and spat and gnashed. It took all that hate that had been directed at Fiona Apple, absorbed it, and transformed it into something beautiful. We haven't heard anything like it since.

On When The Pawn..., Apple is keenly aware of what the world has done with her image. She pokes that image, twists it, turns it against those who would use it against her. Apple was only 22 when she released When The Pawn..., and yet it's a strikingly adept, mature seen-it-all type of record. Apple gets into the power dynamics of relationships between men and women, understanding the way those things can work at a level that most of us are still working out. She gets cold with it: "It won't be long till you'll be lying limp in your own hands." And she also asserts her own right to fuck things up, to make mistakes. On the song that became the lead single, she even tells the man in her life to leave, for his own sake, right away.

The writing on When The Pawn... remains exquisite a couple of decades later. Fiona Apple has bars. "It's hard enough even trying to be civil to myself." "Please forgive me for my distance / The shame is manifest in my resistance to your love." "You fondle my trigger, then you blame my gun." "I've acquired quite a taste for a well-made mistake." Paul Thomas Anderson has said that, when he was writing Magnolia, he used to go through Apple's notebooks, looking for lines to steal. You can tell.

But it's not just the writing. When The Pawn... pushes against expectations on every level. Apple sings every song on a raw, ragged voice, leaving behind the smooth command she showed on a song like Tidal's "Shadowboxer." And she blows the sound of Tidal into beautiful, jagged pieces. Apple worked on the album with producer Jon Brion, who also scored Magnolia. Brion brings a lot to the album, adding baroque woodwinds and crystalline vintage synths and oblique, tricky arrangements. Brion's work on When The Pawn... is the reason that Kanye West brought him in to co-produce his own 2005 sophomore LP Late Registration, one of the canniest musical decisions West has ever made.

But Brion himself has been clear that he gets too much credit for the album. The thing that really set it apart musically -- the warped, unpredictable rhythms -- are all Apple. The drums on When The Pawn... skitter all over the place. People at the time compared "Fast As You Can" to drum-n-bass, but its darting, twisting ripples owe more to '70s jazz. Meanwhile, "Limp" ends in a legit breakbeat -- a symphony of tumbling drums and squelchy loops and tingling xylophones. Those restless, jittery beats prevent even the prettiest When The Pawn... songs from getting anywhere near prom-ballad territory. They keep the album on its toes.

When The Pawn... is a consciously difficult album in a lot of ways, an anti-pop movie. The album didn't sell the way Tidal had, though it did eventually push its way to platinum without the tiniest shred of radio play. And if you actually listened to When The Pawn..., if you got past the angry little games that the media played with Apple, you heard something glorious. When The Pawn... has not aged at all. The arrangements, the rhythms, the way Apple uses her voice -- they're all as daring and audacious as they ever were. And Apple's scalpel-sharp depictions of the ways that men and women interact with each other are as uncomfortably real as ever. It's a masterpiece, and I can't name a single 1999 album that I like better.

When The Pawn..., great as it was, didn't really change Apple's public image. A few months after she released the album, Apple, distraught over sound issues, ended a show at the New York venue Roseland after only 40 minutes, catalyzing a whole new wave of shitty and judgmental articles. (Roseland always did have terrible sound; she should've never been booked there.) For a long time, Apple thought When The Pawn... would be her last album. It would be a long time before we heard from her again. Her third album would arrive six years after When The Pawn.... Her fourth would come seven years after that. We're still waiting on a fifth.

But when that third album, 2005's Extraordinary Machine arrived, something amazing finally happened. People stopped being shitty about Fiona Apple. I don't remember any articles from that time period attacking Apple for any of her perceived faults or indulgences. People were just happy to have her back. The album got rapturous reviews. When she played another venue a few blocks away from Roseland, she got a hero's welcome. Apple's fourth album was another one with a long and poetic title, and we all lost our shit over it. Years after Tidal and When The Pawn..., and after Apple has become the kind of beloved and semi-reclusive artist who only resurfaces when she's good and ready, it's increasingly apparent that she was an absolutely transcendent pop figure. We're lucky that there was ever a moment when she was showing up to movie premieres.