Duster aren't the only band rising from the dead this week. Melbourne garage-punks Eddy Current Suppression Ring are releasing their first album in nearly a decade, the cheekily-titled All In Good Time, also a worthwhile listen. They're both recent examples of bands coming back after an extended absence to fanfare by those that have continued to listen to them in the years they were away. These comebacks offer an opportunity to solidify a legacy, or start one, among a new generation of listeners, and Duster make for an especially interesting case study in the art of making a grand return.

Their two albums -- 1998's Stratosphere and 2000's Contemporary Movement -- were largely forgotten about soon after they were released, lost to the scarcity of the physical realm because of record label woes and the band's breakup shortly after putting out their second album. The San Jose trio weren't the kind of band that flamed out and left a giant footprint behind, like My Bloody Valentine or Slowdive. Its three members -- Clay Parton, Canaan Dove Amber, and Jason Albertini -- just moved on after breaking up. They quietly made music on their own, and occasionally with each other, but for the most part they simply disappeared.

In the nearly two decades that they were gone, however, they became underground heroes to a certain subset of rockers, popping up as a reference point consistently enough that they were heralded as your favorite indie band's favorite indie band. It's a curious legacy to return to, one that was no doubt helped out by the way that the internet has allowed even long out-of-print records to thrive if championed by the right people. Spreading the gospel of Duster was as easy as sending a link. Earlier this year, their first two albums (and all their rarities) were reissued in a comprehensive box set, the first time these albums have been properly available since they came out, and Duster underwent a critical reevaluation that most overlooked bands from the '90s could only dream of.

Duster are more than deserving of this extended shelf life, and it makes sense that the bands that stumbled across them would want to emulate them. They are musician's musicians, concerned with guitar tones and recording techniques and how best to wrangle intangible emotions out of whatever instruments they happen to be holding. For their reunion shows, they opened for artists like (Sandy) Alex G and Snail Mail, musicians at the head of a larger strain of modern music that push texture to the forefront, from Girlpool to Hovvdy to Horse Jumper Of Love. Unlike a lot today's indie rock, narrative takes a backseat to pure feeling and subtle audio trickery. There's a fastidiousness to Duster's music, one that gets gear nerds frothing but is just as easy for your average listener to grasp.

"The turns and licks of Duster immediately had me under a spell," Girlpool's Harmony Tividad wrote for The Talkhouse last year. "It felt like water, something naturally flowing that already lived in a part of my conscious that I hadn't had access to." The band themselves also have a hard time describing the alchemy that happens when they come together. "We've always been connected in a weird voodoo way," Clay Parton told Vice last year. "Even [when] we've gone months without talking to each other, we can always pick right up." The connection in Duster is instinctual, the kind of effortlessness that only comes when you give yourself over to the pleasure and pain of creation.

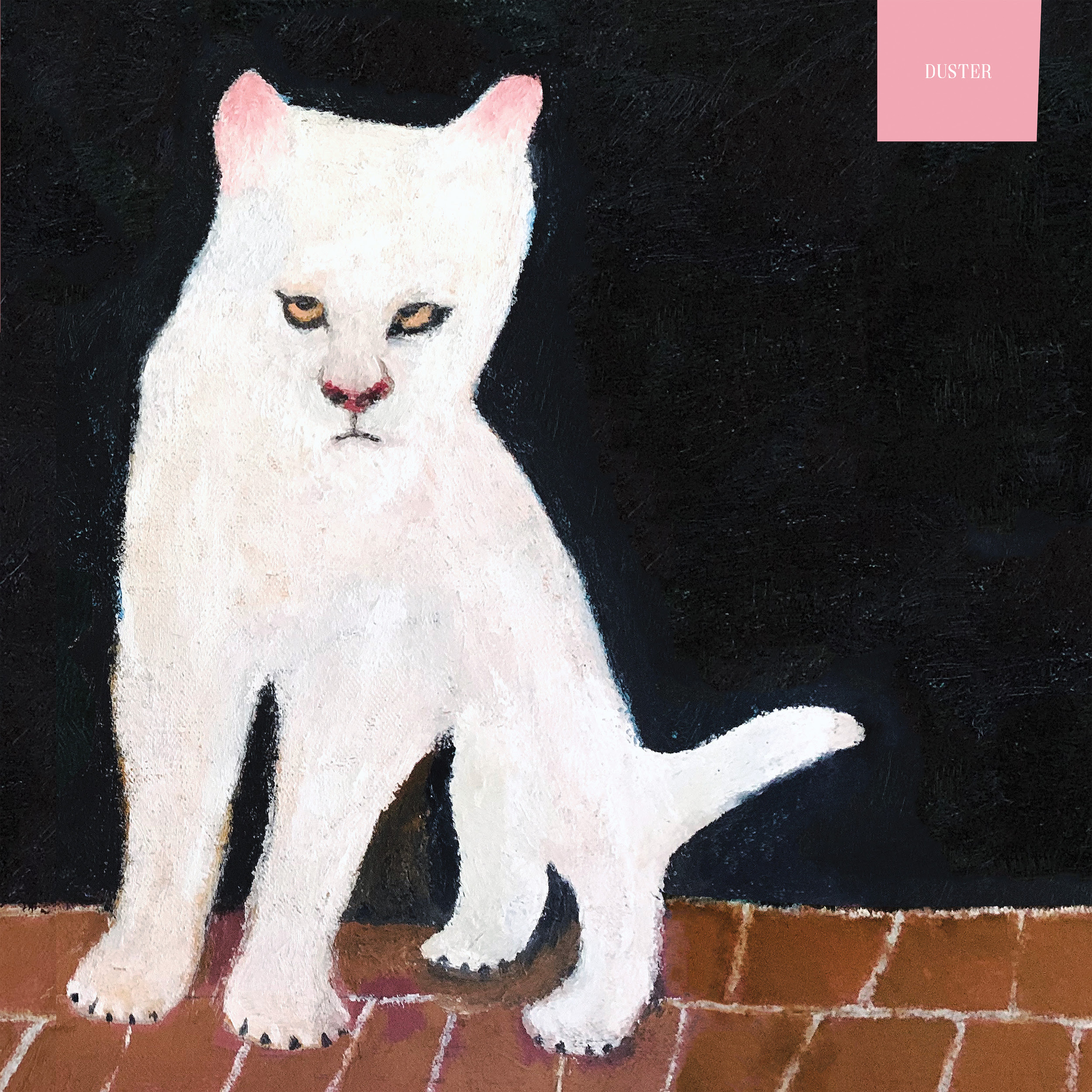

Despite going 20 years between albums, Duster haven't changed too much. Like their first two, they recorded all of their third album, Duster, at home -- in Parton's garage this time. They still record straight to tape; the production quality has improved a bit, largely because technology has made it easier for music to sound better for cheaper, but there are no drastic modifications to their already established sound. "Not much has changed except we have to buy cassettes on eBay instead of steal them from the drugstore now," Parton joked in an interview. Duster basically picks back up where the trio left off -- maybe they're a little less obscure, a little more assured, but mostly they sound like the same band that so many have found inspiration in.

Their songs still luxuriate in the open space provided to them; recording at home certainly alleviates some of the pressure to get stuff done quickly. Duster is heavy and sludgy, and any sense of urgency is sporadic. It's a deep wallow and, like their previous music, the songs on Duster are inspired by celestial wanderings, the feeling of looking up at the stars and realizing how insignificant you really are. That kind of vastness can be both a trap and a release -- it's easy to zone out to Duster, to let it all wash over you in waves, but it's also just as easy to get lost inside the pathways of your own mind, become anxious at the thought of all this space that you're unable to completely get a handle on. It has a lot in common with post-rock in that way, how Duster allow you to project whatever you need to onto their cosmic rumblings.

Their patchwork of ideas is as varied as ever. Stratosphere and Contemporary Movement are both so appealing because they hint at the many different avenues that Duster could travel down within the same lethargic, hissing framework. There are more moments of extreme possibility here: "Damaged" launches itself into a sunny militaristic burst; "Hoya Paranoia" is soft and simple, echoes on echoes spreading out in an amniotic haze. "Ghost World" is the band's version of a grungy ripper, chugging and delightfully off-kilter. The album's early singles, "Copernicus Crater" and "Letting Go," are both stunning in their own right, standout examples of how magnificent it sounds when this band gets locked into a specific groove.

Duster's lyrics are often unintelligible, like radio broadcasts transmitting from a far-off planet. The few phrases that stick out emphasize the same feelings of disorientation and loss that come across through the instruments. Parton and Amber's voices mingle under the surface, coming up for air in gauzy gasps. "The summer war is upon us now," they sing on the languidly apocalyptic "Summer War." "We'll have to take our things and go/ End is coming to take us home, alright." They consistently return to the idea of searching for something that might not be there at all, some grander meaning that feels unreachable.

For anyone that's adopted Duster as a pet cause over the nearly two decades since they put out their last album, Duster must feel like a miracle. I admittedly came to them late, only a few years ago when, like a lot of other people, I noticed their name coming up more and more among artists I like, but it's easy to appreciate Duster's music no matter when you come to it. There's just something so easy about it, like letting yourself slip into the unknown. For a band that had remained a bit of an enigma for so long to return with an album that is so fulfilling is an impressive feat. Duster's legacy will certainly continue on far into the future, beyond even the small circle that they've already assembled for themselves.

Duster is out 12/13 via Muddguts. Pre-order it here.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=tqpWxsT4x1M[/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=Fy8ZE-sJVa0[/videoembed]

Other albums of note out this week:

• Eddy Current Suppression Ring's first album in a decade, All In Good Time.

• Kaytranada's dancey and smooth BUBBA.

• The Free Nationals' groovy guest-heavy debut.

• Stormzy's Heavy Is The Head.

• Harry Styles' boomer pop effort Fine Line.

• Annie Hart's A Softer Offering.

• Russian electronic label трип's locus error compilation.

• The St. Vincent remix album Nina Kraviz Presents MASSEDUCTION Rewired.

• Daniel Lopatin's Uncut Gems soundtrack.

• Mark Ronson Presents the Music of "Spies in Disguise".