Henry Threadgill, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his 2015 album In For A Penny, In For A Pound, has reunited his band Zooid after several years working with larger ensembles on discs like Old Locks And Irregular Verbs and Dirt…And More Dirt. They'll be releasing a new record sometime in 2020, and they recently completed a three-night stand at New York’s Jazz Gallery, where they premiered the new music before heading into the studio. I was there on Friday the 13th, for the third of six performances (two sets a night Thursday-Friday-Saturday).

Zooid consists of Threadgill on alto sax, flute and alto flute; Jose Davila on trombone and tuba; Liberty Ellman on guitar; Christopher Hoffman on cello; and Elliot Humberto Kavee on drums and other percussion. (Kavee was also playing a rack of cymbals and metal plates hanging from strings, a version of the hubkaphone, an instrument Threadgill invented that consists of an assortment of hubcaps hung on a metal frame.) They played six pieces over the course of an hour. Ellman, Hoffman, and Kavee's contributions remained constant, but Threadgill and Davila switched instruments frequently.

A lot of Threadgill's music is built around melodies that are almost pointillistic. Each note is a dot, they combine into relatively simple up-and-down figures, and they arrive in quick succession. The lines being played by the lead instrument, whether it be guitar or flute, often seem to have little to do with what the low-end instruments (tuba, cello) are doing; they're off in their own world. They're all playing simultaneously and at the same tempo, so there's never a feeling that one person is trying to drag the others off track, but they're not really working together, at least not to my ear. So the best approach is to listen to the person who's doing the thing that seems most interesting to you, and then check in on the others when they do something that refracts that in a compelling way.

The first piece featured Threadgill on flute and Davila on tuba. On the second, Threadgill switched to alto flute (a large J-shaped instrument that looks like the pipe under a sink, radically extended) and Davila picked up the trombone, which he played through a mute that made it sound like an old 78.

The third piece was the most interesting. It started with the same combination of instruments as the one before, but Kavee introduced the piece creating an eerie drone by bowing one of his cymbals. That was followed by an unaccompanied guitar solo from Ellman. Later, Threadgill switched back to flute and duetted with Hoffman for quite some time, after which Kavee struck his hanging rack of gongs, then took a drum solo.

For the second half of the set, Threadgill picked up his alto sax, and stuck with it for all three tunes, with Davila shadowing him on tuba. His tone on the alto is fierce and hoarse, emitting sharp cries even when his melodies have a gentle lilt; he sometimes sounds like Ornette Coleman in a fit of rage. He goes hard when playing the flute, too, which may seem unlikely, but it’s true. He hit some notes at the climax of his solos that seemed designed to wake up sleepy audience members, if not rattle photographs off the walls.

In For A Penny, In For A Pound was a two-disc suite with each of the major compositions a kind of concerto showcasing individual group members. These new pieces, at least based on their live versions, are more conventional in structure -- an opening melody, extensive interaction and maybe a solo, and a conclusion, however abrupt. Interestingly, Threadgill himself took his longest solos on the tracks featuring flute; when playing alto, he often limited himself to a short phrase at the beginning and end of the piece, then let the band find their way through the rest of the music. I'm very much looking forward to hearing the studio versions of these compositions.

One of the most intense groups of the early 1960s was the quintet co-led by tenor saxophonists Johnny Griffin and Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis. Most of their recordings, live and in the studio, featured pianist Junior Mance, bassist Larry Gales, and drummer Ben Riley. The latter two men would go on to join Thelonious Monk's band, after having recorded an entire album of Monk compositions with Davis and Griffin.

The band's studio recordings from 1960 and 1961 -- Tough Tenors, Griff And Lock, Lookin' At Monk!, and Blues Up And Down (on which Lloyd Mayers played piano) -- are as intense as hard bop of the era gets. The two saxophonists harmonize superbly, but their solos are where the real hard-blowing action is. And now, the Reel To Real label has issued a previously undiscovered live recording of Griffin and Davis in 1962, with Horace Parlan on piano, Buddy Catlett on bass, and Art Taylor on drums. The title -- Ow! Live At The Penthouse -- says it all. This is a blazing set, first released on vinyl for Record Store Day and now available on CD and digitally. (It’s not streaming, though; you'll have to purchase a copy.) Here’s an exclusive track, a monster version of "Blues Up And Down":

And now, the best new jazz records of the month!

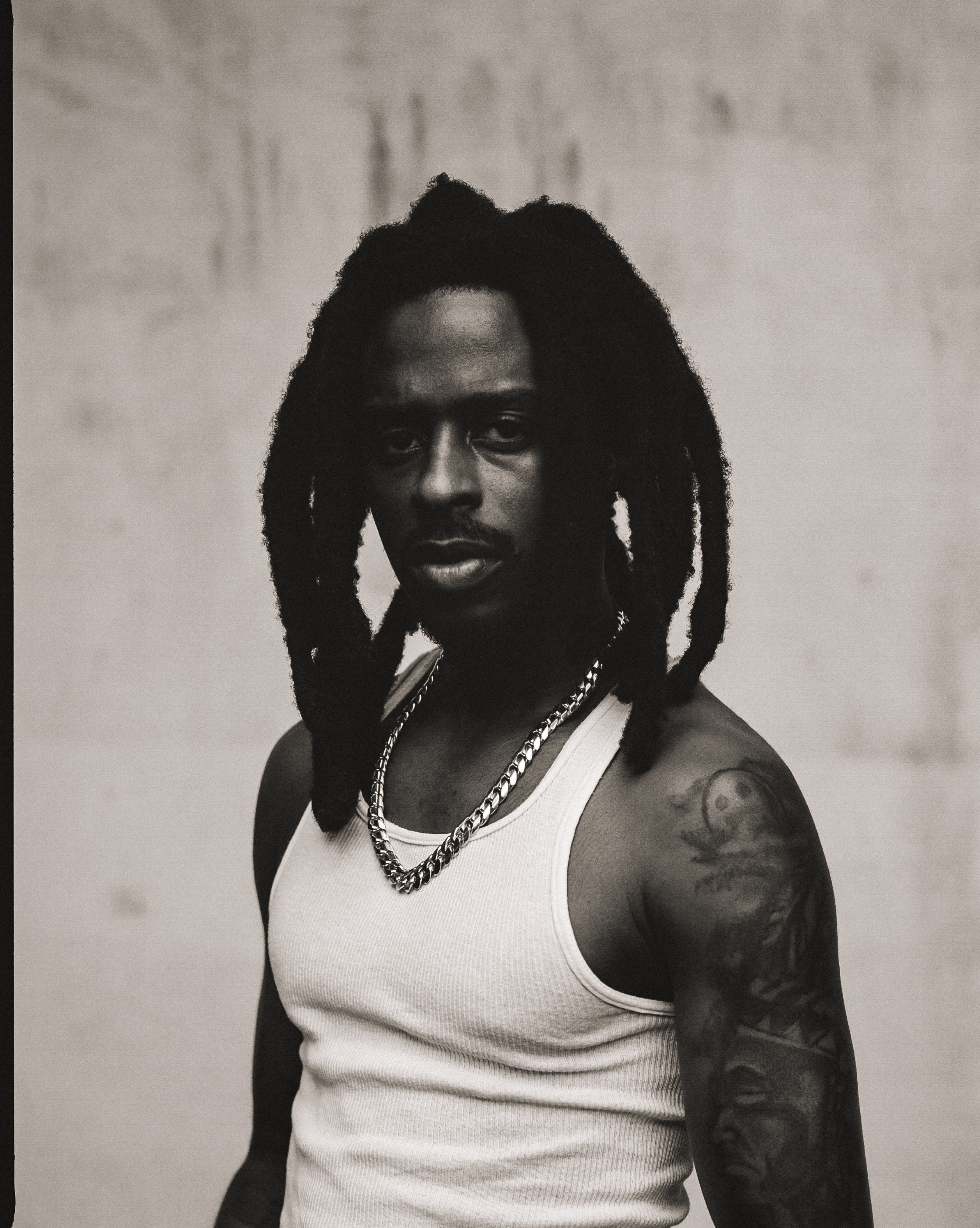

Soweto Kinch, The Black Peril (Soweto Kinch Recordings)

British saxophonist Soweto Kinch's (pictured) latest album is a sharp, politically engaged and musically explosive disc inspired by the race riots and general civil unrest that coursed across the Western world in 1919, including conflicts in Liverpool, Glasgow, Cardiff, Jamaica, and the US (some of which was also portrayed in the HBO series Watchmen). Using a large ensemble of players that combines a jazz group with strings, and moving compositionally from old-timey jazz to modern abstract music, from African and New Orleans rhythms to modern beats, and adding theatrical vocals and historical recordings, this is a kaleidoscopic and vivid portrayal of tension and release and the inevitable crackdown. "Riot Music" sets the stage for much of what follows, with Kinch declaiming radical poetry atop what may initially seem like a goofy, dance-band groove.

Stream "Riot Music":

Bria Skonberg, Nothing Never Happens (Independent/Self-Released)

Bria Skonberg is a Canadian singer and trumpeter whose playing is fierce and hot-blooded, putting a Louis Armstrong-esque blues feel into a variety of contexts, from old-timey jazz to modern soul and funk. Her singing has a traditional jazz tinge, though she sometimes goes beyond breathy into the vocal equivalent of what writer Jia Tolentino calls "Instagram Face": kittenish, sleepy-eyed, and "sexy" in an infantilized sort of way. Her band on this album includes pianist Mathis Picard, bassist Devin Starks, and drummer Darrian Douglas, plus guest appearances from saxophonist Patrick Bartley, organist Jon Cowherd, and guitarist Doug Wamble. Some of the songs are originals, but her recasting of pop and rock tunes are among the highlights. "Blackbird Fantasy" blends the Beatles' "Blackbird," a favorite among jazz musicians, with Duke Ellington's "Black And Tan Fantasy," the combination of guitar, piano, organ, and wailing horns giving it an after-midnight feel.

Stream "Blackbird Fantasy":

Harish Raghavan, Calls For Action (Whirlwind Recordings)

Bassist Harish Raghavan has risen fast in the New York musical community. I've seen him live several times and heard him on excellent albums by Ambrose Akinmusire, Walter Smith III, Logan Richardson, and Dayna Stephens. Now he's emerging as a leader, with a band featuring alto saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins, vibraphonist Joel Ross, pianist Micah Thomas, and drummer Kweku Sumbry. Raghavan produced Ross' debut album Kingmaker, on which Wilkins also played; that led to the formation of this band. The music has a bouncing vitality that makes the occasionally winding melodies and complex rhythms feel natural. "Sangeet," which Raghavan wrote after getting married, carries a joyful charge that comes through in Wilkins' loose-boned solo and the way the band surges behind him.

Stream "Sangeet":

Emmeluth's Amoeba, Chimaera (Øra Fonogram)

Signe Emmeluth is a Danish alto saxophonist living in Oslo, Norway. Emmeluth's Amoeba is her band, with pianist Christian Balvig, guitarist Karl Bjorå, and drummer Ole Mofjell, and Chimaera is their second album, following last year's Polyp. They're all young players, and this is powerful, pounding music as fierce as any free jazz from the '90s. At the same time, though, they can slow down and create moments of near-silent tenderness and sonic exploration. On "Lyons," Emmeluth's blowing is shrill and squealing, as unrestrained and forceful as Charles Gayle. Balvig pounds the piano like a cross between Cecil Taylor and Don Pullen, letting loose thunderous rumbles and high-speed runs. Bjorå's guitar has the sting of Sonny Sharrock, and Mofjell's drumming is neck-breaking, his solo like an attempt to hit everything within reach at least twice, as fast as possible.

Stream "Lyons":

Antoine Berjeaut, Moving Cities (Musiques Au Comptoir/I See Colors)

French trumpeter Antoine Berjeaut and globetrotting, Chicago-based drummer Makaya McCraven assembled this album from sessions in France, Belgium, and the US, put together to coincide with concerts. The band features saxophonist Julien Lourau, bassist Junius Paul, guitarists Guillaume Magne and Matt Gold, Arnaud Roulin on synths, and Lorenzo Bianchi Hoesch on live electronics and FX. The combination of Berjeaut's fierce horn, the surging waves of electronics, the stinging guitar, and McCraven's manic breakbeats brings to mind trumpeter Tim Hagan's two electronic, drum 'n' bass-driven albums from the turn of the century, Animation/Imagination and Re-Animation Live!, made in collaboration with the late, open-eared producer and saxophonist Bob Belden. "Shadows" is a wild live eruption, nearly nine minutes of headlong frenzy; periodically, whoops of exultation can be heard from the crowd.

Stream "Shadows":

Fred Anderson Quartet, Live Vol. 5 (FPE)

This raw live recording, from December 1994, features legendary Chicago saxophonist Fred Anderson joined by one of his regular rhythm sections, bassist Tatsu Aoki and drummer Hamid Drake, and one very special guest: Japanese trumpeter Toshinori Kondo. Kondo, who favors a rack of electronic effects, has recorded with DJ Krush, and is a longtime member of Peter Brötzmann's Die Like A Dog quartet. His twirling, streaming ribbons of sound are about as far away from Anderson’s earthy, bluesy, riff-based improvisations as it's possible to get, but Drake (also a member of Die Like A Dog, and one of the planet’s greatest drummers) creates a zone where each man can listen to and appreciate the other's ideas. "Probability Distribution" opens with two minutes of Anderson alone before Kondo comes in like fog drifting under the door. By the end, the trumpeter is creating waves of sputtering electronic noise as Aoki frantically bows his bass and Drake lays down pattering hand-drum rhythms.

Stream "Probability Distribution":

The Dopolarians, Garden Party (Mahakala Music)

This album is a tribute to New Orleans drummer Alvin Fielder; it was his final recording session, in June 2018. He died in January of this year. The band includes tenor saxophonist Kidd Jordan, alto saxophonist Chad Fowler, pianist Christopher Parker, bassist William Parker, and vocalist Kelley Hurt. The music is free jazz, but it's not the blaring, assaultive kind; instead, it's shot through with joy and life energy. Fielder is an outrageously swinging drummer, and he propels the 12-minute "Guilty Happy" through multiple sections -- a manic, relentless first half, featuring many, many variations on the core melody, occasionally adorned with wordless vocals; a more ballad-like middle section; and a romping finale -- without ever letting the music flag or fade.

Stream "Guilty Happy":

Erik Truffaz, Lune Rouge (Warner Music France)

Erik Truffaz should be too old to be making music this cool. He's almost 60, but he writes and plays like a man half that age. On this album, his first in three years and his first with new drummer Arthur Hnatek, he plays simple, breathy melodies halfway between Miles Davis and Arve Henriksen over electronics-tinged tracks from keyboardist Benoit Corboz and bassist Marcello Giuliani. Some songs, like "Reflections," which features vocalist José James, have a softly swaying R&B feel. But the nearly 12-minute title track is a deep, thumping house-fusion jam; its rock-steady kick drum and gently layered keyboards could have been released on the Kompakt label, and Truffaz's horn ripples out in waves of echo and reverb.

Stream "Lune Rouge":

3TM, Lake (We Jazz)

3TM is a trio led by drummer/producer Teppo Mäkynen and featuring tenor saxophonist Jussi Kannaste and bassist Antti Lötjönen. This is their second release, but Mäkynen created a solo ambient electronic album, Abyss, to serve as a bridge between the two. The influence of electronic mood music is strong on this record. In addition to drums, Mäkynen plays vibes here and there, and uses reverb and other effects to make the music extremely atmospheric. "A Pile Of Broken Dreams" has a strong melody and swings powerfully, but the addition of the vibes and the hissing, foggy production gives it a dreamlike quality that makes it seem like you've just stumbled into the performance space from a frigid Finnish winter night, and your ears aren't fully capable of processing the sounds yet.

Stream "A Pile Of Broken Dreams":

Maciej Obara Quartet, Three Crowns (ECM)

Polish alto saxophonist Maciej Obara's second album with his quartet featuring pianist Dominik Wania, bassist Ole Morten Vågan, and drummer Gard Nilssen includes six original compositions and two free interpretations of melodies by composer Henryk Goreçki. This combination of elements -- two Polish musicians, two Norwegian musicians, signed to ECM, interpreting Goreçki -- adds up to about what you'd expect. This is a very beautiful, rain-on-the-window sort of album that sets and maintains a mood of calm and stillness, with few exceptions. The title track, named for a mountain range in Poland, is one of the most high-energy pieces on the record; Nilssen dominates in a way he doesn't elsewhere, fueling excited performances from both Wania and Obara, as Vågan keeps a strong heartbeat going at the center of it all.

Stream "Three Crowns":

Fish & Steel, Fish & Steel (PNL)

Drummer Paal Nilssen-Love has pulled two members -- trombonist Mats Äleklint and tuba player Per-Åke Holmlander -- out of his Large Unit to form this trio. Their debut album was recorded at two September 2018 concerts in Oslo and Stockholm, and while these two roughly half-hour tracks get raucous and wild at times, as one might expect with that instrumentation, there are also a lot of quiet passages where both brass players are huffing and puffing at the very bottom of their instruments' range, the trombone growling like a dog with its head stuck in a bucket as the tuba whimpers and moans like a truck engine that really doesn't want to start. Nilssen-Love doesn't drive the music so much as egg the other two on.

Stream "Blow Out":

Eric Alexander, Eric Alexander With Strings (HighNote)

Tenor saxophonist Alexander is joined by pianist David Hazeltine, bassist John Webber, drummer Joe Farnsworth, and the titular strings (arranged and conducted by Dave Rivello) on this short -- six tracks, 36 minutes -- but lush album. He performs tunes made familiar by Sarah Vaughan, Horace Silver, and Chet Baker, among others, each one a tender ballad delivered at a swaying tempo. "Dreamsville," written by Henry Mancini, floats by like a cloud with Alexander delivering impassioned but tasteful variations on the melody through a thick, buzzy tone reminiscent of Lester Young or Coleman Hawkins; Hazeltine gets a very brief turn in the spotlight, but makes the most of it.

Stream "Dreamsville":

Amund Kleppan, Venture (AMP Music)

Norwegian drummer Amund Kleppan is a relatively new name, but he's already played with Polish pianist Marcin Wasilewski, among others. This group features Julius Gawlik on saxophone and clarinet; Dima Bondarev on trumpet; Tal Arditi on guitar; Rasmus Sørensen on piano; and Julian Haugland on bass. The music is high-degree-of-difficulty hard bop in the vein of the mid '60s Miles Davis quintet; Gawlik sounds particularly Wayne Shorter-esque on "Reach," and Sørensen and Kleppan drive the band hard, as Haugland bounces along between them. Bondarev delivers a tender but high-energy solo and bonds loosely with the saxophonist on the melody, while Arditi mostly stays out of the way.

Stream "Reach":

Various Artists, Hometown: Detroit Sessions 1990-2014 (!K7 Music)

Tribe -- a musical collective, a label, a source of energy and inspiration for Detroit-area avant-garde jazz musicians -- was a strong force in the early 1970s. Saxophonist Wendell Harrison and trombonist Phil Ranelin led their own groups and released albums by others. As time went on, things got tougher, for artists and everyone else, but Tribe persisted. This compilation gathers tracks from albums by Ranelin, Harrison, and pianists Pamela Wise and Harold McKinney, which run the gamut from poetry to hard-grooving soul jazz. McKinney’s "Juba" features a chanted poem you could jump rope to, fueled by high-speed handclaps, which eventually develops into a fierce hard bop tune with tough trumpet, saxophone, piano and trombone solos.

Stream "Juba":

Various Artists, If You're Not Part Of The Solution: Soul, Politics And Spirituality In Jazz 1967-1975 (Ace)

The Ace label from the UK puts out amazing compilations. They've currently got a series going, assembled by music critic Jon Savage, that charts the changes in pop and rock from the mid '60s to the early '70s, and they’ve put together a whole string of titles over the past few years that showcase spiritual, free, and funky jazz from the same era. This is one of the best. It features tracks from Clifford Jordan, Gary Bartz's radical early '70s group NTU Troop, Azar Lawrence, and lesser-known acts like Catalyst and Funk, Inc. The title track is by Joe Henderson, and it opens the disc with over 11 minutes of fiery live action featuring Woody Shaw on trumpet, George Cables on electric piano, Ron McClure on bass, Lenny White on drums, and Tony Waters on congas. The compilation itself is physical-only and doesn’t exist on streaming services, but here's the title track.

Stream "If You’re Not Part Of The Solution, You're Part Of The Problem":