In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

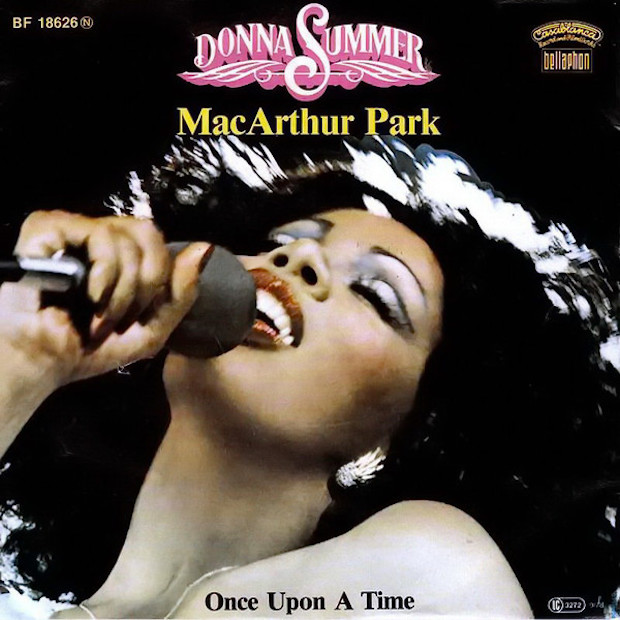

Donna Summer - "MacArthur Park"

HIT #1: November 11, 1978

STAYED AT #1: 3 weeks

What sense can you even make out of "MacArthur Park"? The song's lyrics, which people still joke about decades later, are plenty strange on their own. But the whole saga of "MacArthur Park" -- as a song, a standard, and a cultural phenomenon -- is a whole lot weirder than the infamous image of a cake left out in the rain. "MacArthur Park" is the sort of thing that can't possibly be repeated -- a bugged-out psychedelic easy-listening folk-rock experiment that became a hit, a punchline, and finally a disco chart-topper. And it might be even weirder that Donna Summer, easily the greatest and the most popular artist ever to come out of the disco universe, only finally landed her first #1 hit when she took on this piece of melodramatic '60s kitsch.

There is a lot of backstory here. Jimmy Webb, the man who wrote "MacArthur Park," came from a repressively religious Oklahoma household and studied music at college in San Bernadino. He became a songwriter in Los Angeles in the '60s and had early success working with people like Johnny Rivers and the Fifth Dimension. (Webb wrote the Fifth Dimension's 1967 single "Up, Up And Away," which peaked at #7. It's a 3.) Later on, Webb struck up a great working partnership with Glen Campbell, and the two made some classics together after Campbell recorded his immortal version of "By The Time I Get To Phoenix," a song that Webb had written for Johnny Rivers. In 1968, Campbell's Webb-written "Wichita Lineman" peaked at #3; it's a 9. A year later, Campbell hit again with the Webb-written "Galveston"; that one is an 8.

When working with the Fifth Dimension, Webb, a producer himself, had gotten friendly with their producer Bones Howe. Howe was working with the folk-pop hitmakers the Association.In 1967, Webb had the idea to write an ambitious, classical-influenced pop song full of different movements and motifs. (Depending on who you ask, Howe might've challenged him to attempt it.) So Webb went deep into his zone and came up with a 22-minute cantata. His idea was that the Association could fill up a side of an album with the cantata and that they could break little pieces of it off and release them as singles. The final movement of that cantata was "MacArthur Park," a vaguely hysterical breakup song that Webb had written after splitting from a girlfriend.

Lyrically, "MacArthur Park" seems like a bugged-out flight of fancy, but Webb insists that all the details in it are based on real things that he experienced in one way or another. His ex worked in an insurance office near MacArthur Park in Los Angeles, so he'd go meet her for idyllic lunches there. Sometimes, she'd wear a yellow dress. Old men would play Chinese checkers in the park. Someone really did leave a cake out in the rain at some point, and Webb liked the idea that the image could serve as a metaphor for love crumbling.

Because this was the late '60s, Webb could write all these minute details out as dramatic flourishes without feeling like he had to explain any of them. And because he wrote about them with such strange, feverish emotion, the lyrics come out looking vivid and surreal. In any case, there is an emotional core to the song, and Webb spells it out on the bridge: "There will be another song for me, and I will sing it / There will be another dream for me / Someone will bring it." So "MacArthur Park" is a song about romantic resilience, about knowing that you'll be able to make it through a tough period. But because of the strange tactile specificity of that "cake out in the rain" chorus, that's not how anyone remembers it.

It's a small miracle that anyone got to hear "MacArthur Park" at all, really. The Association did not like the idea of turning over a whole album side to Jimmy Webb's crazy idea, so they passed. Webb, supremely bummed when the Association turned him down, buried "MacArthur Park," figuring he'd never release it in any capacity. At a Los Angeles fundraiser, though, Webb met Richard Harris.

Richard Harris, the future Albus Dumbledore, was an actor, not a singer. Harris had come from Ireland, worked his way up through the London theater scene, and started acting in movies in the late '50s. He'd been in The Guns Of Navarone and Mutiny On The Bounty, and he'd been nominated for an Oscar after playing an angry young rugby player in 1963's This Sporting Life. In 1968, when Harris met Webb, he was surfing a moment of fame. He'd played King Arthur in the big-budget 1967 musical adaptation of Camelot, and he'd been nominated for another Oscar for that one. That role involved singing, and he'd handled himself capably enough. So Harris had the idea that he could make an album, and he wanted to make it with Jimmy Webb.

Webb flew to London to work on music stuff with Harris, and "MacArthur Park" was at the bottom of his pile of songs. Harris liked it, so Harris recorded it in Los Angeles, with members of LA's Wrecking Crew aces backing him up. Webb produced the song, and he played harpsichord on it, too. It's a beautiful, fascinating trainwreck of a track, a lush and ultra-serious psychedelic adult-contempo nightmare. Harris sings it all in a stentorian quaver, which makes the song both grander and sillier. It hits a note of great nonsensical fervor when he gets to the bit about the cake in the rain on the chorus: "I don't think that I can take it! Because it took too long to bake it! And I'll never have that recipe agaaaaiiiiin! Oh, noooooo!"

Harris' "MacArthur Park" is an admittedly ridiculous piece of music, a wild operetta of inarticulate regret. The track regularly pops up on snarked-out worst-song-ever countdowns, andI don't agree with that at all. I respect its absurdity. In any case, "MacArthur Park" turned out to be an important record. At more than seven minutes, it was, at the time, the longest hit single ever made, and it helped make the world safe for similarly indulgent epics like the Beatles "Hey Jude," which came out a few months later.

"MacArthur Park," in its original Richard Harris form, peaked at #2. (It's a 6.) It didn't fade away after that, either. It stuck around. Waylon Jennings won a Grammy for a 1969 country version of the song. The Four Tops turned it into orchestral soul in 1971. Andy Williams cut a sleepy easy-listening version in 1972. In his 1975 audition for the original Saturday Night Live cast, Andy Kaufman gave a straight-faced spoken-word recitation of the "MacArthur Park" lyrics. Someone, somewhere, was going to turn "MacArthur Park" into a disco song. It was inevitable. We're lucky we got the Donna Summer version.

Donna Summer's history is pretty long and involved, too. Born LaDonna Gaines in Boston, she dropped out of high school and moved to New York to sing for a blues-rock band called Crow. When the band broke up, she auditioned for the Broadway musical Hair and was cast in the Munich version of it. So she moved to Germany and spent years onstage in Munich and Vienna. She sang in musicals there, learned German, and briefly married an Austrian actor named Helmuth Sommer. When she cut her first single, a 1968 German-language version of the Hair song "Aquarius," the label mistakenly printed her name as Donna Summer, and she stuck with it.

While living in Munich in 1974, Summer met the producers Giorgio Moroder and Phil Bellote, and they started working together, making records that hit first around Europe and then made it to the US just as the disco boom was taking shape. In Munich, the three of them helped develop a whole new sound -- a dizzily repetitive synth-based take on disco that edged its way toward psychedelia. That sound could be thin and numbing even when it hit. Another Munich group, Silver Convention, had a #1 hit with that sound in 1975's "Fly, Robin, Fly." But Silver Convention turned out to be a short-lived novelty. Summer, on the other hand, became a star in a genre that wasn't really geared toward producing stars.

The difference is that Donna Summer was great. Moroder and Bellote were visionaries with wide-reaching ambitions and solid-gold ears. They had one of those mysterious chemical relationships with Summer, who had a sleek rocket of a voice that could weightlessly explode over their tracks. Summer wasn't a traditionally soulful black American singer; there was never a lot of gospel in her voice, even though she did grow up singing in church. Rather than grit, she had musical-theater polish and feeling. She could convey emotion with sweatless subtlety and big-voiced bravado. And she wasn't above gimmickry.

Summer first hit with 1975's "Love To Love You Baby," a long orgasm odyssey that she co-wrote with Moroder and Bellote. ("Love To Love You Baby" peaked at #3; it's a 10.) After that, she made an absolute pop masterpiece with 1977's "I Feel Love," the song that more or less invented synthetic dance music as we know it today. (That one peaked at #6; it's another 10.) Summer's 1978 smash "Last Dance" -- done for the soundtrack of the comedy flop Thank God It's Friday, which starred Summer alongside Jeff Goldblum and Debra Winger -- switched things up, starting off as a ballad before abruptly locking into a groove and becoming something else. The song has lasted a lot longer than the movie it was written for. ("Last Dance" peaked at #3; it's a 9.)

So Donna Summer was an absolute hit machine by the time she finally hit #1 with "MacArthur Park." But she also had aspirations. Summer's early albums like A Love Trilogy and Four Seasons Of Love were conceptual song-cycles built around heady themes. Moroder and Bellote were pop maximalists with prog-rock aspirations. Like Jimmy Webb a decade before, they filled up records -- even the stark electronic ones -- with orchestral flourishes and big ideas, rendering their melodrama as grandly as they could. Like Richard Harris, Summer had started out acting onstage, so she was fully ready to jam as much emotion as possible into the almost-nonsensical "MacArthur Park" lyrics. She'd also gotten sick of the meditative coos that so many of her previous Moroder/Bellote hits had required. She wanted to really sing. "MacArthur Park" gave her a chance to do that.

"MacArthur Park," like Marvin Gaye's "Got To Give It Up (Part 1)" before it, was a studio track recorded for a live album. Summer had three sides' worth of live material for the double live LP Live And More. For the double album's final side, she worked with Moroder and Bellote to put together an 18-minute suite of music built around "MacArthur Park" -- Jimmy Webb's cantata dream, realized a full decade later. (Another track drawn from that suite, "Heaven Knows," also became a hit on its own. "Heaven Knows" peaked at #4; it's a 9.)

The idea of a live Donna Summer album seems faintly ridiculous, since Summer's best songs sound like such studio creations. But the album works. Summer was a slick, practiced singer who could bring her records to life in front of actual people, and she had a great band working with her. Live And More was a huge hit, too, becoming the first Donna Summer album to hit #1. In fact, Live And More was #1 on the album charts at the same time that "MacArthur Park" topped the Hot 100, improbably making Summer the first artist ever to score simultaneous #1s on the album and singles charts.

As with the Richard Harris original, Summer recorded "MacArthur Park" with the best LA studio musicians that her producers could round up. Moroder found other ways to put his literal voice into "MacArthur Park." On the chorus, the backing vocals are Moroder himself, multi-tracked into a chorus. It's a trick that other producers would use many, many times in the decades ahead, but nobody else was doing stuff like that then. In the four-minute single edit of the song that Moroder put together, we get a swirling, histrionic, string-dominated intro that recalls the original. But then, one minute in, the beat drops, and "MacArthur Park turns into a gloriously hard-thumping disco jam. Summer lets out a quick whoop, but she keeps her composure, and she works overtime to keep the song's strange emotional resonance alive.

"MacArthur Park" is a minor Donna Summer work, so it's slightly disappointing that the song was the first to really break through when so many better Summer songs fell short of #1. But on its own merits, "MacArthur Park" is hard to hate. Moroder and Bellote just pile on the effects: Horn-stabs, screaming rock guitars, noodling keyboard solos. But it's always anchored to that beat and to that miraculous voice.

Jimmy Webb wasn't really making hits anymore by the time of Summer's "MacArthur Park" cover. He'd become a critically beloved but low-selling singer-songwriter, so the reappearance of "MacArthur Park" was a happy surprise for him. (Later on, Webb would write things like the America songs from the great 1982 cartoon movie The Last Unicorn and the theme for the TV show E/R -- the short-lived '80s sitcom, not the long-running hit '90s drama.) Webb is still around and still playing music, but "MacArthur Park" is the only #1 that he's ever written.

"MacArthur Park" would not, however, be the final #1 for Donna Summer, Giorgio Moroder, and Pete Bellote. All of them will return to this column. They had that recipe again.

GRADE: 7/10

BONUS BEATS: The Pet Shop Boys, a group that will eventually appear in this column, sampled Donna Summer's version of "MacArthur Park" on their 1999 single "New York City Boy." Here it is:

THE 10S: The Rolling Stones' endlessly graceful quasi-country purr "Beast Of Burden" peaked at #8 behind "MacArthur Park." It's a pretty pretty pretty pretty pretty pretty song, and it's a 10.