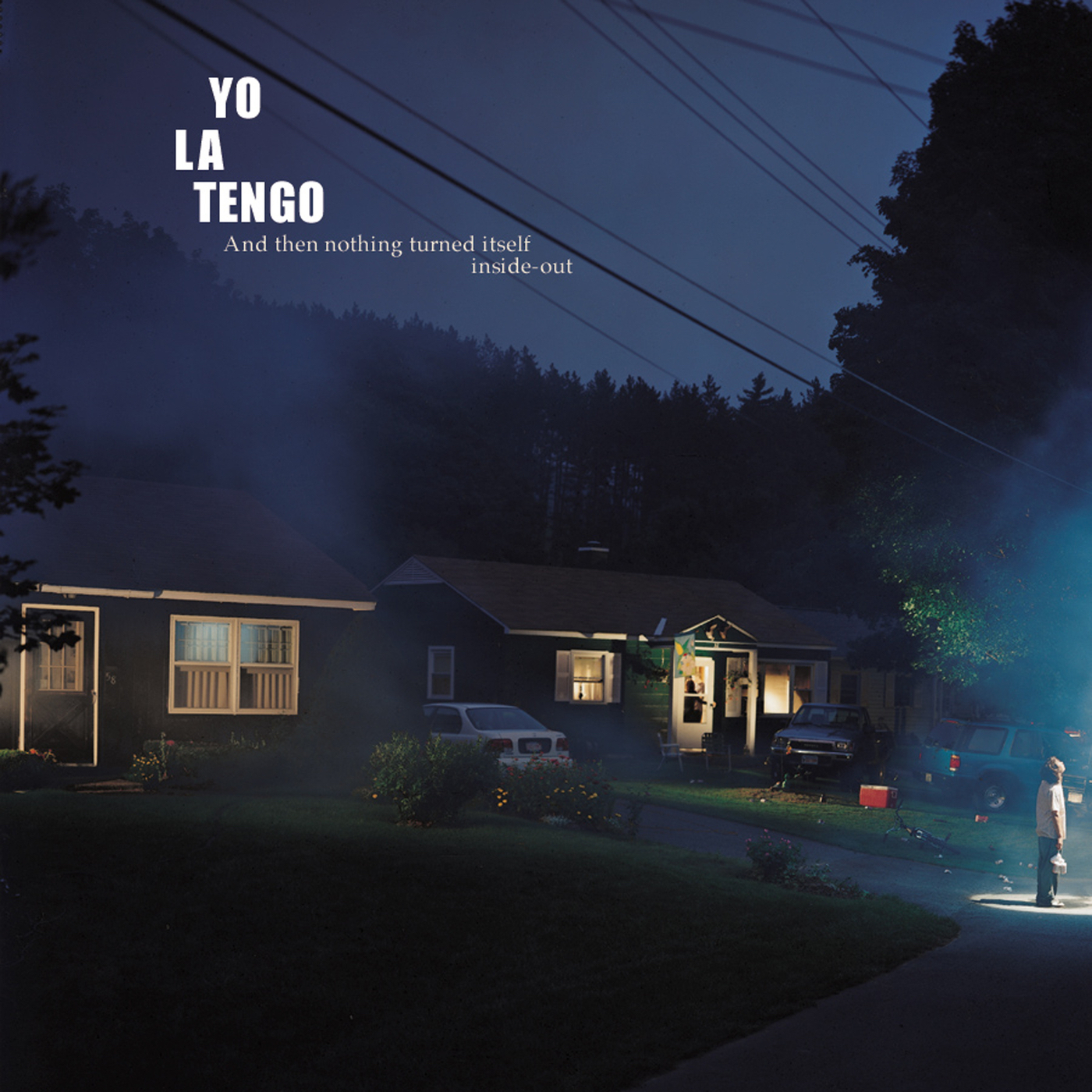

Some albums are meant to be listened to after dark. Yo La Tengo telegraphed such intentions for And Then Nothing Turned Itself Inside-Out with the cover art, a cozy nighttime suburban scene in which something extraterrestrial appears to be happening just outside the frame. It's fitting imagery for an album on which Ira Kaplan and Georgia Hubley breathe supernatural beauty into their sighing domestic bliss. But really no such accompaniment was necessary to establish And Then Nothing's nocturnal bona fides. All you have to do is press play.

To steal a phrase from their most beloved sport, Yo La Tengo had established themselves as superstar utility players by the time And Then Nothing came out 20 years ago this weekend. They'd been a band for 16 years, more than half of that time with the core lineup of Kaplan, Hubley, and James McNew -- typically on guitar, drums, and bass respectively, though anyone who's seen a Yo La Tengo show knows how often they like to swap instruments. There was no consistent lead singer; instead, the members' voices played off each other, each one coming to the forefront as the songs demanded. In keeping with that mix-and-match impulse, Yo La Tengo's albums began showing off a broad assortment of styles, too. That patchwork-quilt approach reached its apotheosis on 1997's I Can Feel The Heart Beating As One, a shortlist contender for the greatest indie rock album of all time.

The album's glory was the way it veered effortlessly between genres, from droning noise-pop to twangy folk-rock to tense electro-organic grooves to languid guitar ballads. Part of the appeal was the gleeful way they seemed to be toying with their record collections. Their Beach Boys cover sounded like the Velvet Underground. They reimagined Anita Bryant's fluttery 1960s pop hit "My Little Corner Of The World" -- already transformed into a country song by Marie Osmond -- as jaunty dead-eyed twee like Belle & Sebastian making elevator music (years before the world found out what Belle & Sebastian elevator music actually sounded like). They recorded a slow-burn epic that sounded like the Earth being swallowed up by distortion and called it "We're An American Band." These three could do a little bit of everything, and everything they were doing was awesome.

For Yo La Tengo to follow up their eclectic masterpiece by locking into a single mood for 78 minutes was shocking. Yet that's essentially what they did with And Then Nothing Turned Itself Inside-Out. With the exception of the Sonic-Youth-gone-shoegaze joyride "Cherry Chapstick," the entire album was deeply, monumentally chill, from its eerie opener "Everyday" to its closing 19-minute feedback lullaby "Night Falls On Hoboken." Some fans didn't know what to make of it, including Pitchfork founder Ryan Schreiber, who half-jokingly decried the album as lifestyle music to be purchased by yuppies at Barnes & Noble. (Fortunately, it still ended up on their year-end list, which basically introduced teenage me to indie rock when I clicked over from a Radiohead fan site and realized I'd never heard of the rest of the artists.)

Rob Brunner at Entertainment Weekly was more immediately smitten with the album's "gentle musical love story," favorably comparing it to "eavesdropping on a whispered late-night conversation between Ira Kaplan and Georgia Hubley, the band's happily married front couple." That is exactly the vibe And Then Nothing conjures. I imagine listening to these songs is the closest I'll ever come to being James McNew: You get to be the third wheel picking up a contact high off Kaplan and Hubley's lovestruck reverie, basking in good company with great taste.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

It's not that the songs on And Then Nothing were without precedent. Yo La Tengo's catalog is strewn with moments of gorgeous quiet amidst the noise, particularly on the '90s Matador albums that cemented their underground fame. And it's not like the trio had abandoned their adventurous spirit; working with longtime producer Roger Moutenot, they continued to explore a wide range of genres and textures with the perspective that made them critical favorites and the ideal punchline for the classic Onion article "37 Record-Store Clerks Feared Dead In Yo La Tengo Concert Disaster." It's just that coming from a band that gave us fuzz-pop anthems like "From A Motel 6," "Tom Courtenay," and "Sugarcube," And Then Nothing's unified calm represented a surprising shift.

The reason for the change may have been practical. Kaplan and Hubley had recently returned to Hoboken, New Jersey, where they founded the band in 1984, after years living in Brooklyn. "The small town aspects of Hoboken are very appealing," Kaplan later told The Guardian. "And our music got a lot quieter because we weren't competing with eight other bands in a Brooklyn rehearsal space." I imagine returning to their hometown fueled nostalgic reflections like "Our Way To Fall" and "Last Days Of Disco" -- two achingly beautiful songs about the thrill of young love -- to say nothing of the psychological effects of settling down in the suburbs.

For an album named after a Sun Ra quote about the origin of the universe, And Then Nothing's world is extremely small. Yet that world teems with the joy of creation, just like any other Yo La Tengo album. The Simpsons-referencing "Let's Save Tony Orlando's House" is carried along by a hypnotic current of organ, while a looped vocal sample and elegant strings completely reinvent George McCrae's proto-disco classic "You Can Have It All." The range of drum sounds is particularly impressive: the tinny programmed beat on "Saturday," the deconstructed tumble behind "From Black To Blue," the gentle brushstrokes shaping the blurred edges of "Last Days Of Disco." The scenes are no less vivid just because they all seem to take place between sunrise and sunset within one household.

It helps that the household in question belongs to Kaplan and Hubley. Their life together has long been aspirational. Here are two unglamorous everyday people who've carved out a humble living literally making beautiful music together, for a devoted audience, at a manageable scale, away from the scrutiny of the celebrity media microscope. They are living the dream, and the dreamy And Then Nothing Turned Itself Inside-Out is the album that crystallized that perception. Its most enduring songs are its most tenderly affectionate, the ones that glimpse those moments of intimacy we spend our lives chasing.

Yet despite its many halcyon visions of romance, And Then Nothing's portrait of domesticity is honest and well-rounded. "Everyday" begins the tracklist with a nod to ennui and the numbing power of routine: "Looking to embrace the nothing of the everyday." Alongside the inside jokes and swoons are realistic details from Kaplan and Hubley's conflicts and struggles. "Tears Are In Your Eyes" deals with the challenge of comforting a partner through depression. "From Black To Blue" explores accountability and the difficulty of articulating what lies deep within. "Don't have to smile at me, don't have to talk," goes the hook from "The Crying Of Lot G," a chronicle of slammed doors and communication breakdowns. "All that I ask is you stop and remember it isn't always this way."

Nor would it always be this way for Yo La Tengo going forward. Upon the release of 2003's less rewarding Summer Sun, it seemed the band might retire into the calm forever, but by 2006's I Am Not Afraid Of You And I Will Beat Your Ass they were back to zigzagging across the sonic spectrum. They would live to rock again. Yet in hindsight And Then Nothing does feel like the end of an era, both a capstone for Yo La Tengo's breathtaking '90s and a portal to their future as wise indie-rock elders. Despite their legendary stature, they seem to exist further outside the spotlight than ever now, which suits them. As they proved two decades ago, they sound incredible in the dark.