Reaching the milestone of 40 trips around the sun may no longer have the same gravity that it once did. Take for instance the first week of the NFL playoffs this January, when three of the eight competing teams were helmed by quarterbacks of that vintage, including Tom Brady of the New England Patriots at a ripe 42. Then again, those three teams all lost in upsets, so maybe the milestone still has some weight to it.

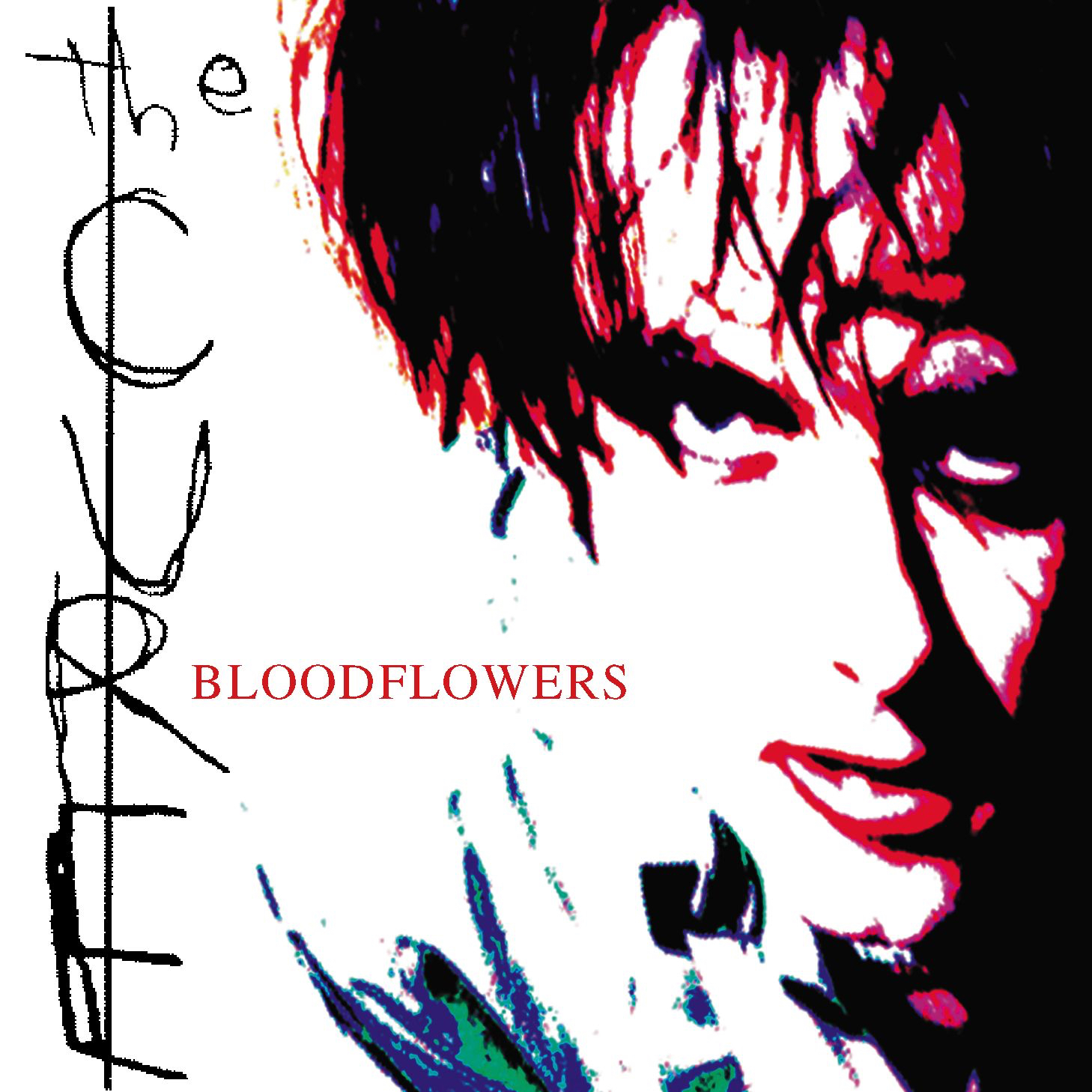

As his 40th birthday approached, the Cure's Robert Smith could feel himself being pulled inexorably over the hill. "So the fire is almost out and there's nothing left to burn," he frets throughout "39," the penultimate track on Bloodflowers, the Cure's 11th studio album. "I've run right out of thoughts and I've run right out of words/ As I used them up, I used them up." Little wonder that upon release it was strongly indicated that the record was to be the band's last.

In the niche category of songs dedicated to a specific numerical age, an unsurprising majority focus on hormone-fueled teenage years or one's early twenties when new freedoms are reveled in. On occasion songwriters will find that those thrills wear off too soon. In "24," one of Red House Painters' earliest crawls, Mark Kozelek already feels his mid-twenties pounding at the door "like a friend you don’t want to see." Add 15 years to that anxiety and you have "39," a tour de force of spleen venting at nature's clock.

"Half my life I’ve been here/ Half my life in flames/ Using all I ever had/ To keep the fire ablaze," Smith confesses, his wail draining to a moan. He was actually grappling with two half-lives, as by that point leading the Cure had been Smith’s focus since the late 1970s when Sussex punk upstarts the Easy Cure trimmed their name and their ranks from four to three imaginary boys. Half of his existence had been consumed by pushing his ragtag trio from the post-punk sideline into the mainstream, all while keeping the makeup smeared on and the drama dialed up to eleven.

Bloodflowers' preoccupation with the calendar doesn’t only manifest in pale fire. Softer reflections stitch it all together, summarized by a passage from Alfred Lord Tennyson's "The Princess" that appears in the liner notes, which reads like the Cure’s "About Me" page:

...I know not what they mean

Tears from the depth of some divine despair

Rise in the heart, and gather to the eyes

In looking on the happy Autumn fields

And thinking of the days that are no more

"I...knew the album was going to be nostalgic and wistful, because I was writing words that summed up how I was feeling heading towards becoming a 40-year-old," Smith told Guitar Player in 2000. "That set the tone for what I wanted to do musically, but I wasn't sure how I was going to achieve it." To Smith’s credit, the opening "Out Of This World" does it well. Fading into an album with diffuse percussion and an acoustic strum was more than a little out of character for the Cure. All of the guitar parts on "Out Of This World" sigh, including the dripping Disintegration-style solo.

Smith finally walks in after two minutes, sounding like he’s been awake for two days straight. His voice cracks and croaks with sweet but weary sentiment. "When we look back at it all as I know we will/ You and me, wide eyed/ I wonder will we really remember/ How it feels to be this alive?" There is a transitory passion at the heart of "Out Of This World" between two partners or lovers who "always have to go back to real lives" where they belong. Smith could be memorializing the end of an imagined fling, or perhaps he's pulling out some thread of experience from what the Village Voice's review of the album referred to as his "famously wonderful marriage" to his teenage sweetheart. Lyrically and musically, like much of Bloodflowers, "Out Of This World" is loosely formed and open-ended.

In the Cure fan vocabulary of the 1990s, the "trilogy" in the band’s catalog was that of their second, third and fourth studio LPs. Seventeen Seconds, Faith, and Pornography arrived almost like clockwork each spring between 1980 and 1982. Post-punk pulled apart, each stark and sullen document grew ever more bleak until something had to break. In those days the Cure were entrenched in the goth realm; Smith even occasionally served as a touring guitarist for Siouxsie And The Banshees. A decade later, when legions of listeners were humming along with "Friday I’m In Love," those reputation-making records had receded into a former phase -- even though Smith's image and fashion sense would (and still does) hold its ground -- and Seventeen Seconds, Faith, and Pornography came to be casually referred to at least by some as the "goth trilogy."

Somewhere amidst the genesis of Bloodflowers, however, Smith got it in his head that there was a different trilogy in his catalog which was less bound by chronological order, consisting of Pornography, Disintegration from 1989, and his latest. This notion was cemented with the release of the Trilogy DVD in 2003, which captured concert performances from the previous year of the three albums. Does Smith’s insistence on a bond between Cure albums separated not just by time but by distinct points in the band’s creative and commercial timeline really pan out?

Pornography is a notoriously despairing disc. Its first words are "It doesn’t matter if we all die." Its last, "I must fight this sickness/ Find a cure," are hopeful only in comparison to the torrent of melodrama that spills out before. Disintegration, which came seven years and a huge raise in the Cure’s profile later, has a back half that lyrically can compete with the darkest corners of the band's catalog. That Disintegration simply can't match the corrosion and anger of Pornography is not a shortcoming; Smith was very much on a roll coming up with what remain some of his most mature and finely constructed singles such as "Lovesong" and "Lullaby."

Though the latter has a lot more hooks and mass appeal than the former (no less than Kyle from South Park once declared that "Disintegration is the best album ever!"), the symbolic connection between the roles that Pornography and Disintegration play in the Cure's body of work isn't just in Smith's imagination. Pornography is a leaden capstone to the band’s lean punk-borne years, while Disintegration is an equally but differently weighted apogee of their '80s reinvention and ascendance. Their moods are not incompatible, and, well, some of their songs do go on for a bit.

The songs on Bloodflowers also tend to be stretched out and sorrow-hued, and there is a tie in that this record marked the arrival of Smith’s forties in the way that Disintegration did his thirties. Otherwise, the album doesn’t really achieve the same sense of closure on an era. The '90s were an up-and-down decade for the Cure. The (relatively) lighter-hearted Wish, released in 1992, was huge, but the following Wild Mood Swings -- which is not quite as erratic as the title suggests, and a little better than you probably remember it -- was the first Cure album not to sell more copies than the one before it. Some wondered if part of the problem was that Smith sounded perilously close to being happy at times.

Bloodflowers shuns the kind of pop gratification that Smith occasionally tossed up from "Mint Car" back to "The Love Cats," and instead plays a hand heavy with vibe. If some of the tracks feel almost interchangeable, that is very much by design. “With this album,” Smith told Guitar Player, "I did a bit of a Brian Eno number -- I was imposing structure. I imposed what keys I could write in, what tempos I could have, and the number of times I could repeat certain phrases.... One good thing about working in complementary keys and tempos is that I could swap parts from song to song."

This was the first Cure album on which Smith had improvised his guitar solos. He originally wanted to play every one of the guitars he owned on it, but he abandoned the idea after realizing he had more than 50, and decided to stick mostly to two. It seems Smith wanted to make a career summation that was both off-the-cuff and cumulative. "I accept now that the Cure have a sound, and this album is the sound of the Cure," he said when it came out. "The difference is, now I like that idea."

Not everyone was convinced that Bloodflowers was a definitive statement, and critics were divided on what worked and what did not. Uncut called "Out Of This World" a "crisply layered, quietly hypnotic" gem, and the middle pair of "The Last Day Of Summer" and "There Is No If…" are deemed to be "cut from equally classy cloth." On the other hand there's "Watching Me Fall," a stormy saga of self-remove, which "takes 11 turgid minutes to pointlessly regurgitate the Mission’s entire back catalogue." Coming from the opposite direction, Rolling Stone praised the "lyrical fatalism" and "tense cymbal work" of "Watching Me Fall," while dismissing "Out Of This World" as "passionless and without direction," and declaring, "The album's soft, chewy center, five songs' worth, never varies in rhythm or pace."

"Does nihilism still play when you’re 40?" asked the Hollywood Reporter, oblivious to how Bloodflowers is desperate not to dismiss but to find meaning in life, in blood flow. Even Smith’s musing on how "...the world is neither just nor unjust/ It's just us trying to feel that there's some sense in it" in "Where The Birds Always Sing" is not merely a dour perspective but a time-revealed truth. Such assessments in the press were content to cruise on old Cure stereotypes. "If life really begins at 40," began a concert review by writer Keith Cameron in the Guardian in early 2000, "then pity Robert Smith, a man who has spent more than 20 years ruminating on the sheer hopelessness of existence."

The threat of a final curtain proved to be premature, and though Bloodflowers didn't reverse the trend of declining sales, a younger generation of admirers were catching up and forming bands of their own. In 2004, the Cure felt reinvigorated enough to round up a small festival’s worth of acolytes including the Rapture, Interpol and Mogwai (the latter’s Young Team had inspired Smith to make Bloodflowers more guitar-driven) to go on the Curiosa tour with them that summer. It was an ideal lineup for some fans (it certainly was for this one, except that the Gorge Amphitheater date was cancelled at the last minute), but a less simpatico alignment led to the band’s other big event that summer, the release of a new self-titled album.

If the fact that producer Ross Robinson, one of the men most responsible for nu metal, was put in charge of making a Cure album doesn’t convince you that too many drugs and/or bad decisions were going around in the early '00s, then nothing will. "The resulting sessions were not easy," observed Music Week in late 2004. "In the early stages of the relationship, as Robinson pushed them to achieve increasingly intense performances, there were tears and threats of violence but, as the sessions forged ahead, it was realised that Robinson's obsessive quest for heightened emotion was resulting in the best album they had made for years."

Even if in the moment the choice made sense to those involved, that Robinson was allowed to use his infamous studio bully methods on one of rock music's patron saints of sensitive souls is in hindsight blasphemy. Music writer Ian Gittins highlights the absurdity of it all in his 2018 book, The Cure: A Perfect Dream, where he notes that "Robinson had a habit of standing in front of [Smith] as he recorded his vocals, barking at him: 'Come on! Make me cry!'" The positive spin put on this collaboration back then hasn’t aged well, and neither really has The Cure, nor the marginally improved 4:13 Dream from 2008. Those last two studio albums churn with a malcontent disposition, but shafts of the old Cure light too rarely poke through.

The old one-dimensional view of Smith and his band that had been recycled in appraising Bloodflowers were now regarded as a virtue. Awash in testimonials to their influence on big-name nu-metallers and hip post-punk revivers alike, the Cure sounded less like they were playing for themselves and more like they were catering to the tastes of the times. Yet it is hard to blame Smith for courting a receptive audience, even if they were embracing certain heightened emotional and stylistic aspects of the band and not the whole picture.

Compared to The Cure and 4:13 Dream, Bloodflowers does feel like the last fully honest Cure album. Cameron was on point when he wrote, "The new songs don't wield the consumptive power of yore -- Smith would probably be dead if they did -- but at least they sound authentic, riven with the same existential certainties that define the band's best work." "The passions that Smith spills into his bon mots seem heartfelt," agrees Gittins, while also conceding the songs aren’t as catchy as the singles of yore. Bloodflowers isn’t seeking out new friends, it wants to have a meaningful conversation with old ones, like you do when your forties inch closer.

Last August, the Cure played a huge field in a Glasgow park. Remarkably, it was their first show in Scotland since 1992. After a nearly three-hour set of career highlights, his bandmates having already made their exit, the 60-year-old Smith lingered on the stage, walking back and forth nearly bouncing on his heels, soaking in the adulation. His exuberant last words to the thousands gathered before him were "See you again!" Smith in that moment might have forgotten how long it had taken him to get back there, but he may also have been more keenly aware than ever of time’s passing.