"I wonder if Chance the Rapper do his own laundry." That's Rory Ferreira, the man formerly known as Milo, about halfway through his song "Laundry." Before even pausing to take a breath, he answers his own question with a question: "Who cares?" It's one stray strand of thought, one that Ferreira dismisses as soon as it flits across his consciousness.

"Laundry" is nothing but thoughts like those -- a collection of the idle, meditative synapse-firings that might happen when you're dealing with a big pile of still-warm clothes: "You know, the devil is a liar/ So pants don't go in the dryer." The music is a light, pleasant boom-bap bubble -- a sampled drum shuffle, a noodling electric piano, the scratched-in voice of Masta Ace bragging about being hot like clothes in the dryer. "Laundry" is a playful song, a low-stakes trip into one guy's overactive brain. It's Rory Ferreira at his most comfortable, which means it's still the most adventurous rap song you'll hear all day.

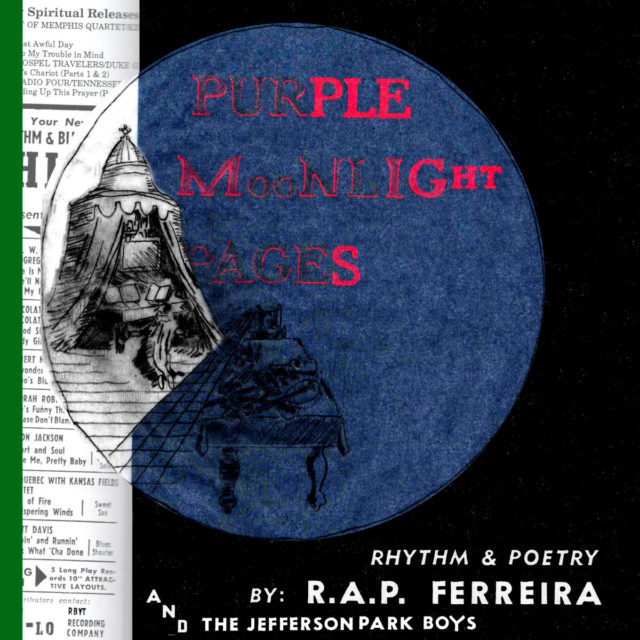

Up until two years ago, Rory Ferreira was Milo, an underground rap staple who'd been making music since the beginning of the last decade, kicking expansively dense thought-branches, often over his own beats. Like the aforementioned Chance The Rapper, Ferreira came from Chicago. Unlike Chance, Ferreira spent his youth moving around -- Maine, Wisconsin, a sojourn in the Los Angeles underground rap scene. In 2018, Ferreira announced that Milo -- a name he may have originally chosen in honor of The Phantom Tollbooth -- was "officially finished." He'd undertaken a beautifully quixotic journey, moving with his family to the tiny town of Biddeford, Maine and opening a rap record store called Soulfolks. Eventually, he announced that his new alter-ego was R.A.P. Ferreira. Purple Moonlight Pages is his first album under that name.

Ferreira has always been as much producer as rapper. But on Purple Moonlight Pages, the production is credited to the Jefferson Park Boys -- the close-collaborator trio of Kenny Segal, Mike Parvizi, and Mr. Carmack. Musically, Purple Moonlight Pages drifts even further left than the languid, broken post-boom-bap that Ferreira had been making toward the end of the Milo project. Here, the beats are full of live instrumentation: murmuring bass, idle guitar flutters, occasional bursts of horn. Jazz is an obvious inspiration; the album ends with a brief variation on the 1969 Pharaoh Sanders piece "The Creator Has A Master Plan." And Milo delivers most of his lines in his own meter, taking on some of the faux-preacher cadences that I tend to associate more with slam poetry than with straight-up rap. The songs unfurl on their own schedule. They're never too long, but you're also never quite sure which direction they'll twist in next.

Lyrically, much of Purple Moonlight Pages seems to be built around the idea of dropping out of the rap rat race. I say "seems to" because Ferreira has always been an intimidatingly dense and allusive writer, one who demands annotation. When he idly offers up something resembling advice -- "Professional rappers often only heard postmortem; perhaps try trade school" -- it's hard to say whether he's flexing on wack competition or making some larger philosophical point about the futility of certain dreams. It's clear enough, though, that Ferreira's not a fan of playing the game: "Preaching the rhyming word is absurd as pledging allegiance before reading terms of service agreement," "Twisted world where artists bend backwards for benefactors/ And victims are to be blamed as bad actors."

Ferreira is almost rapturous when he zones out on small-stakes domestic delights, and he often does that at the expense of active participation in the rap economy: "Fuck wealth and the hype machine/ Rather have health and a icy spring, or electrician training/ I can hear a rapper hesitating/ But that won’t pay his car note, will it?" To the extent that the middle-class avant-rap struggle is a theme on Purple Moonlight Pages, Ferreira's longtime collaborator Open Mike Eagle, one of the album's two guests, might state it the most plainly: "Rudderless victim history/ I should’ve chose a gig with income consistently."

For his part, Ferreira seems less interested in asserting those themes, more interested in playing games with language. He expounds on gas-station bathroom graffiti, or on being kicked out of Wegman's for rapping. He speaks about being "in Tim Horton’s, dressed like a Transformer, talking about Jacob Lawrence portraits." His one-liners are the kinds of things you can pick apart all day: "My mind’s favorite yoga pose is pulling okey-dokes," "This beat sound like a long walk to the dumpster, funk like nostrils of muenster," "Then I played pinball with Zev Love X." He doesn't even say MF DOOM. He says Zev Love X.

As ever, Ferreira loves the sound of his own voice, the taste of words in his mouth. "It's all our turf," he says, echoing the martyred gang messiah from the opening of The Warriors, letting the words roll around. Toward the end of the album, Ferreira lets loose with something like a mission statement: "I desperately need to be understood. I desperately need understanding." Ferreira doesn't always make that understanding easy; Purple Mountain Pages is one of the richer, more abstract, more discursive rap albums that I've heard in recent memory. But if he made it easier, then we wouldn't really understand him, would we?

Purple Moonlight Pages is out 3/6 on Ferreira's own Ruby Yacht label.

Other notable albums out this week:

• Stephen Malkmus’ synthy excursion Traditional Techniques.

• Worriers’ tuneful punk rocker You Or Someone You Know.

• U.S. Girls’ thoughtful, melancholy pop record Heavy Light.

• Bacchae’s nervy punk debut Pleasure Vision.

• Swamp Dogg’s blearily, craggily soulful Sorry You Couldn’t Make It

• Snarls’ hooky DIY debut Burst.

• Disq’s rumpled indie rocker Collector.

• Phantogram’s polished festival-popper Ceremony.

• Cornershop’s psychedelic return England Is A Garden.

• THICK’s personal, political punk debut 5 Years Behind.

• My Dying Bride’s goth-metal exorcism The Ghost Of Orion.

• Caroline Rose’s cinematically inspired Superstar.

• Addy’s blurry bedroom-pop debut Eclipse.

• Riz Ahmed’s UK lament The Long Goodbye.

• Summer Camp’s experimental hardcore debut Overjoyed In This World.

• Esmé Patterson’s dreamy, synthy There Will Come Soft Rains.

• Pantha Du Prince’s forest-music project Conference Of Trees.

• The self-titled collaboration from Mark Kozelek with Ben Boye and Jim White.

• P.E. (not Public Enemy)’s art-punk debut Person.

• Iji’s self-titled bedroom-popper.

• Bankroll Fresh’ posthumous LP In Bank We Trust.

• CocoRosie’s art-pop comeback Put The Shine On.

• Body Count’s reliably tough Carnivore.

• NCT 127’s futuristic K-popper Neo Zone.

• Mandy Moore’s tasteful comeback Silver Landings.

• The not-actually-going-away Moby’s charity album All Visible Objects.

• William Tyler’s score for the film First Cow.

• Anna Calvi’s reimagining collection Hunted

• Noel Gallagher’s High Flying Birds’ Blue Moon Rising EP.