Sometimes you can hear a band's hometown in every fiber of what they do. There's some kind of stylistic calling card, sounds or dispositions that tie them to a specific scene and city and time. There are themes or topics that they fixate on, stories that arise directly from their surroundings or upbringings. But then other times, you can't trace any of this. There's no surface evidence, but where a band comes from is still woven into their DNA, flowing into the music they make.

It's no small thing that Porridge Radio originated in the seaside English town of Brighton, partially for practical reasons. Brighton is a music town, home to Nick Cave and the label Bella Union and the rising-talent-discovery-festival the Great Escape, and a whole host of young and scrappy bands feeding off of each other. But it isn't a global hub in the same way as London or New York, rather a smaller place off to the side. You can still hop the train to London easy enough, but otherwise it allows you to exist at a remove and carve out your own path.

That's what Porridge Radio did: They came up in Brighton, and they spent a lot of time at the sea. That's what's in their DNA. Hours passed at the edge of town, the edge of their country, staring out into vast waters equal parts corrosive and cleansing. They could take comfort in the constant ebb and flow of waves rising and dissipating; they could wrangle with the unknowable chaos that lurked out there if you looked at it too closely, for too long. Porridge Radio's new album, Every Bad, might sound like a band from Brighton or from England at large in 2020; it might sound like a band from Philadelphia or the Midwest, too. What Every Bad really sounds like is the sea, churning then soothing, a constant battle between birth and destruction.

Porridge Radio leader Dana Margolin arrived at a lot of those same thoughts. "Swimming is a way to wash away all the shit," she said in our Band To Watch interview earlier this year. "You're on the edge of everything when you're at the beach." The same polarities captured her imagination, too, the sea being "terrifying... and overwhelming and also really calming and beautiful..." She might as well be describing Every Bad.

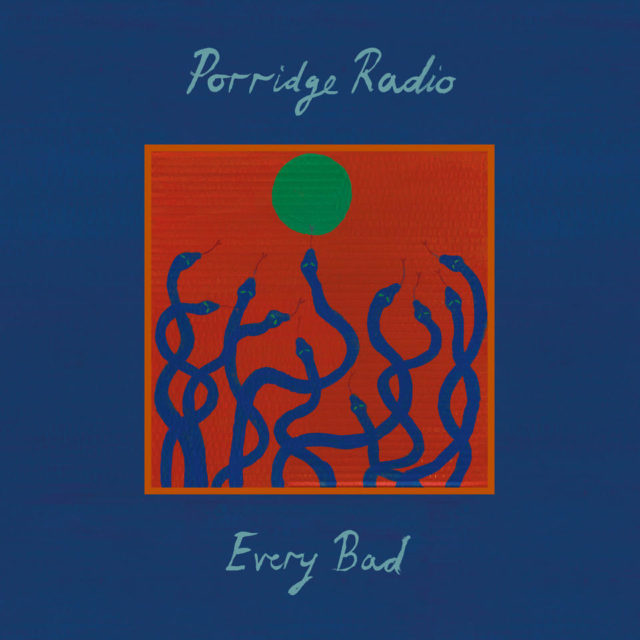

The band has been building up to their new album for almost a whole year. Three singles arrived spread out over 2019, before the official rollout kicked off in January. Along the way, they were signaling that this band had become something else. While Porridge Radio's 2016 debut Rice, Pasta And Other Fillers was promising, it was also something of a rough draft or a prologue. Every Bad is a level-up that feels like their proper introduction, a more fully-realized sound and a distinct voice coming into its own.

Across the album, Porridge Radio lean in a bunch of different directions -- straight-up indie, dream-pop, heaving '90s alt-rock, the moodier edges of Britpop. Each single released over the last year found Porridge Radio taking on a slightly new shape, but all of it was strung together by Margolin's weapons-grade vocal power and the muscular intensity of drummer Sam Yardley, keyboardist Georgie Stott, and bassist Maddie Ryall's performances. That's no different when you listen to Every Bad as a whole. Songs flow fluidly and the dramatic arcs of the album proceed gracefully, the entire thing an exercise in writhing angst turned to primal scream release.

Margolin conceived of Every Bad as "an unfinished sentence," its title a capacious signifier of the strife catalogued across the album but also an invitation for the listener to find solace for whatever their own struggles are. Musically speaking, however, there is nothing out-of-focus about Every Bad. Moving beyond their more lo-fi origins, Porridge Radio have crafted an ambitious, tempestuous album with a grand scope that blows out personal demons into universal trials. Opener "Born Confused" sketches out the approach of many songs on Every Bad: a simmering opening quickly unfolds into waves of emotions, cresting higher each time until finally crashing down and fading out.

While every sound on the album is perfectly executed, the songs themselves are allowed to rise and fall, to push against their confines and break down -- like when the off-kilter groove of "Don't Ask Me Twice" is suddenly ruptured by a seething punk interlude. "Sweet" wastes little time in introducing its violent dynamic shifts, almost forebodingly calm verses lacerated by sudden eruptions of disorted guitar. "Long" builds patiently until boiling over, while "Circling" swirls around itself until reaching a similarly dramatic conclusion. The band pulls back ever so slightly for the wounded reflections of "Nephews" and "Pop Song," but it's the ease and infectiousness of "Give/Take" that probably offers the clearest reprieve from a musical standpoint. Mostly, though, these songs twist and roil; they are not so much unfinished sentences as conversations that furiously spin in circles and collapse in on themselves.

The latter quality mirrors the emotional landscape of Every Bad and Margolin's lyrical approach throughout. Many of the songs deal with distance from or conflict with another person, and a person trying to work themselves out within that dynamic. "I'm bored to death let's argue," Margolin sings at the album's opening; by the end of that same song, "Born Confused," she goes from matter-of-fact to a torn wail as she repeats, "Thank you for leaving me/ Thank you for making me happy." In "Long," it's the emphasis on "You're wasting my time" turning to "I'm wasting my life" and "I'm wasting your time/ I'm wasting everything." In "Give/Take," it's "Don't you know that I want more" answered by a blasé insistence of "I want want want want want want want want want you."

Many of the songs sound like they're grappling with a romantic relationship, while "Sweet" has recurring images of Margolin's mother. (It opens with her calling Margolin a nervous wreck.) At the same time, much of the album could easily be seen as a person at war with themselves, trying to get better or just trying to figure themselves out. Margolin's spoken about her liberal use of litanies, repeating certain lyrical variations or phrases almost ad nauseam, again and again until she purges something within herself -- or sometimes, it seems, until she can believe in them more wholly. Many of these mantras speak to personal conflict, the desperate attempt to reckon with your own thoughts and feelings: "I don't know what I want/ But I know what I want," she sings on "Don't Ask Me Twice." It all portrays the condition of being young and trying to locate something stable inside, some clarity about your own identity and dreams.

There are plenty of climactic moments across Every Bad, with almost every song building to some apex or another. But the album's peak arrives with "Lilac," the song that immediately demanded people's attention when Porridge Radio released it last winter. "Lilac" is, simply, a stunning composition -- a slow-burn, atmospheric track, one of the album's gentler and more genuinely pretty passages eventually giving way to the truest catharsis to be found on Every Bad.

At first, it covers similar ground to the rest of the album's material via the reigning mantras "I'm stuck" and "I can never seem to find it." But then the song blooms. From the textural first half -- with violins distantly keening like birds above the beach -- it appears like "Lilac" will turn into a storm, guitars and strings layering into a claustrophobic haze of noise. Then, Margolin starts singing: "I don't want to get bitter/ I want us to get better/ I want us to be kinder to ourselves and to each other." The music begins to swell, leaving you suspended in the center of an explosion as Margolin escalates from hushed, not-quite-sure readings of the line to screaming it into existence. Once more, Margolin modulates the meaning of a lyric through singing it over and over, reworking the structures of the words; this time, it doesn't just burn away the anguish, but results in a rallying cry. On an album that wrestles with so much darkness, "Lilac" is the reward, for Porridge Radio and for those listening. It's a promise that all this could lead to something else, that you can grow.

Fittingly for an album inspired by the unending currents of the sea, an album featuring a constant succession of litanies roared into the void, and an album partially left open-ended by design, Every Bad doesn't necessarily conclude in a more contented place than it begins. Several more tracks follow the semi-resolution of "Lilac," all leading to the mesmerizing but haunting "Homecoming Song." Rather than a sense of peace in said homecoming, the album concludes with one more refrain: This time, as she drifts out on one of the album's more aqueous arrangements, Margolin proclaims, "There's nothing inside."

But that's the beauty of Every Bad. "Homecoming Song" is just one more ellipsis, not a moment of defeat but perhaps rather a moment of letting that feeling go by voicing it -- repeating the words until they lose all meaning and become harmless. You have to locate the moments of change and hope throughout the album, but they are there. In a sense, Every Bad captures and communicates one consistent aspect of our lives in 2020, that feeling of wanting to scream at all of your surroundings all of the time. But it can also leave you with the sense that if you follow those unfinished sentences into whatever unforeseen direction they lead, that it might not always be this way.

Every Bad is out 3/13 via Secretly Canadian. Pre-order it here.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=U3BrQzmBF1w[/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=3Pbfa4TW5fA[/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=CIRelXjAY7s[/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=27BvZLSzaz8[/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=Ygg2G2ehMFU[/videoembed]

Other albums of note out this week:

• Four Tet's highly anticipated Sixteen Oceans.

• JFDR's gorgeous, crystalline sophomore outing New Dreams.

• The Flaming Lips x Deap Valley team-up Deap Lips.

• Ultraísta's reunited sophomore effort, Sister.

• Yumi Zouma's pristine, dreamy Truth Or Consequences.

• Code Orange's brooding, adventurous Underneath.

• The Boomtown Rats' first album in 36 years, Citizens Of Boomtown.

• Porches' latest collection, Ricky Music.

• Vundabar's jittery and melodic Either Light.

• Dogleg's blistering, video-game-indebted Melee.

• Hilary Woods' gripping, visceral Birthmarks

• Niall Horan's second solo endeavor, Heartbreak Weather.

• Blanck Mass' first true foray into film music, Calm With Horses - Original Score.

• Bartees Strange's EP of National covers, Say Goodbye To Pretty Boy.

• Lily Konigsberg's It’s Just Like All The Clouds EP.