Doves was always a misnomer. As the story goes, the band rose from literal ashes. In 1996, the trio behind Doves -- Jimi Goodwin, and twin brothers Jez and Andy Williams -- lost their studio to a fire, including all of their instruments and any recordings they had been working on. What could've been a moment of catastrophic defeat instead turned to a slow rebirth, as the three set about finding themselves a new identity, rechristening themselves not Phoenix but Doves. (Given that Thomas Mars and friends were rising out of Paris at the same time, this was probably for the best.)

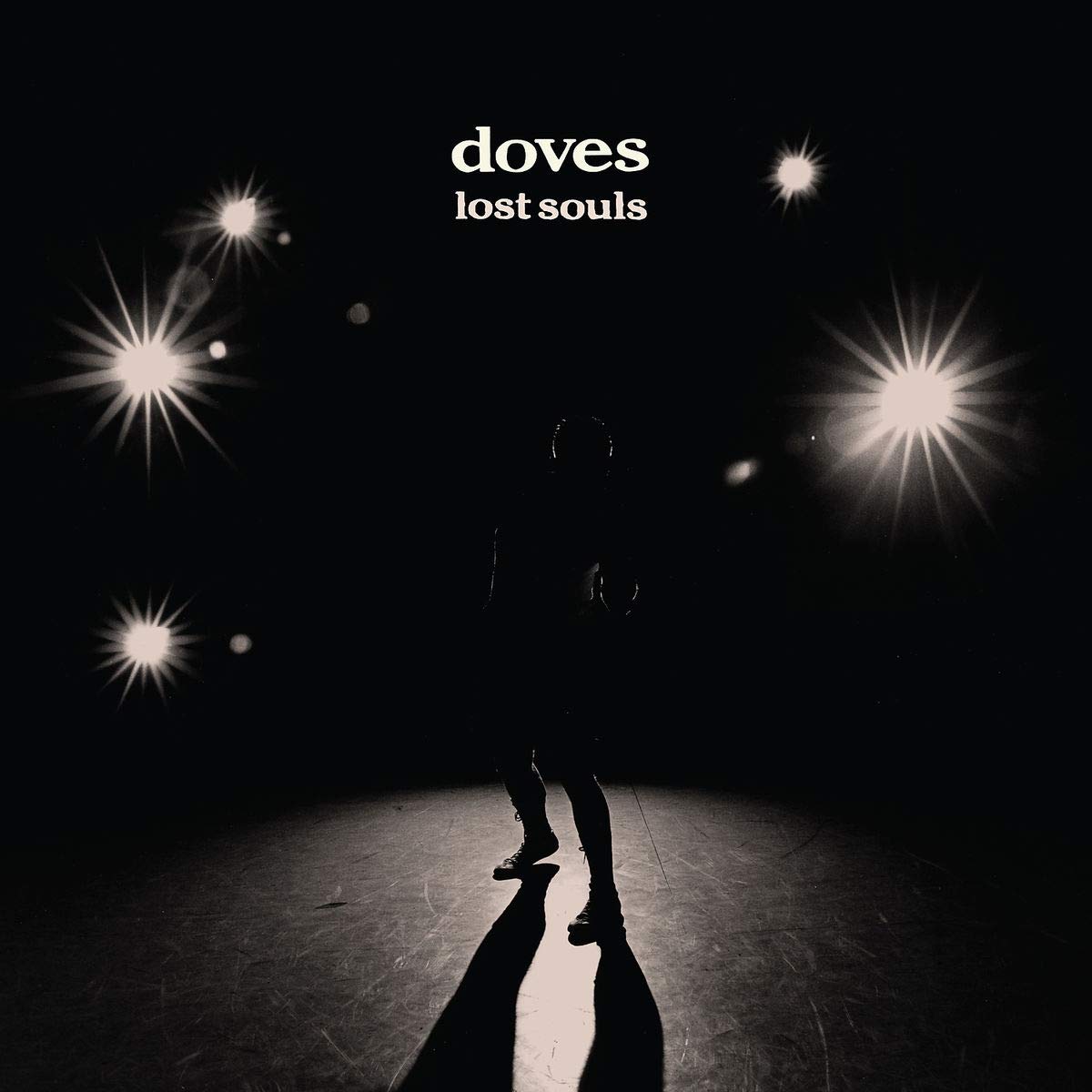

When their debut album Lost Souls arrived, 20 years ago today, the resurrection was complete. The history of Goodwin and the Williams brothers goes quite a bit further back than that though. As teenagers in the greater Manchester area, they met and bonded over artists from their hometown like Joy Division and the Smiths. They frequented the dancefloor at the fabled Hacienda. That prompted them to start a house band themselves, Sub Sub, which seemed poised for success when their 1993 single "Ain't No Love (Ain't No Use)" hit #3 on the UK Singles Chart.

Instead, the band's fortunes petered out from there, with an album that failed to catch on in the same way. Their timing was off -- they were a bit late for Madchester, but didn't fit into the Britpop craze that was engulfing their homeland. Though the fire provides a neat real-life metaphor for the end of Sub Sub and the beginning of Doves, in truth the trio had already begun reconceptualizing who they wanted to be as a band. But they were soon given a fresh start by way of the cosmos forcing their hands, and they crafted an entirely new sound for themselves -- one that, this time, wouldn't just capture a moment in British music, but would help define it.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

By the time Doves were crystallizing their vision in the late '90s, Britpop was collapsing in on itself. All the primary artists were breaking up, or fraying, or making sprawling and difficult albums that seemed to signal the end of an era, paralleling the way grunge was fading and mutating over in America. While each country would, again, have a similar experience in the '00s -- the retro-rock revival in America mirrored by the brattier, cartoonish Britpop, punk, and mod descendents the likes of Libertines, Kasabian, Kaiser Chiefs -- and while guitar music still holds a bit more mainstream cache across the pond than it does here, the end of Britpop and grunge respectively symbolized not only the end of a century, but the end of, in some senses, the growth and dominance of rock music as an idiom.

Doves were part of the in-between, they and a handful of like-minded bands -- including Coldplay, Elbow, and Travis -- arriving not so much in the wake of Britpop, but in the shadow cast by Radiohead, chasing a mistier and more atmospheric aesthetic. It was a transitional time between two distinct scenes, and the bands that began here often managed to exist in some grey area: both euphoric and melancholic, both downtrodden and anthemic. As it turns out, Doves were a band well-equipped to depict liminal spaces. They came into their own amidst the destruction of their old selves, and the destruction of their immediate predecessors, but Lost Souls doesn't exactly sound like a new dawn. It's an album that takes place in the middle of death and life, the hazy waning hours of one long night just before it cedes to the clarity of morning.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Opening the album with the semi-instrumental "Firesuite" made the resurrection literal. Figuratively if not literally an overture, the song was a curtain rising on the official beginning of Doves. "Firesuite," too, was something of a misnomer. Far from something born in flames, it instead sets the aqueous tone of Lost Souls. Sometimes, though rarely, a pop band's instrumental efforts aren't filler or segues, but pivotal to their album or even their identity. “Firesuite” was that way for Doves,with disembodied, wordless vocals calling out like a silhouette starting to come into focus out of the ether. For much of Lost Souls, Doves didn't sound like they were sifting through burnt ruins, but rather wading into murky waters.

Across the rest of the album, Doves proved they had a fully-realized new style, but also ventured off in a lot of different directions. Right after "Firesuite" was the eerie lounge-pop inversion of "Here It Comes," one of the album's calling cards and yet a total outlier. That and the infectious rocker "Catch The Sun" were the most direct compositions; otherwise, the band wrung impressionistic passages into elusive, evocative songs. "Break Me Gently" and "Rise" were submerged, flickering with vivid watercolor guitars and ghostly vocals. Elsewhere, the band leaned into the whole "post-Britpop" vibe with stuff like "The Man Who Told Everything." With a lachrymose string figure and a mournful melody, it sounds halfway to a would-be end credits anthem that was forgotten in the rain.

Then there were the moments when the band gave themselves over to something entirely otherworldly, where they tapped into a mystic vein and let it overflow. It wouldn't be accurate to call Lost Souls a psychedelic album, exactly -- and certainly not in the '60s-indebted sense of much British music immediately before or after it -- but there is a moodily trippy quality to much of it. At the time, this seemed to be attributed to the trio's dance music bona fides, the idea that there was some pulse or release endemic to their songwriting that had now been translated into the rock format. Thetwin epics of “The Cedar Room” and “Sea Song” were already foundational Doves songs, each having been the namesake of late '90s EPs leading up to their debut. But in this capacity, they also became the pillars on Lost Souls itself, the fully transporting sprawls that completed certain arcs within the album.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

“Sea Song” arrived early in the album, the crest of the opening stretch. It's gorgeous and propulsive, fittingly making you feel as if you are in the center of a storm, rippling and churning guitars like waves crashing over you. That and “The Cedar Room” both remain contenders for Doves' best song, even after all these years; each is crucial to the album. "The Cedar Room" is functionally the climax, the big shimmering conclusion to the story of Lost Souls. There's a hypnotic quality to it, somehow sustaining its drama for eight minutes without really changing direction much. Chronicling a breakup, it once more finds Doves in the process of ends and beginnings, but despite the loss at its center, its mantra-like repetition makes it feel like one final, actual catharsis -- lost souls settling into some long-awaited realization.

It's followed just by the reset of "Reprise," and then "A House," an epilogue by way of a prologue out of chronological order. The first time Lost Souls actually sounds like embers drifting through the air, "A House" sits at the end like a worn ellipsis, surveying what has just been built up by one last acknowledgement of the damage that had to happen first in order to get there.

When it came out, Lost Souls was occasionally written about through the lens of Goodwin and the Williams' backstory -- listless club kids growing up and starting to grapple with adulthood. The album does have a sense of weight and maturity. Though reinvigorated creatively, its themes are all of searching and wandering. Though often mesmerizing sonically, you can hear the human struggle that went into it, in a very practical way.

Goodwin never set out to be a lead vocalist; the band originally sought a frontman before deciding they liked his voice. Along the way, you can hear every crack and grain in his voice, the wear and tear of every night gone on too long. You can hear every nascent wrinkle in their faces, the sound of years ticked away and new discovery even as age creeps in. In a sense Lost Souls is the comedown to the comedown, a goodbye to their own youth but also a goodbye to the heady decade of Britpop. As much as there is something mournful running through the album, there's also an earnest grasp for beauty; every now and then, the band's fingers graze the edge of transcendence.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Just under an hour long and musically dense, Lost Souls is still immersive, and could've been too much to get through if it came from someone else. But Doves were fueled with the kind of creativity that comes with discovering the voice you thought you had wasn't your real voice at all. And people heard that in Lost Souls. The band was well-regarded by critics, and Lost Souls was shortlisted for the Mercury Prize. While not tossing out hit singles, it looked like Doves could strike a balance between everyman, far-seeing, and expansive that might make them one of the next big names in British rock music.

That wasn't quite how it went. After Lost Souls came The Last Broadcast, which felt like a companion piece that was just a bit brighter, looking towards a starlit sky more so than to the fog in our own heads. After that, Some Cities and Kingdom Of Rust presented a more down-to-earth Doves, with more tangible and straightforward songwriting. The band's best work, while frontloaded on the first two albums, is still spread out through their career, with some of their signature tracks appearing later. But some of the magic and mystery wasn't there anymore on the latter-day albums.

Lost Souls isn't the sound of a place you want to remain in forever, and yet two decades later its shadows still have new things to reveal. You can't necessarily say that for the other Doves albums. After touring Kingdom Of Rust, Doves went on hiatus for most of the '10s, reuniting last year and offering lots of hints of new Doves music to come. Who knows what it'll sound like. Maybe, once more, a half-death will result in something striking from Goodwin and the Williams brothers.

It's hard to say exactly whether Doves are an under-appreciated band. They have a devoted, cultish fanbase, and have had occasional forays into the mainstream -- “There Goes The Fear” in particular is the kind of song that occasionally pops up in public or in a movie. When they went on hiatus, they left behind a rich but not-completely-perfect catalog. And when it comes down to it, Doves put their stamp on a micro-genre and a fleeting era.

Just like their origins in the Sub Sub days, they were never quite a part of the bigger story. But with Lost Souls, they released one of the few classics to come out of that little turn-of-the-millennium chapter in British music. Even two decades later, as the band and its listeners have continued to get older, even knowing how the story went from here, Lost Souls can still take you back to that enigmatic moment of transformation. The further outside it drifts from the band's personal narrative or their surrounding context, the more transfixing it becomes, the kind of album that shifts in and out of focus and invites you to keep looking deeper and deeper.