Steven Ellison hadn't quite gotten to outer space yet, but he'd come close. With his first two Flying Lotus releases, 2006's 1983 and 2008's Los Angeles, he had already begun to build a reputation for himself as a Dilla disciple making his own brand of woozy, psychedelic music that combined hip-hop beats and electronic textures. People had already celebrated his adventurousness, his out-there take on beatmaking. And, sure enough, those first two Flying Lotus albums were dense head trips, bleary and nocturnal but sounding like something you hadn't quite heard before. Then, when Cosmogramma arrived 10 years ago this week, Ellison broke through the atmosphere entirely.

Or maybe he was going further inside, not towards the sky but deeper into the layers of his own mind and being, trying to read between the lines of the tangible world. The fact that Ellison is the nephew of Alice Coltrane was a huge part of his biography during the years when Flying Lotus was garnering more and more attention. It wasn't just a hooky detail to sell a new artist. Coltrane had been a crucial influence on Ellison as he grew up, not strictly as a musician but maybe even more so as a person. She helped to shape the way he perceived the world.

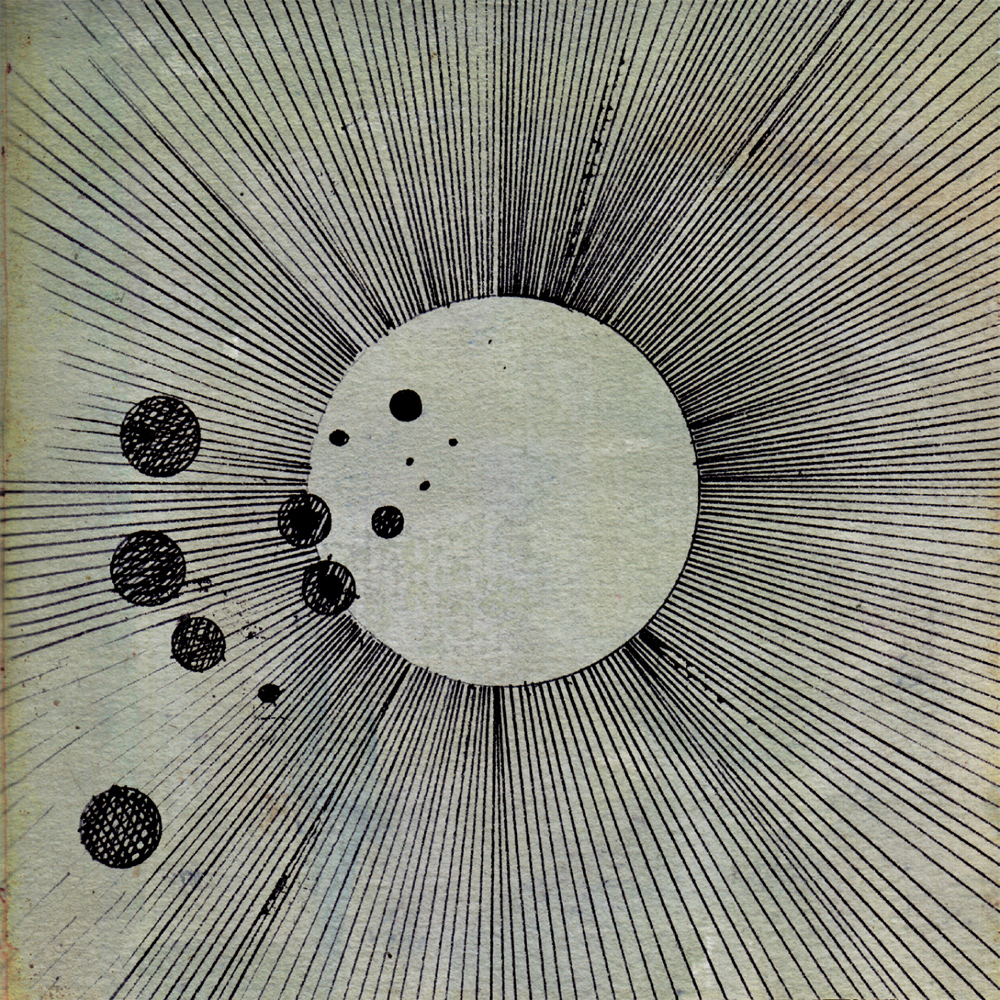

Between 2007 and 2008, both Coltrane and Ellison's mother passed away, and their loss is woven into Cosmogramma -- in its searching, enigmatic currents, but also in every fiber of its music. Ellison took the name from a devotional speech his aunt had given. In 2010, he told the Quietus that the term had "haunted" him -- though he initially misheard it as "cosmic drama" and later figured out it was this other word, one that alluded to "a map of the universe, between heaven and hell." It was, seemingly, one of those times when stumbling on a mysterious concept doesn't just unlock new avenues but illuminates what was already going on in your head.

There was a sense that Ellison had finally come into his own, working off inspiration from his family and artistic heroes to realize a sound that, by his own admission, he had only previously dreamt of. It was still drawing from recognizable histories, but sounded like someone wrangling music from the ether. Ellison had finally got to where he was going, and in turn there was a fervent, fascinated response to Cosmogramma. Ellison had arrived, and he'd done so by departing into a genuinely new realm of his own making.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=Xx82xI_ZheQ[/videoembed]

On a more practical level, Cosmogramma was the kind of kaleidoscopic genre free-for-all that also further honed Ellison's penchant for zone-out ear candy. If you were a stoned college kid losing yourself in the same video games and cartoons Ellison loved, or the kind of internet music nerd who obsessed over all the forms and references Ellison was imploding and combining, Cosmogramma was your soundtrack during those days. It was open-ended; oddly often characterized as challenging upon its release, it also always seemed like the kind of album in which you could more or less choose your own adventure, whether you wanted a sort of calming zen or a fantastic voyage alongside Ellison.

While working off a template primarily rooted in jazz, rap, and electronic meant that Ellison was already tapping into long traditions of structural exploration and production ingenuity, there was also something distinctly 21st century about what he was doing. There was so much going on here -- the boundary-pushing jazz of his family and artists like Sun Ra, the glitchy apocalypse electronica of IDM, video game music, a self-proclaimed "surrealist hip-hop." The biggest change this time around was the more noticeable jazz influence, the ghost of Ellison's lineage. But people still didn't know what to make of him. Reviews would place him in one world or another, and none of them were exactly right, yet none of them were exactly wrong.

As we exited the '00s and turned into the '10s, Flying Lotus felt like one of the musicians who was fully tapped into a new generation's experience -- the expansive but cluttered digital landscape, and all the loose ends and detritus we could collect and scramble there. Ellison's work sounded like a man trying to find balance in an over-stimulated world, an all-too-familiar experience for the listeners that found their way to Cosmogramma. And in turn, it was one of those albums that not only mirrored the way we were beginning to consume music and interact with media in general, but also served as a gateway drug, a rabbithole that just led to a broader network of rabbitholes.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=ygbb7UK1YDs[/videoembed]

Of course, the wonder of Cosmogramma was always in how Ellison wove all of this together. While the growth into jazzier musicality and incorporating more live instrumentation were the major transitions on Cosmogramma, it also marked the moment when Ellison had most successfully created an album-length statement, music that was most rewarding when experienced as one full piece. There were some discrete passages, like the gurgling video game music that opened the album as a kind of prologue. In a way those first few tracks almost feel like Ellison clearing his throat, trying a couple things out. Then the album takes off, one long interstellar arc.

Naturally, some songs still stood out. The trippy waves of "Computer Face // Pure Being," the shattered jazz transmission of "Arkestry," the trip-hop highway drift of "Zodiac Shit," "Mmmhmm" playing like a mantra uttered while coasting above the clouds, the infectious groove and dizzying build of "Do The Astral Plane" unfolding like an alternate universe club banger. Even in its quieter or more discomfiting stretches -- the simmering "Satelllliiiiiiiteee," Ravi Coltrane's sputtering, disembodied sax on "German Haircut" -- Cosmogramma came together into this twisting, turning whole, a vivid collision of ideas that still had a focus and destination.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=rE8g6etKAZw[/videoembed]

By the end, Ellison was going back to a version of home: "Drips // Auntie's Harp" and closer "Galaxy In Janaki" reference his aunt and mother, respectively. At the same time, they were the most transporting compositions, Ellison locating a truly otherworldly beauty. To this day they remain amongst some of his most powerful work. His moment of transcendence was a moment of becoming the person he was always meant to be.

In as many ways as Cosmogramma was an artistic and spiritual turning point, so too was it a functional turning point in the career of Flying Lotus. This was the true breakthrough for Ellison; he's been a fixture ever since, and his reach has only broadened over time. Cosmogramma also signaled his first collaborations with some important people. It was the first time he teamed up with a bassist named Thundercat; ever since, the two have been inextricable from each other's careers. That also connected Ellison to a bigger moment in LA music, this hybrid genre cross-section of jazz and rap that his Brainfeeder label has always been a part of.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=fZ82udFQ2uI[/videoembed]

And of course, Cosmogramma featured Thom Yorke on the chilly rumination "...And The World Laughs With You." Yorke would later take Flying Lotus on the road as an opener during his Eraser tour, which might've introduced Ellison to a whole other set of listeners again. At various points in the years following Cosmogramma, you could've imagined all kinds of new paths forward for Ellison: He could've brought his avant-garde beats fully into the rap world, an insurgent that would help remake this chapter in the style's history. He could have delved further into those Radiohead associations, become the sort of elusive electronic producer who occasionally crossed paths with the indie world.

Ellison didn't really become those things, but he also didn't really fall into any other patterns. People seem to sometimes take his work for granted now, when we're 10 or more years removed from his groundbreaking origins. But he's only continued to push forward: incorporating more instrumentation, constructing more album-length experiences, chasing further-out sounds, rapping himself, undertaking bizarre and gory film endeavors. He's still following his frenetic, shape-shifting muse. Again: He became himself with Cosmogramma, and he's stayed true to that self ever since.

Cosmogramma loomed over the last decade as a major album, but it still feels as if it exists on its own plane, somewhere over there. And as such, by its very nature, it still feels malleable, something you can turn over into different interpretations as needed. Cosmogramma is the ascendant space odyssey, but Cosmogramma is also the deep dive into the soul. Cosmogramma is a meditation on life and things beyond it, and it's an album-length reckoning with grief and absence. Cosmogramma is black and white static and hissing electronics, but it's also liquid strings and celestial voices, a mechanized grid of numbers that turns from digital code to the indecipherable language of the heavens. But, really, there's one thing that Cosmogramma remains after 10 years: Cosmogramma is always transforming, right before your eyes.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]